Allan Stewart is 97 years old and is graduating with a master’s degree in clinical science. This June, the silver-haired Australian will enter the Guinness World Records as the oldest graduate ever.

97-year-old man is world’s oldest graduate

Allan Stewart is 97 years old and is graduating with a master’s degree in clinical science. This June, the silver-haired Australian will enter the Guinness World Records as the oldest graduate ever.

Born in 1915, Stewart told the BBC he went back to school to “keep himself mentally active.” With six great-grandchildren, Stewart will undoubtedly stand out a little during the commencement procession, perhaps a step or two behind his classmates.

But there’s nothing slow about this graduate.

It got me thinking about the “path” to graduation we are all supposedly on. Graduate high school at 18, get an undergraduate degree in four years and start a master’s degree before you’ve had a chance to hang up your first cap and gown.

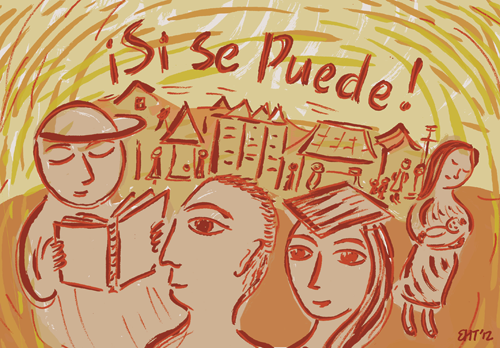

So, where did this come from? Who said this was the norm? At what point did learning get shoved into a particular timeframe? And why are people ashamed when they haven’t quite followed this format?

Because we have accepted an ideology that says there is a very clear educational itinerary and a specific way to prove the amount of one’s learning—two or three letters after one’s name.

Sure, it’s all very popular nowadays to talk about how much experience matters and the value of life-long learning. And yet, if we’re going to be honest, people who don’t follow the rules still get a second look.

I know a thing or two about that. After graduating near the top of my high school class in Kenya, I had grades that would get me into a number of good universities. Well rounded, a sportswoman and committed to volunteerism—all the ingredients for a “most likely to succeed” prediction, right? Well, that was where the predictions ended.

I moved to the U.S alone, my parents remaining in Kenya, and soon realized the path before me was full of potholes and overgrown grass, almost imperceptible at times. Our family never had much money, so I’d had only enough in my pocket for a plane ticket. So, upon arrival, as green as Kermit, I suddenly wondered what pond I had just found myself in and if I would figure out how to swim.

I had no clue how to even open a bank account and definitely had never heard of “financial aid.” So, what did I do? The first thing I knew how—got a job. Not a great one—just one that would pay the bills.

Over the next few years, I eventually found my way into a community college and signed up for classes, while working full time. After an orientation that any college would be ashamed of, I still didn’t know what a “Fafsa” was. So, despite the fact that I would easily have qualified, I paid my own way and took as many classes as my little pay check would afford.

Needless to say, this was fast becoming a journey that zig-zagged far off the intended path. Life moved on, and one by one, people my age were graduating. I felt lost and left in the dust—a failure. I kept wondering why I couldn’t seem to get my act together.

So, enough with the tragic story, right? Suffice it to say that the “most likely to succeed” student wasn’t sure she knew how to any more.

A few personal crises later, I dropped out of school altogether. And, somewhere along the way, I decided I’d missed my chance—I was in my mid-20s and had passed my due date.

The truth was, I’d made a cardinal mistake—believing I was on someone else’s schedule and not my own. Believing someone in an ivory tower knew what learning meant and that they could tell me if I was smart enough.

Today, years on, working with a non-profit organization here in Portland, I find myself back in school, facing the old demons. But then I read a story like Allan Stewart’s and blush. If someone nearing 100 years of age says it’s never too late, where do any of us get off thinking it is?

Some people will be in university for a solid six or seven years after high school—some on and off over 20 or 30 years. There are those who will balance two or three jobs at the same time; the classroom will be the office for others. Thousands of dollars of debt await many of us, and others will pay their way gradually and walk out debt-free.

The point is, there’s no one way—no one better path. And, no, that’s not someone spouting politically correct theories. It’s someone balancing life, love, job and school, knowing she can learn in each of those places.

Of course, there are days when I sit in a classroom next to someone who looks 12 and feel like a complete loser. And I will admit to insecurely easing out of conversations my friends have about the dissertations they’re writing.

There is still that gigantic elephant called “Shame” constantly lurking, trampling over a sometimes frail confidence. No matter how much you know, no matter how well you love or hard you work, the lack of a piece of paper can make you believe you’ve failed.

And that’s just plain nonsense—crippling and paralyzing nonsense. I’m pretty sure when people think of Gandhi, Mother Teresa or Martin Luther King Jr., their first question isn’t, “When did they get their degree?”

The point is not that degrees are bad. They’re part of the world we live in, how we get jobs—it’s how the system works. The point is, learning happens everywhere and at any time and to that, there is no limit.

So, congratulations to the class of 2012. Well done! And to those whose walk is still somewhere in the future, I hope you take the privilege of university learning and enjoy it thoroughly.

It’s never too late. And don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.■