As Black Lives Matters founders Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi prepared to speak on Tuesday evening, chants of “Disarm PSU” erupted in the audience.

Tometi and Garza spoke at the Stott Center as part of Portland State’s “Living the Legacy” event series, a collection of campus and community events honoring the memory of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The women have been touring the country to cultivate discussions about race relations in America, encouraging individuals to unite against police violence and social injustices.

Along with Patrisse Cullors, Garza and Tometi helped launch Black Lives Matter, a national organization seeking to rebuild the black liberation movement.

BLM began in 2012 following the high-profile acquittal of George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watchman who shot and killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, an African-American high school student.

Zimmerman’s acquittal prompted Garza to compose a love letter to the black community. Tometi recalled the letter’s content during a media session Tuesday evening. “Despite this verdict, we know that our lives matter and that we have a duty in this period to rise up and defend black life.” The letter concluded with, “Our lives matter. Black lives matter.”

Garza’s letter was the genesis of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag, which spread organically through social media outlets and eventually led to organized groups mobilizing the movement to the streets.

“What we saw with the hashtag was that folks were willing and able, and we as organizers took it to the streets,” Tometi said.

The connection of people online and in communities led to the mobilization of 500 black people to Ferguson following the shooting of Mike Brown, a black teenager killed by a white Ferguson police officer.

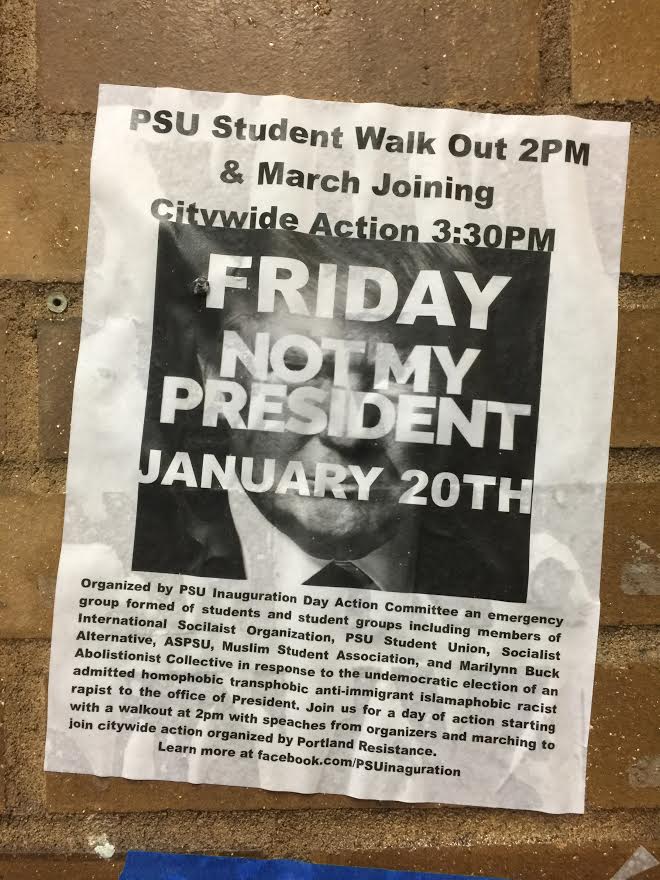

The arming of campus police officers continues to be a contentious topic within the PSU community. DisarmPSU and the PSU Student Union have both voiced opposition to the administration’s decision to arm officers. The arming of campus police was recently discussed as a student concern during a Black Caucus event held by the Black Student Union.

“[Campus Public Safety] has been a hot-button topic for quite a while now,” said Jasmine Westmoreland, programming director for the Black Student Union, in an interview earlier this month. “The black students feel that the campus has no regard for them or their safety in general. . . Our concerns should be taken more seriously.”

Tometi and Garza discussed some of the ways that police reform could be approached, though they both alluded to the need for more comprehensive change in favor of surface-level solutions. The women highlighted the imbalance of funding between local law enforcement and programs that serve community improvement. They also expressed concerns about the lack of oversight and transparency in police forces and questioned the practicality of solutions that have been raised, such as proposed body cameras on police officers that wouldn’t allow the public access to camera footage.

Tometi recalled a study conducted by UCLA in which law enforcement was found to see black youth as much older than their non-black peers. “I think that these types of implicit biases that play out are really impacting,” Tometi said. “I know that they’re impacting our communities and the outcomes when there are these interactions with people of color—black folks in particular—and law enforcement.”

The demilitarization and reform of police is a priority for the organization, echoed by audience members Tuesday night. The group has a list of guiding principles—including collective value, restorative justice and loving engagement—through which they hope to inspire, “an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise.”

Walidah Imarisha, associate professor of Black Studies at PSU, took her Oregon African American History class to the event.

“I thought it was important to take them, so that we can connect what has happened here in the Black community in Oregon with the ongoing inequalities Black communities here and nationally continue to experience,” Imarisha said in an email.

Imarisha pointed to PSU professor Karen Gibson, who talks about a “continuous thread of resistance” throughout Oregon black history, and how it is vital to show that that thread remains unbroken today.

“[That thread] is part of a web of Black communities resisting oppression nationally and globally, and it was powerful to see those threads of resistance are also very much alive and vital right here on PSU’s campus, where student organizers are courageously connecting movements for justice on campus to national and international movements like Black Lives Matter,” Imarisha said.

Garza and Tometi emphasized that the success of the BLM movement is absolutely dependent on the support and participation of all groups, whether marginalized or not.

“It doesn’t benefit any of us to have certain segments of our population have privileges and benefits at the expense of other populations,” Garza said. “There’s something deeply embedded in the fabric of this nation that does actually privilege the experiences of some folks over others.”

When asked what non-black community members could do to contribute to the movement, Garza and Tometi emphasized working where you are to dismantle structural racism and challenge anti-black racism.

“That’s bigger than diversity,” Garza said. “That’s bigger than multiculturalism. That’s certainly about a deep listening to the experiences of people of color and other marginalized groups.”

The women suggested cultivating spaces where groups can exercise their leadership and help shape alternatives to structural racism. They also emphasized supporting groups who are organizing, whether by providing a space, generating resources or just listening in a non-defensive way and placing yourself within their experience and relating differently in order to better be a support and ally.

Garza explained that people are often paralyzed by a fear of doing something wrong, which keeps them from taking a risk or standing up in support of their marginalized neighbors. She discouraged this way of thinking, acknowledging that mistakes are inevitable, but that’s understood.

“It’s better for you to do something wrong than to do nothing at all . . . It’s really important to take as many risks as your black counterparts.”