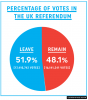

The UK referendum to leave the European Union, also known as Brexit, passed on Thursday June 23, after 52 percent voted in favor.

Economic fear and panic is spreading throughout citizens, countries and corporations of the world.

However, this is only the first step in order for the UK to leave the EU. British Prime Minister David Cameron must “invoke an agreement called Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty,” an article enforced since 2009. The UK is still under EU law until the agreement is made, and the process will take another two years, according to BBC.

Not only has this become a global issue, it has spread across the internet and social media like wildfire. People around the world are angry, especially younger age groups whom this may be affecting in the long run. Millions of signatures were collected at an online petition against the EU referendum, only to be further investigated, it was hijacked by bots that signed thousands of fake signatures.

Despite this global divide, Portland State Professor Michael Wright from the Department of International and Global Studies gives a clearer picture of what is happening in an email interview with the Vanguard.

VG: The voting percentages came close at 52 percent voting to leave and 48 percent to stay. Why is there such a big divide in the UK? Based on the populations who voted, why do you think there is such a divide between the younger and older voters in the UK?

Michael Wright: There are a lot of different factors that drive different people to vote for or against, and it will be the subject of a great deal of research that still remains to be done. My reading and instinct is telling me that this is largely a question of identity. Regarding the youth, I think that young people generally are much more comfortable living in a cosmopolitan Europe than their parents and grandparents are. They don’t remember a Britain outside of the ‘Common Market.’

VG: Was this pressure to leave the EU recent, or has it been a concern for some time?

MW: The United Kingdom has always been an awkward member of the EEC/EU. It never adopted the most meaningful elements of European integration (the common currency and the free-movement zone). A part of this was that Britons have long been very ambivalent of participating in the project of integration. The current crises (the economic troubles of southern Europe and the refugees) have made this a very trying time for Europe, which made it a very likely time for the British electorate to vote to leave.

VG: What do you predict to be the aftermath of Brexit? Is it all bad or can there be a positive effect on the economy?

MW: I’m sure Britain will recover from any fluctuations that Brexit will impose on them—unless the hype around Brexit gets the better of the financial markets. A lot will depend on how they negotiate their future relationship with the EU. They will probably negotiate a relationship similar to that enjoyed by Norway and Switzerland, which enjoy special access to the single market without being at the decision-making table in Brussels. The real key will be the access that London’s financial sector will have, but I’m confident that they will be able to secure themselves a good place. In the long run, the UK is now free to set its own regulations, but if British producers want to continue exporting to the single market, they will have to continue to adhere to the EU’s standards—standards the UK will no longer have the power to influence. In the long run, it will be good for British producers producing for the domestic market, but difficult for producers producing for the continental market. Thankfully, they will have the short-run benefit of a weak pound against the euro.

VG: How can the U.S. be affected by Brexit? Can it affect an even more local area like Portland? If so, how?

MW: Visiting the UK will be a little cheaper for Portlanders. Other than that, I don’t think we’ll notice much if anything. What’s more important is that the same social movement that supported Brexit is one that we have here in the United States. Portland is a very cosmopolitan place (like London, which largely voted against Brexit), but the country surrounding Portland (like England around London) is much more ambivalent or outright rejectionist of the forces that are part and parcel of globalization. The Donald Trump phenomenon very much rhymes with the Brexit phenomenon.

VG: What can prevent the exit?

MW: Parliament could choose to ignore the result of the referendum, but it would do so at the peril of its democratic legitimacy. That would be a horrendous mistake, I think. Right now, the British political elites need to make themselves legitimate again in the eyes of their constituents, which means listening to them. British democracy, as well as the legitimacy of democratic governance in most, if not all, of the western democratic world is being challenged, and it needs to find an answer to that challenge. More interesting is if Scotland and Northern Ireland (which both largely voted to ‘remain’) could somehow veto the outcome of the referendum. Just like Parliament, I think it would be a mistake for them to veto the result. Who knows, maybe they will change the relationship with the rest of the UK, and maybe they’ll find a way to remain or return to the EU once they’ve done so.

VG: Anything else you would like the PSU community to know, feel free to add.

MW: I think it’s important not to think of Brexit itself as a world-altering development. As I said, the most far-reaching aspects of European integration (the common currency and the free-movement zone) are aspects that the UK had opted out of to begin with. What’s more important is wider phenomenon of peoples rejecting integration and globalization, and how this is coming from people who are older and less urban. It is coming from people who are being left behind by these things. They have a right to be upset, but they should also get upset at the right things. The EU was symbolic of the social and economic developments that have left them behind, but it’s not necessarily the cause of them.

Professor Wright will also be teaching a European Union class in the fall, which he encourages students to take.