Nearly eight years have passed since the shocking Abu Ghraib prison photos surfaced on CBS’s 60 Minutes II and in Seymour Hersh’s New Yorker article. The United States Department of Defense subsequently removed 17 of the military perpetrators from duty, and 11 soldiers were convicted by court martial and dishonorably discharged. Two of the torturers, Specialist Lyndie England and her former fiancée, Specialist Charles Graner, were sentenced to a combined 13 years in prison for their actions at the military prison in Iraq.

But what is often forgotten about the “sadistic, blatant and wanton criminal abuses” of Abu Ghraib—as Army Maj. Gen. Antonio M. Taguba’s report described them—is that they received little news coverage until the photographs themselves were unearthed.

On Jan. 16, 2004, the U.S. Central Command released a brief statement ensuring that “an investigation has been initiated into reported incidents of detainee abuse at a Coalition Forces detention facility.” The press release was mentioned in several major publications but was ignored by newspapers such as the Washington Post. By March, reports began to surface that photos of prisoner abuse and torture existed, but it was not until CBS and The New Yorker published the photos that the story exploded.

As the photos reached the public domain, the narratives began to proliferate. The Bush administration and military officials painted the atrocities at Abu Ghraib as isolated incidents perpetrated by rogue officers, while organizations such as the International Red Cross found the torture and abuse to be part of a widespread system of military torture and mistreatment.

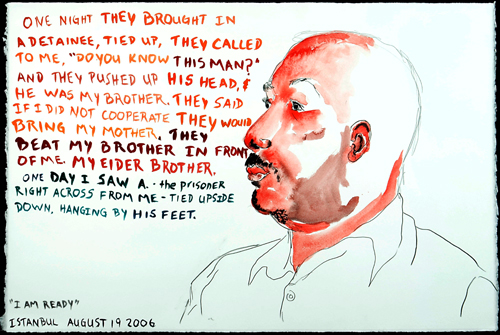

But regardless of the ever-changing stories behind the photos, the photos themselves remained the same: incontrovertible visual testimony to unconscionable mistreatment at the hands of the U.S. military. While the images galvanized some people into protesting the abuses, others became slowly desensited to such acts of criminality.

The power of an image to provoke, to embolden and to inure—and the difficulty in forming an ethical response to the more horrific ones—is the subject of author and scholar Sarah Sentilles’ upcoming lecture, “Art, Religion, and Torture: Constructing an Ethical Response to Violence Against Others,” to be held Wednesday, Feb. 15, at Portland State.

Sentilles, who earned a bachelor’s degree at Yale, a master’s in divinity and doctorate in theology at Harvard, is the author of the 2011 memoir Breaking Up with God: A Love Story. Her most recent scholarship “investigates the intersection between Christianity and torture,” Sentilles said.

“The question that is driving my talk is ‘What will it take for us to see torture?’” she said. “I feel like we see it in newspapers and photographs, and we hear about it in stories, but there’s something about how we see it that needs to be transformed so we can respond ethically to violence.”

The Abu Ghraib photos and the public’s reaction to their release struck a chord with Sentilles, causing her to abandon the dissertation idea she had been working on and begin focusing on the ethical implications of torture.

“I’m interested in the ambiguity of images,” Sentilles said. “On one level, by continuing to look at these images, we’re participating in the humiliation and violence that these people in Abu Ghraib experienced.”

How our society reacts and responds to torture is colored significantly by religious dogma, according to Sentilles, and for the largely Judeo-American U. S. that generally means Christianity.

“Christianity has at its center a tortured man. There are communities for whom that story of torture supports policies of violence, and there are just as many communities for whom that story helps them resist violence,” she said. “If you think about God in this way, if you think about a God who demanded the violent sacrifice of his son, what does that do to your mind, and what work does that do in the world?”

Sentilles’ examination of our culture’s complex and conflicted responses to images of torture is what compelled the Portland Center for Public Humanities to incorporate her talk into its Religion Matters lecture series, co-sponsored by Portland State’s Religious Studies program.

“It’s an important topic,” said Marie Lo, PSU English professor and director of the center. “What is our relationship to torture when people represent it in aesthetic forms? Does that disengage us, or does it compel us more forcefully, in a new way, to ethically demand an end to torture?”

In an age when spiritual discussion tends to be more recalcitrant than tolerant, the Religion Matters lecture series aims to diversify the points of view on offer.

“Our [society’s] discussions about religion are so polarized. There is no room for complexity,” Lo said. “What we’re trying to do, and what Sarah’s work tries to embody, is to move away from the entrenched. Knowledge and faith are constantly being tested, and they evolve.

“Art, Religion, and Torture: Constructing an Ethical Response to Violence Against Others”

Wednesday, Feb. 15, 4 p.m.

Smith Memorial Student Union, room 296

Free and open to the public