About a year ago, the Coalition of Communities of Color released a report referencing Portland State under the heading “The Latino Community in Multnomah County: An Unsettling Profile.” The following month there was a follow-up report on the Asian and Pacific Islander communities in the same county. Both reports were, as their titles suggested, “unsettling.”

$1 million worth of progress

About a year ago, the Coalition of Communities of Color released a report referencing Portland State under the heading “The Latino Community in Multnomah County: An Unsettling Profile.” The following month there was a follow-up report on the Asian and Pacific Islander communities in the same county. Both reports were, as their titles suggested, “unsettling.”

The focus of the research were the major inequities experienced by minorities in Portland, including in the area of education. It showed that 43.7 percent of Latinos haven’t graduated high school, compared to 6 percent of whites. Among Asians and Pacific Islanders, one in five don’t graduate high school.

The reports were downright bleak, and pointed to little progress being made in the “whitest city” in the U.S. They highlighted historic disparities in the levels of land ownership, employment and income levels between minorities and whites, suggesting that, as progressive as Portland counts itself, this is one area where it isn’t.

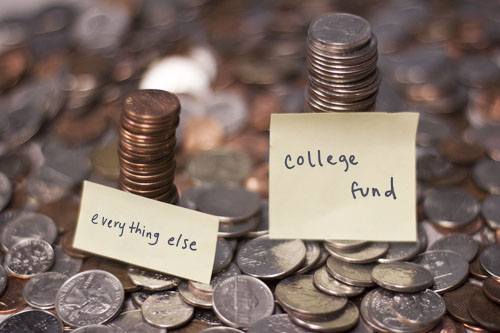

Now, a year later, we wonder what (if any) were the effects of this research. Has anything changed? Has there been any movement in the right direction? To answer: A glimmer of hope came at the beginning of this year when PSU was awarded the largest merit award—$1 million—of all the Oregon universities for graduating the most rural and minority Oregonians in 2011–12.

The university graduated 818 students in this underrepresented demographic and that’s worth celebrating. It’s still not an even playing field, but it’s a step down the road, and one less bumpy. It means something’s happening, something’s moving in the stiff and unyielding fabric of the social structure. Though it may not signal gargantuan transformations, it’s key to celebrate even the smallest of victories.

Looking at the historical experiences of many minorities in Oregon, there haven’t been a whole lot of opportunities for celebration. The reports pointed out the consistent pattern of minorities being “treated as outsiders—and not a legitimate part of the fabric of the USA, even when residents have been there for generations and lifetimes.”

For instance, in 1911 Asians were still ineligible for citizenship, and around this time Oregon passed a law prohibiting noncitizens from owning land—convenient. It wasn’t until 1949 that the Oregon legislature lifted the ban on “aliens…working on farms, living on farms and even stepping onto farm fields.” Aliens basically meant anyone who wasn’t white.

Lest we think this treatment of minorities is archaic, as late as 1968 “red-lining”—denying loans based on ethnicity—was still a common practice. This was outlawed in theory, but research conducted by Oregon State University revealed that Oregon continued “to tolerate such practices until the 1990s by the real estate industry.”

We don’t have a good track record when it comes to fair treatment for all. Where nonwhites have, as the report details, been “denied access to traditional wealth-generating engines such as free land allotments, home ownership, business development and income protection during times of unemployment,” why would education not reflect that trend?

Minorities have experienced decades of discrimination here in Oregon, and there is no quick fix, no easy answer. It’s going to be the small but vital victories like the one mentioned above that promise change.

It will mean pushing for more than 818 graduations next time—how about 1,000? It’s going to involve engaging students in both middle school and high school, long before they’re told college is an unattainable dream. It will mean continuing to provide access and opportunity to students whose parents may have known none. It can happen. Slowly but surely. It has to.

Change also needs to happen higher up to achieve a wider impact. One of the most illuminating facts in the first report’s findings was that there was only one Latino state representative in Oregon, and none in the state Senate. Equal representation of all communities is critical to everyone’s voices being heard, not just those who shout loudest.

PSU President Wim Wiewel said, “We have made special efforts to reach out to underrepresented groups and made sure they could succeed.”

Great! We see the results, Mr. President, let’s not stop there.