The job of a journalist becomes increasingly difficult as news articles are more regularly posted on Facebook and retweeted on Twitter because of eye-catching titles rather than content.

The race is on to grab readers who may not even begin reading the content but are instead sharing a story for others to see because the headline causes a stir. And to make matters worse, news outlets themselves seem to chase after increasing the number of social media “shares,” neglecting the actual content of the writing.

Recently, the science articles I’ve come across have sported headlines that are just plain misleading. I see them spread across the Internet with comments expressing disbelief or amazement at information conveyed in the title but contradicted in the body of the article.

Case in point: Nathaniel Rich’s article in the Nov. 28, 2011 issue of The New York Times made me cringe as I read the headline: “Can a Jellyfish Unlock the Secret of Immortality?” The multipage feature is not, as the headline leads the reader to believe, about immortality, or even jellyfish for that matter.

It is, in fact, a portrait of a Japanese scientist studying the ability of a type of hydrozoan (while related to jellyfish, they are not jellyfish) to repeat its entire lifecycle indefinitely.

However, the organism is very fragile and must be constantly cared for by the scientist to ensure it stays alive. While the researcher continues to study the organism’s ability to regenerate, it isn’t linked to any discoveries about

immortality.

Immortality refers (obviously) to an organism’s ability to live forever. The hydrozoans have an ability to reverse their growth process and start it over again, which in itself is very interesting, but nonetheless very different from being “immortal.” The misleading title is simply unnecessary.

While it frustrates me that The New York Times publishes sociologically inclined features that are masquerading as scientifically based, they are definitely not the only ones to blame.

The same phenomenon presents itself in small public interest stories, such as NPR’s Dec. 9, 2012 article, “The Brontosaurus Never Even Existed.”

The article actually explains that there is now an understanding that the Brontosaurus was first identified by a scientist who believed that the Apatosaurus was a different dinosaur. We now know that the Brontosaurus skeleton he found was just a more complete skeleton of an Apatosaurus. They are, therefore, the same dinosaur.

Not quite a case of the Brontosaurus never having existed.

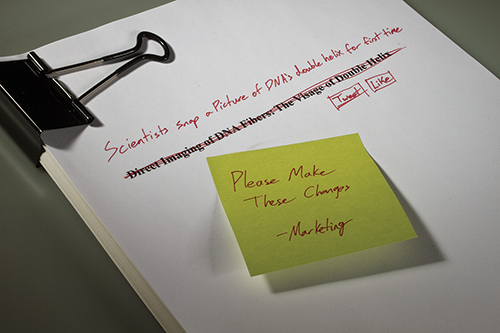

Exaggerated headlines also take journal articles and frame them as major breakthroughs, such as George Dvorsky’s article, “Scientists snap a picture of DNA’s double helix for the very first time,” published in io9 on Nov. 29, 2012.

As The Guardian’s Stephen Curry quickly pointed out, this claim is simply untrue.

What actually happened was that the scientists discussed in the article took a high-contrast electron microscopy photo instead of an X-ray crystallography photo, which scientists have been using for decades.

Furthermore, the photo released is not a clear picture of the double helix, as the headline suggests, but a picture of the structure of the DNA molecule. The scientists discuss their new method for taking a clearer picture, but it’s certainly not the first picture ever taken of the double helix.

While these exaggerations may be easily dismissed as a commonly used tool in many areas of journalism, the problem is that headlines are often an individual’s only source of news.

Science journalism already faces an uphill battle in that it deals with subject matter that many readers consider unapproachable. Many times, it is. This makes the science journalists’ job reporting science stories more difficult because they’ve got to live up to exaggerated headlines in an attempt to gain readers.

Science writing, whether exploring a breakthrough or profiling an extended study, can be exciting, but an exaggerated headline does it

a disservice.

Science writing is not political writing. There are no fiscal cliffs or general elections; there are experiments that take place over years and involve teams of researchers, and sometimes the advances are minute and unremarkable to most observers.

Science journalism shouldn’t be treated in tabloid fashion, with flashy headlines that devalue the significance of the actual findings, or judged by its number of “shares” and retweets.

The fields within science are constantly evolving—pieces of a puzzle slowly being fit together. There’s no need to pounce on every advancement as if it were breaking news.

Let us instead present science articles for what they are: information about our natural world, in which advancements and discoveries are hard to come by but are nonetheless endlessly fascinating.

No need for flashy headlines—the truth is good enough.