A recent study shows that the majority of crimes committed on the Portland State campus aren’t perpetrated by members of the PSU community—a problem endemic to PSU because of its non-traditional urban setting. One of the downfalls to being at the heart of Portland is the fact that PSU is easily accessible to the public, resulting in crimes not usually associated with college settings. And many of those crimes involve heroin or other drugs.

Campus heroin use on the rise

A recent study shows that the majority of crimes committed on the Portland State campus aren’t perpetrated by members of the PSU community—a problem endemic to PSU because of its non-traditional urban setting. One of the downfalls to being at the heart of Portland is the fact that PSU is easily accessible to the public, resulting in crimes not usually associated with college settings. And many of those crimes involve heroin or other drugs.

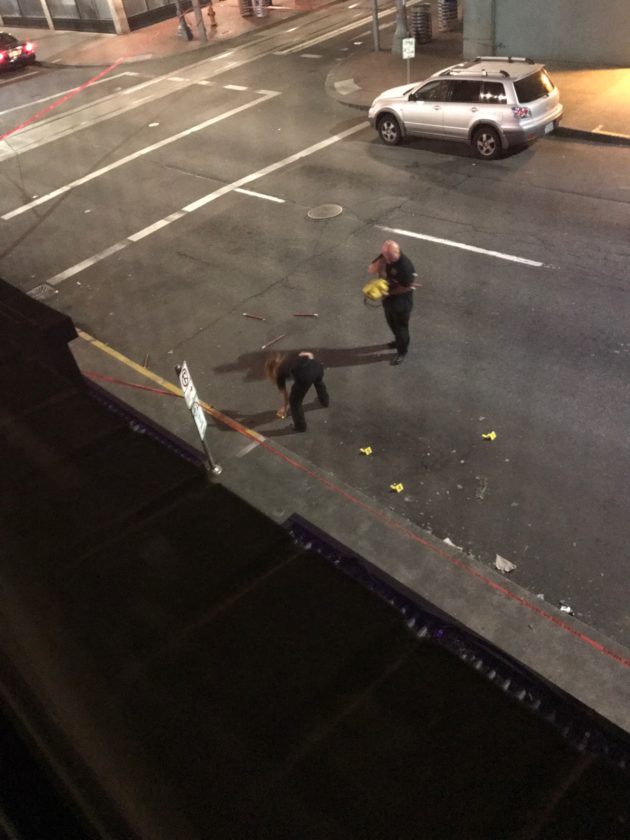

Heroin-related arrests on campus have significantly increased since 2010. Clery Act statistics released by CPSO showed that last year, the number of heroin-related arrests on campus increased to 66, while the total number of all drug-related arrests in 2010 was only 34. While the issue of heroin on campus is a problem by itself, it also reflects the larger problem of heroin use in downtown Portland.

“We are located in an area that has significant problems with heroin,” said Phil Zerzan, director of CPSO. Additionally,

Zerzan explained that PSU’s location, the large campus, and its diverse student body make it difficult for CPSO to identify who should and should not be on campus. “We have greater accessibility to outsiders,” he said.

Over the last six years, Kris Henning, PSU professor of criminology and criminal justice and associate dean of the College of Urban and Public Affairs, collaborated with Campus Public Safety to collect data on campus crime. Using a database that he helped to design, Henning and CPSO were able to determine the kinds of crime on campus and the percentages of criminal offenders. As Henning analyzed the data, he found that 81.2 percent of all crimes were committed by people unaffiliated with the university.

The data revealed that there were approximately 1,146 arrests involving non-university offenders. Henning took a random sampling of 188 individuals from this pool, and with assistance from the Portland Police Bureau, successfully identified all of the suspects and commonalities between them. 87.2 percent of suspects had prior criminal records. “A large percentage has extensive criminal records,” Henning said. “Some of the people CPSO are dealing with are chronically involved with the criminal justice system.”

PSU’s non-traditional environment makes it difficult to find solutions to the problem of criminal activity. “Portland State is unique. At OSU or OHSU, there’s a better idea of who is supposed to be on campus. Most of the crime is student-on-student crime,” Henning said. “That’s not really characteristic of what urban commuter schools have to deal with. What we know about those communities doesn’t apply here.”

In addition, it’s challenging to find ways to identify repeat offenders. “You can’t even tell in an office setting who is supposed to be there and who is not,” Henning said. “We have no access control; it’s very difficult for us to do.”

Seventy percent of suspects from Henning’s sample had a history involving substances, ranging from alcohol to illicit drugs. And some of those suspects can be violent. According to Zerzan, three CPSO officers were involved in heroin-related violent altercations last year. “On occasion, people who are likely to go to jail will resist, sometimes violently. It’s difficult,”

Zerzan said.

Sergeant Pete Simpson works in the

Central Precinct of Portland Police Bureau. Central Precinct works closely with CPSO, assisting with investigations and proving additional resources to campus safety officers. Heroin is a problem across Portland,

Simpson said. “I do know definitely that heroin is on the rise city wide,” Simpson said.

The cause, Simpson explained, is an increase in oxycodone addictions. The prescription drug, an opiate used to relieve moderate to severe pain, can lead to physical and psychological addictions. Heroin is a pain-relieving drug that was synthesized from morphine, which is a direct derivative of the opium poppy. Over the counter, oxycodone costs $4 per pill, but at street price, pills can cost $25–40 each, according to Center for Substance Abuse Research.

Users who cannot afford the price or cannot get a prescription then turn to other drugs for the same effects.

“An oxy tablet can cost two to three times more than a hit of heroin,” Simpson said. He explained that people can turn to heroin for “purely economic reasons” and that

heroin is a drug that “spans all socioeconomic groups.” Additionally, Simpson said that it’s likely PSU students use heroin, adding, “It’s happening on a lot of college campuses.”

Portland has faced problems with heroin abuse since the 1990s. Statistics from the Oregon State Medical Examiner show that between 1991 and 1999, there was a steady increase in the amount of drug-related deaths in Multnomah County. Heroin was shown as the most deadly drug with 195 deaths associated with heroin in 1999.

Heroin-related deaths in Oregon again rose in from 89 in 2006 to 118, showing an increase by 32 percent in a single year. In 2007, there were 63 heroin-related deaths in Multnomah County alone.

In the last few years, deaths have dropped. 2010 statistics show 50 deaths in Multnomah County, followed by 10 reported deaths in Washington County, making Multnomah County the leader in heroin-related deaths. Oregon data has consistently shown heroin to be more deadly than methamphetamines and cocaine.

Zerzan said that CPSO is working hard to find solutions to heroin problems on campus. “It’s a tough job ahead of us,” Zerzan said, “but we’re trying.”