Charles Bernstein, the “postmodern jester of American poesy,” will bring his idiosyncratic and playful poetry to Portland State, with the help of the English department’s creative writing master’s program.

Challenging conventions

Charles Bernstein, the “postmodern jester of American poesy,” will bring his idiosyncratic and playful poetry to Portland State, with the help of the English department’s creative writing master’s program.

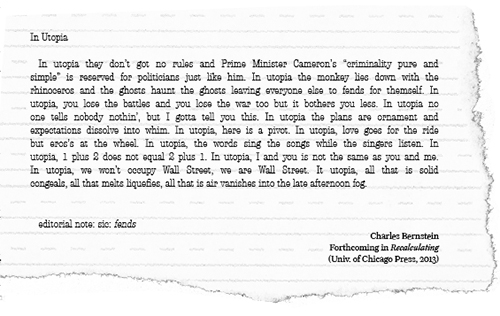

Bernstein will read selected poems from his approximately 40 books, including the career-spanning All the Whiskey in Heaven and the forthcoming Recalculating.

Currently a professor of poetics and poetry at the University of Pennsylvania, Bernstein has had an expansive career in literature and language. Bernstein cofounded and coedited L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Magazine, a publication that promoted avant-garde poetry and writing.

Bernstein spoke with the Vanguard’s Jeoffry Ray about art, language and poetry in the digital age before his upcoming visit to PSU.

Vanguard: How did your interest in writing begin?

Charles Bernstein: I grew up on the Upper West Side in Manhattan. We were the first generation to grow up with a television in our rooms. In my early years I got into visual arts and music, concerts and jazz clubs. But my interests always centered on verbal language and thinking of verbal language as a sort of medium of “stuff” to work with, like a sculptor would work with a material or a painter with paint, rather than thinking of poetry in a conventional sense.

I had this verbal stream going on in the back of my head, all the time; different cascading formations of words shaping themselves as I read heavily through philosophy and literature. As I entered into college, I was involved with the antiwar movement and the counterculture that was developing in New York and elsewhere at the time. In college I studied philosophy, with a special interest in Wittgenstein.

At that time, I was interested in thinking about poetry in a philosophical context and about how language as a medium or substance affects and reflects reality, perception and our ideas of who we are. I was very involved in theater, too. All of those sorts of avant-garde, performance works, and all of those things combined led me on a course of writing essays…which brings us to today.

VG: You were involved in publishing L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Magazine and the Language Poetry movement, years ago. Would you be interested in explaining a little about it?

CB: I edited L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Magazine with Bruce Andrews from 1978 to 1981. We wanted to have a forum for discussing formal, conceptual, performative and ideological perspectives on poetry. It was a journal of poetics. We also had people writing essays in nontraditional and nonexpository forms. But nonetheless, they were essays, addressing poetics. That magazine was one of a number of forums through which Language Poetry emerged.

VG: Can you explain a little about Language Poetry, to give people a little context for it, versus other more traditional forms?

CB: I tend to like to say that Language Poetry does not exist, and I now tend to speak about the expanded field of language.

VG: Can you talk a little about your own writing, and the inspirations through which you work?

CB: In my work, I tend to use many different structures and forms. Rather than having a book that is composed of a single style, a lot of my books seem like group shows or parades of different approaches to writing. I’ve really been doing that for a long time, so a lot of my books are composed in this way, with oft-conflicting tones and radically diverged forms.

At the heart of the activity is trying to make work in which the tone is its own entity and speaks for itself, rather than my speaking through it. So I’m not representing my voice or my speaking in the poem, nor directly conveying my feelings as a biographical individual outside the poem.

Nor am I describing anything that exists in a fixed, factual way outside the poem, as you might have in a snapshot or a photograph. The poem creates its own world and its own reality, and the sound shape and rhythm that’s created in the work move together in a fluid field to create an experience.

VG: Beyond your writing background, I understand you’ve also worked across other fields, such as music and the visual arts. Would you like to talk a little about those experiences?

CB: I’ve been interested in collaboration right from the first. One of the things that was sort of the hallmark of what we were doing in the ’70s around the magazine was to question what exactly was the relation of the individual self to a poem, and to what degree did a poem express a self, or present a person who already existed. Or did poems actually explore what self and voice were?

So the movement was from “voice” to “voicing,” and to make it plural. Collaboration is very interesting because you’re creating something that is a product of more than your own thinking and judgment. The big collaboration that I did in the early ’80s was called L E G E N D, which I did with four friends. It was a huge work of multiple parts, in which we collaborated in every two or three, and then one that all five of us did.

That was an exhilarating movement outside of a personal composition. In later years, I collaborated with composers writing libretti, as in the visual arts. Mostly I’ve collaborated with my wife, Susan Bee, on a set of books. We’ve made a number of verbal/visual collaborations. I’ve also done collaborations of that kind with Richard Tuttle, Mimi Grosse and Amy Fillmin.

VG: In terms of the modern information age, how do you feel poetry is evolving and being received in this age of texts, Twitter and iPads?

CB: A lot of my writing in my newest work, Attack of the Difficult Poems, deals with the relation of new media to poetry. I think one thing poetry can do is be on the forefront of exploring all possibilities of new media. Rather than answer the question thinking something big happened 15 years ago, I think the larger frame is that, since the 19th century, there has been a transformation in language reproduction that’s most dramatically affected by sound reproduction, radio and sound recording.

A reading by Charles Bernstein

Monday, Oct. 1, at 6 p.m.

Smith Memorial Student Union, Room 236

Free and open to the public

The new media of the Web has actually made accessible the archive of sound recording of poetry in just the last 10 years, even though it’s long existed. Al Filreis and I, in 2005, started an archive called PennSound, which is the largest digital archive of poetry recordings in the world.

Thousands of sound files of hundreds of poets are all available for free and can be downloaded as MP3s. It’s made available a crucial aspect of poetry via sound recording that had previously been hard to come by. So that’s just one example of how the poet’s performance and recital of their work becomes available through the new media.

VG: Which of your works would you recommend to interested students as an introduction to your work?

CB: I’d be happy to answer that question, sure. [Laughs.]

I would say that probably the best thing to start with would be the selected poems All the Whiskey in Heaven, which came out a few years ago through Farrar, Straus and Giroux in an easily available book. It tried to create an overall experience, from beginning to end, of my work from 1975 to 2010.