My lungs were exploding. I kicked as hard as I could, pushing the puck along the bottom of the pool. A shadowy body descended from above and a fin kicked me in the head—but still I swam forward. With opposing players on both sides of me, I pushed the puck as hard as I could past the goal line and shot up for air.

Melt the ice

My lungs were exploding. I kicked as hard as I could, pushing the puck along the bottom of the pool. A shadowy body descended from above and a fin kicked me in the head—but still I swam forward. With opposing players on both sides of me, I pushed the puck as hard as I could past the goal line and shot up for air.

“Nice swim,” my teammate said. “Everything feels better after a goal.” I rubbed my head where the fin had hit me and laughed.

When I first heard the words “underwater hockey,” I thought it was a joke. I had no idea how that would even work, but one Google search later I learned that underwater hockey is an internationally recognized sport, and that the Portland underwater hockey club holds open practices every Tuesday night at 8 in the Mt. Hood Community College Aquatic Center pool. Intrigued, I dug my snorkel out of the closet and joined them.

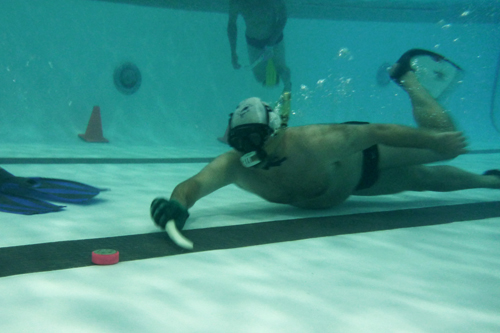

Underwater hockey is similar to ice hockey but played in a pool with a dive mask, snorkel and fins. Teams of up to six active players use small wooden sticks resembling foot-long shoehorns to push a lead puck along the bottom of the pool toward the goal line. The sticks are colored black or white to indicate teams. Players wear protective gloves and swim caps with ear guards to prevent injury, despite the sport’s “no contact” classification.

Gameplay involves players diving as deep as six feet to push, pass and block the puck, while opposing players try to steal or block passes. Unlike ice hockey, underwater hockey has no goalie. Also unlike ice hockey, players have to hold their breath to make a play, which is why this sport’s existence is met with raised eyebrows and quizzical looks.

“I like to play weird sports,” said Jorge Filevich, founder of Portland’s underwater hockey club. Eager to attract new participants, Portland’s club is coed, open to all ages and skill levels and provides equipment to those who need it. The first practice is free, after which practices cost $10 to help pay for the pool rental. Instruction for first-time players is friendly, welcoming and provided by some of the best players in the world.

“We want to get Portland to embrace it,” said Filevich, who has been playing underwater hockey since 1993. Also playing with us was the former captain of the Australian women’s team, Tania McLeish, and the Netherlands’ elite division coach, Sandor Duis. (Last week I had no idea this sport even existed, and suddenly there I was getting blocking advice from a professional.)

Another unique aspect of this sport is the subtle connection between players: “You cannot communicate underwater; everybody needs to know exactly what they need to be doing,” Filevich said. “It isn’t like in soccer where you can say, ‘Hey, I’m behind you!’”

Once in the water, players dive—twisting and turning, maneuvering like fish during a feeding frenzy. As exhausting as it is entertaining, underwater hockey is a “completely 3-D sport,” Filevich said. “You can get attacked from anywhere.”

“It’s fun and it’s fast paced,” said Josh Humbert, who has been playing underwater hockey for four months. “It’s great training for any water-based sport. It’ll increase your lung capacity better than anything.”

Sandra Bao, a first-time underwater hockey participant, was surprised by how involved she became in the strategy of the game.

“I couldn’t believe that we were playing for an hour and a half—time went by really quickly,” she said. “I got a great workout; I got thirsty. I never thought I’d get thirsty in a swimming pool.”

This is one of the benefits of underwater hockey according to Filevich. “There’s a lot of swimmers who get tired of just swimming laps, but they still want to be in shape in the water,” he said. “But [in underwater hockey] you’re doing something without realizing it.”

Judging by the muscle pain in my legs the next day, he was totally right.

I quickly realized that underwater hockey is no joke. There are several professional championships held nationally and internationally. The America’s Cup of Underwater Hockey will be held in Milwaukie Aug. 7–11, where teams from Argentina, Canada, Colombia and the United States will compete.

People interested in trying underwater hockey for the first time are welcome to RSVP through the Portland club’s website at www.meetup.com/Portland-Underwater-Hockey. It’s an amazing workout and possibly the friendliest competitive sport I’ve played. “If people knew about this,” Humbert added, “they would come.”