Summer camp. When the topic comes up, the first thing to spring to mind might be log cabins in the woods, loudspeaker announcements or sunset cannonballs off a creaky wooden dock into shimmering waters below. Whatever comes to mind when you think of summer camp, it’s probably not video games. Until now.

A different kind of camp

[portfolio_slideshow id=54748]

Summer camp. When the topic comes up, the first thing to spring to mind might be log cabins in the woods, loudspeaker announcements or sunset cannonballs off a creaky wooden dock into shimmering waters below. Whatever comes to mind when you think of summer camp, it’s probably not video games. Until now.

On Saturday, Pixel Arts Game Education held their first-ever video game youth camp at Portland Youth Builders in Southeast Portland. The camp, which charged no admission or registration fees, aimed to teach kids between the ages of 12 and 17 how to make video games. Modules included activities that touched on the basics of how to program, animate, sculpt and design for games.

Pixel Arts is the brainchild of Will Lewis and Jeffrey Sens. Lewis, a Portland State alumni, is the founder of the Portland Indie Game Squad, or PIGSquad, a group that organizes monthly activities around the themes of game development, design and appreciation. Sens began teaching himself to program at a young age, and has a long history of instruction and community outreach behind him.

The hardest part

Lewis said that one of the goals of the camp is to teach kids how to teach themselves. Kids are taught not only how to sculpt characters and design a level, but also how to communicate effectively within a group. Failure is a possibility, but one crux of the camp is to create a safe environment for failure and to temper its sting with encouragement.

“It’s an exploratory stage where kids can get their hands dirty and see what interests them and [what] doesn’t,” Lewis said.

But making games is daunting, and there is perhaps nothing in the process more daunting than programming. Luckily, the technology of building games has come a long way since the days of having to hand-code each and every line of a game.

Newer programs like Stencyl and Snap!, visual programming tools that rely on

puzzle-like colored shapes that fit together, take the bite out of manual coding by removing it

almost completely.

“Essentially, what they’re learning are the exact same concepts that they would need to do traditional programming, without just throwing them into it,” said Lucas Crispen, who helped to mentor the programming module.

Crispen was a developer in the games industry before moving to Portland. He echoed a sentiment I had heard more than once regarding the video game camp.

“I wish they were around when I was younger,” Crispen said. “And I definitely think we need more of this.”

Location, location, location

The camp was held at Portland Youth Builders on Southeast Schiller Street at 92nd Avenue.

Lewis and Sens confirmed that the location was a very conscious decision, as one of the main focuses of the camp is community.

“We’re really working on embedding locally so that kids don’t have to make the huge bus transit or bike ride all the way up to PSU,” Lewis said.

Sens said that despite their focus on the neighborhood model, word of the camp spread far and wide. He said the camp saw kids registered from as far as Oregon City and Hillsboro.

“We weren’t expecting that,” Sens said. “One of our goals was to try and draw as much as possible from communities that were residents around this area.”

Sens said that he has been contacted by people from many differing backgrounds and locations who are enthusiastic about the game camp.

“I got a call from one of the parents, who couldn’t come today, who lives in Northeast Portland,” Sens said. “She wants us to keep her apprised of all the different things that we’ll be doing because she wants these opportunities showing up in her community.”

The program and beyond

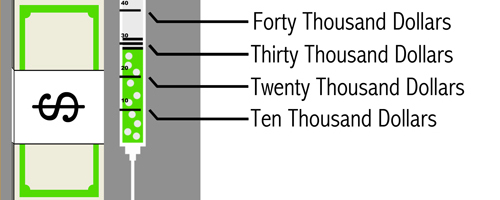

Lewis and Sens are treating the camp as a kind of pilot program. Registration was free and all of the instructors and mentors were volunteers. Still, the camp snapped up volunteers almost as quickly as it did learners. Lewis said that for every two students there was one volunteer mentor.

Sens said that the direction the camp ends up taking will largely be guided by the feedback they get from the kids.

“What we really need to know is, for all the kids of different motivations, what would they want to have happen next?” Sens said. “Do they want a two-week summer camp? Do they want programs spread throughout the year? Do they want workshops? Do they want a club in their school where they can get activities going?”

Sens said that once they have a clear vision of what kids want, they can offer a clearer picture to parents, sponsors and other allies in the community.

While the program is just a pilot right now, the lessons that kids can draw from the camp are still significant.

“I’d like to think we’ve influenced their opinions on technology and the adaptation of ideas,” Lewis said.

Additional information on Pixel Arts Game Education and upcoming youth camps can be found at gameeducationpdx.com.