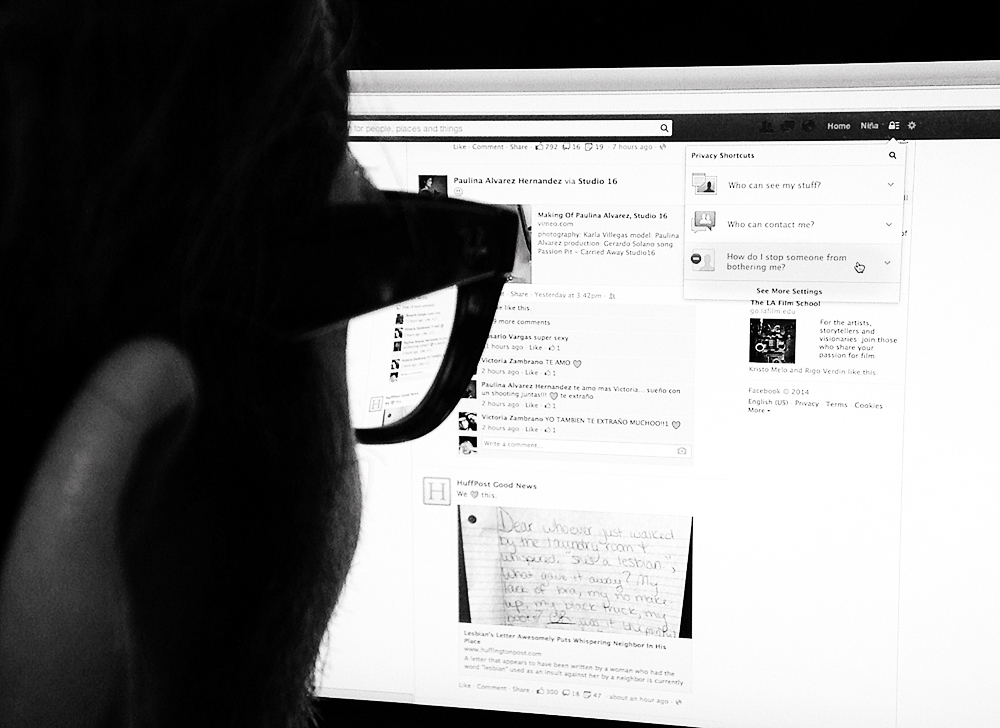

Imagine a world where your most embarrassing tweets could determine your status as a student, your darkest Tumblr posts could be shown to your team’s athletic department and your most intimate Facebook messages could be read by your Spanish 201 teacher.

The state of Oregon teamed up with the American Civil Liberties Union and TechAmerica to try to make sure that can’t happen.

Enacted Jan. 1, Senate Bill 344 prohibits educational institutions from requiring students to provide a username or password from a social media service to faculty or admissions. The bill is a companion to House Bill 2654, which protects potential and hired employees from employers who want access to social media accounts.

State representative Margaret Doherty (D–Tigard), who helped draft and back SB 344, said it was inspired by a friend’s daughter who was asked to submit her Facebook username and password as part of her application to a college. Doherty says that schools ask for this information to see a student’s character outside an academic application.

“We had heard of a few universities that were asking for access to [social media sites], and the bill started coming together. We wanted to show that if you’re applying for school or for a job, you don’t have to give up your password,” Doherty said. “That information deserves to be private.”

Oregon was one of 10 states in 2013 to pass a bill protecting employees’ electronic privacy, and one of six states in 2014 to protect the electronic privacy of students.

“Other states are following in these footsteps. Oregon was one of the first in the nation to try and tackle this issue,” Doherty said.

Priya Kapoor, an associate professor in the department of international studies at Portland State and a communications expert, says that the bill serves a purpose for students.

“Although password and username requests aren’t widely practiced, given [that] jobs are hard to come by and students have less power, it is something that needs protection.”

‘Public embarrassment’

The bill passed seamlessly through Oregon’s Senate and House, though it did encounter opposition from the athletic department at the University of Oregon, which uses different tracking techniques on its athletes. Although the school uses private tracking techniques, many athletic departments believe that it will set a precedent and cause problems for athletes down the road.

“This bill will be problematic for athletic programs across the country,” said Torre Chisholm, PSU’s director of athletics. “While understanding the importance of privacy, participation in Division 1 intercollegiate athletics effectively makes student-athletes public figures.

“Under the new bill, there is a chance that both student-athletes and athletic programs will be a greater risk for public embarrassment and NCAA problems.”

Chisholm believes that student-athletes represent the school, and that their social media personas need to be monitored.

The bill does not address the use of sites like UDiligence, CentrixSocial or Varsity Monitor, which are required by athletic departments at various universities across the US and are used to track the social presence of athletes.

These tracking or “online reputation management” sites will follow athletes’ posts on Twitter and Facebook to make sure nothing controversial is shared. While the sites are legal and not required for university admissions, they may be required by coaches.

“I would say there is a clear distinction between my social media presence and my presence at Portland State,” said Linneas Boland-Godbey, a self-proclaimed video artist and social media mogul. “I use Facebook to talk with my friends and family or to promote my personal YouTube videos.

“I wouldn’t want my academic institution to know my personal information.”

Although academic institutions won’t be able to gather information to directly access your social media accounts, they’ll still be able to search students’ names or track behavior if an account is not set to private.

The bill also does not protect students from being coerced into friending or being followed by an administration member. According to The New York Times and Kaplan Test Prep, of 381 college admissions officers who answered a Kaplan questionnaire, 31 percent said they examined social media sites to learn more about prospective students.

“Social media is a huge part of our society, and on one hand you shouldn’t have your rights being taken away by someone forcing to friend you, but students should also be careful what they put on their Facebook,” Doherty said.

The bill does not, however, prevent a university’s administration from conducting an investigation of a student’s conduct relating to social media, or if the student is engaging in unlawful activity with school-owned equipment.

For example, in 2011 a student at the University of California at Los Angeles posted a public rant about the amount of Asian-American students and their apparent behaviors around campus.

While the video raised concerns of hate speech, the school had to conduct an examination to determine whether or not the student’s actions qualified her for expulsion. According to the text of the new bill, if a student behaves in a way that is contrary to their school’s code of conduct, the school is allowed to investigate their social media presence.

The bill’s language does protect students who do not have probable cause to be under investigation.

Doherty said the bill will be re-examined in the near future to see its effectiveness, and where student protection can go from there.

“We come from an age of surveillance—there are all sorts of devices that check on the business we conduct and our public life,” Kapoor said. “There is already so much surveillance in everyday life, and social media is yet another medium that is reflective of our personal lives.

“If our privacy is not being taken into consideration, everyone will be affected.”