Eight people were reported dead last week after a fire ravaged a clothing factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, according to USA Today. This is the most recent incident to hit the country and its garment industry after last month’s factory collapse, in which 1,000 people died.

There have been questions about the safety of workers in these factories for years—you’d think that such a massive loss of life would end any doubt of the need for changes.

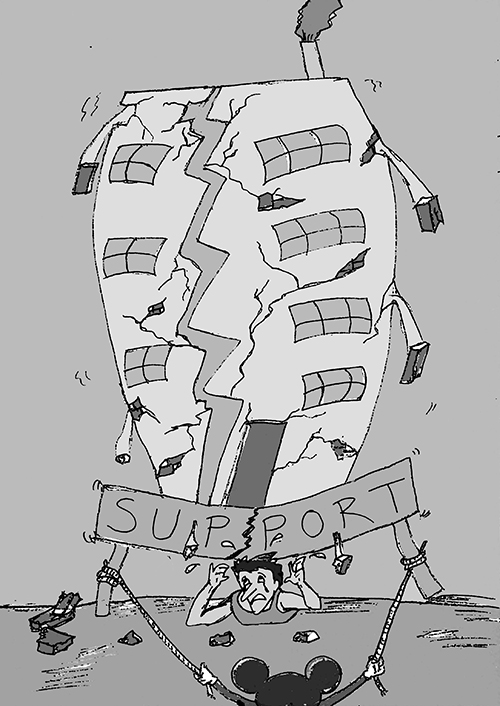

If the response of The Walt Disney Co. is any indication, we’ll have to keep on hoping.

The company announced it’s pulling its textile production out of Bangladesh. So now, on top of the unimaginable tragic loss of life, the country could face a possible long-term economic collapse. Some see Disney’s move as just the beginning of a massive withdrawal of large Western companies in a “too much liability—hit the road, Jack” scenario.

In an interview with The New York Times, Mohammad Fazlul Azim, a member of the Bangladesh Parliament, expressed concern at the implications of such a situation: “The whole nation should not be made to suffer…This industry is very important to us. Fourteen million families depend on this.”

The garment business makes up the bulk of Bangladesh’s export industry, bringing in more than $18 billion a year, according to The New York Times. With millions of its citizens living in poverty, Bangladesh can’t afford to lose this critical part of its economy. However, most of the major Western players are remaining mute on the issue, hoping we’ll forget they have their greedy fingers wrapped around Bangladeshi spools

of yarn.

Galen Weston, the chairman of Loblaw, a major Canadian brand that produces the Joe Fresh line, spoke out about the disaster and the need for his and fellow companies to be part of the solution. Few retailers have echoed his urgency, though. “I’m troubled by the deafening silence from other apparel retailers on this issue,” he told The New York Times.

There’s nothing unusual about the silence. Large Western companies have successfully remained unaccountable for their overseas practices for years. They’ve consistently gone into developing countries and paid their workers peanuts while providing them with minimum levels of job security and safety in order to sell us clothes at fabulously marked-down prices. Then, when things get inconvenient, they slip out the back door.

If you asked a panel of CEOs if the first rule of success in business is to take care of their employees, they would nod emphatically and talk up their employee-appreciation programs as if they’d discovered the concept themselves. I suppose what makes it so convenient is that, “technically,” the Bangladeshis aren’t “employees.” No doubt they are “contracted laborers” or something of the sort. There’s always some convenient technicality or loophole involved.

If ever there was a time for company owners to show a semblance of humanity, it is now. If they have any sense of what is honorable and just, they will take this opportunity to invest in the long-term safety of the factories they use and the people who make it possible for them to even make their clothes.

Labor advocates have created a compensation fund for the victims of the tragedy and their families, but retail giants like Wal-Mart and Gap have “balked at embracing” it due to concerns over its “binding legal commitments,” The New York Times reported.

If 1,000 of their employees died here in America, there’d be no concerns over “legal commitments”—or if there were, they’d be over whether the CEOs themselves would end up in jail. High-level executives would be fired left, right and center, and the storm of devastating press would be addressed immediately with commitments to making things right, no matter the cost.

The only reason they can get away with it now is that, to them, Bangladeshi men, women and children don’t have faces, names or families. They have ID numbers, unit counts and performance ratings. Perhaps Gap or Wal-Mart CEOs should look at the newspaper picture of Reshma, the young woman who was pulled alive from the wreckage after

17 days. Oh, wait, they can’t. She disappeared from the headlines long ago.

Maybe one day these millionaires will understand that treating people with dignity and humanity is not only just and honorable, it also makes good business sense. But until then, we have a thousand reasons not to buy their clothes.