This January I had the immense pleasure of turning 21 and finally reaching the legal drinking age. The night of my birthday I went out with two friends, had a few beers and ate some pizza.

Now this may come as quite a shock for some of you, but that was not my first experience with alcohol. I, like most underage college students, had my fair share of underage drinking experiences that ranged from responsible gatherings to reckless binges. Luckily for me, these binges never resulted in anything harmful and I never had that worry go through my head while I was drinking.

I have always been a proponent of lowering the drinking age back to 18. For a long time I have felt it was a civil liberties issue; I can vote, go to war, get married, move out, go to college and pay taxes, but I can’t have a beer? For me this seemed ridiculous.

Once I started college, access to alcohol ceased to be a difficult feat and I found it easy to drink every weekend if I so desired. So my entitled desire for the drinking age to be lowered ceased to be an issue. However, as I look back on all the drinking I’ve done and witnessed prior to being of legal age, I have a much better reason the United States should lower the drinking age.

Quite frankly I believe lowering the drinking age would not only make drinking safer, but it could ultimately lower the amount of sexual assault that occurs on campuses.

Following the end of prohibition, individual states were able set their own drinking age. In 1984 congress and the Reagan administration, famous for other great social policies like the war on drugs and trickle-down economics, passed a law forcing all the states to raise their drinking age to 21 or else face cuts in funding. Such legislation did little to prevent minors from drinking, nor did it make college-age drinking any more responsible.

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, every year roughly 1,825 college students between ages 18 and 24 die from alcohol-related causes. More than 690,000 students ages 18–24 have been violently assaulted by students who were drinking, and over 599,000 students in the same age group have received unintentional injuries while drinking. Perhaps most surprising is that roughly 97,000 students ages 18–24 are victims of alcohol-related sexual assault or rape annually.

According to the nonprofit Choose Responsibility, which promotes safe drinking habits, nearly 90 percent of drinking done by 18–20-year-olds is done in excessive amounts.

While a lot could be said about this trend and how it’s bad for students, their health and academics, I want to primarily focus on the potential risks this sort of behavior carries for women on American campuses.

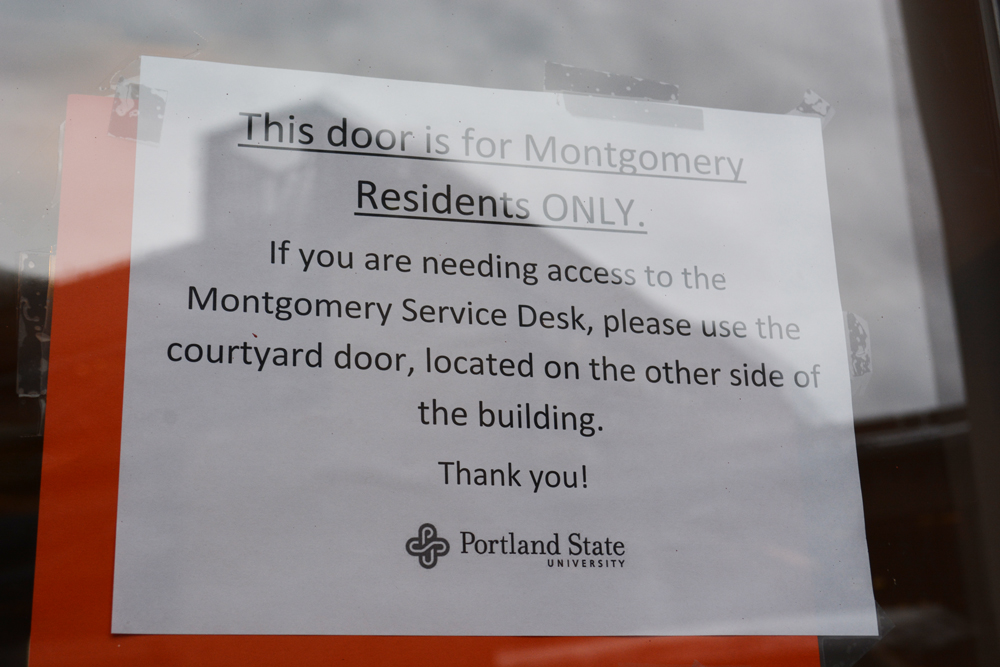

Being an urban campus, we here at Portland State don’t have a bad reputation for huge frat parties and don’t have large sporting events which attract a lot of heavy drinking. Seeing as though a large amount of our student body commutes and many are nontraditional students, we have quite a different environment compared to other campuses like Oregon State or the University of Oregon.

A study conducted by the Department of Justice found that one in five women on campus will be the victim of an attempted or completed sexual assault while in college. This same study also found that sexual assaults are more than twice as common when the victim is incapacitated due to alcohol or other drugs versus forced coercion. Along with that, 24 percent of college students who were victims of forced sexual assault and 35 percent of incapacitated sexual assault victims would consider the assailant a friend.

Another disturbing trend shows that the amount of sexual assaults that happen on campus spike around September and October when students are arriving and returning to campus.

I would argue that a lot of these trends are largely to be blamed on the drinking age.

Rather than allowing 18-year-olds to drink in an open space like a bar or at a friend’s house where they can buy their own alcohol or have it made by a bartender, underage drinking is forced underground, into the basements of fraternities and other places where students are not supervised. A bartender can cut you off or call a cab for you, and won’t hesitate to call for help when you’ve had too much. Most people have friends who can help them and watch out for them, but it doesn’t take very much for someone to take advantage of a bad situation.

Obviously the issue of sexual assault is deeper than just the drinking age, but the environment of underage college drinking can be a breeding ground for such assaults to take place.

As I mentioned previously, a large amount of these assaults are perpetrated by the friends of victims, so this means that in some cases the perpetrators are the ones drinking with the victims, and it’s someone who they might feel comfortable with walking them home or taking care of them if they drink too much. Lowering the drinking age would hopefully take away a lot of these weapons used by predators and would reduce the amount of vulnerable situations first and second-year college students can find themselves in.

Campuses try to combat such activity by handing out information and trying to encourage safe drinking behavior, but nothing is more ridiculous than having university housing staff, teachers and parents teach minors how to do an illegal action safely.

It’s clear that we need a new approach to underage college drinking that recognizes its existence. Instead of trying to fight it with legislation, we should acknowledges people’s ability to self-govern and give them the opportunity to make responsible decisions in public spaces. I’d rather see 18-year-olds at bars than in a darkened room with a drink that may or may not contain codeine. Thankfully, I’m not the only one.

In 2007 John Cardell, the former president of Middlebury College, founded Choose Responsibility, a nonprofit committed to exploring the dangers of reckless alcohol consumption and lowering the drinking age to 18.

In 2008 the Amethyst Initiative, started by Choose Responsibility, was launched and is taking a critical look at the current drinking age and has been signed by 138 college presidents, showing a shift in thought among leadership.

I’m hoping that in the future college students will treat their bodies with respect, won’t drink to excess, and especially won’t take advantage of their incapacitated peers. However, until then I think it’s clear we need to reexamine the validity of setting the drinking age at 21. Prohibition backfired miserably, and I think we are now seeing the backfire of the drinking age.