Will Eisner isn’t a household name, but when it comes to comics, he should be at least as ubiquitous as Stan Lee. Known as the father of the graphic novel, Eisner revolutionized sequential art with the seminal A Contract with God in the late 1970s. The comics industry’s highest honors, equivalent to Oscars, are called Eisner Awards for a reason.

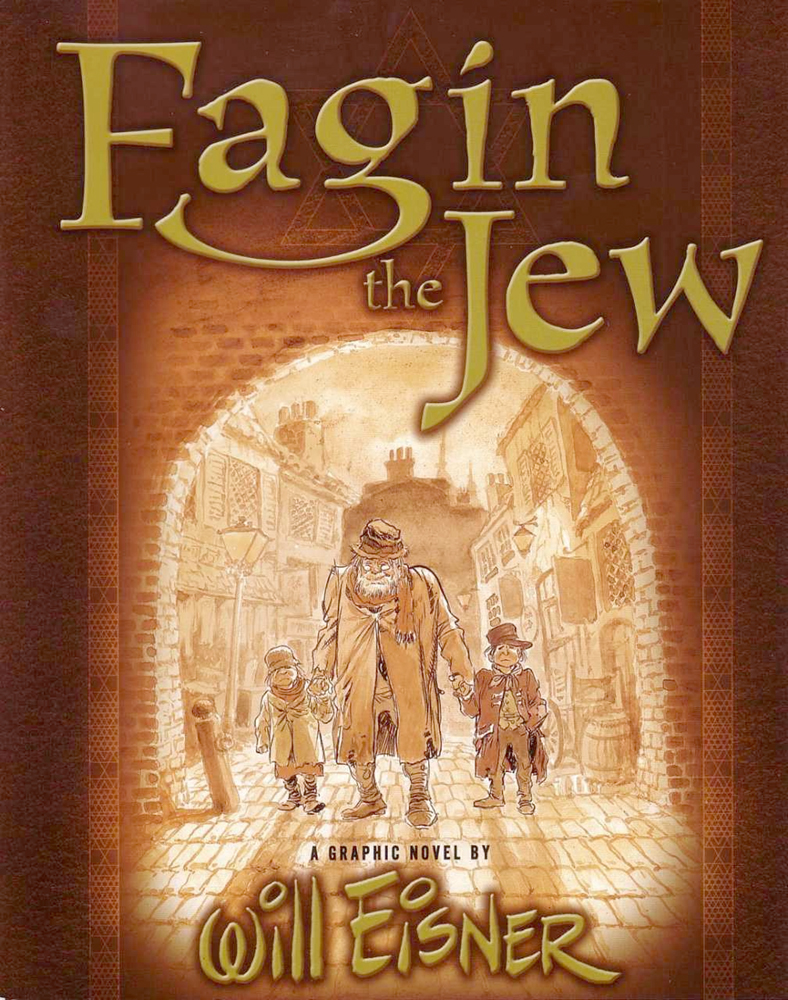

One of Eisner’s last works, Fagin the Jew, is now being reprinted in a special 10th anniversary edition from Dark Horse Comics. Fagin the Jew attempts to retell the classic Charles Dickens story Oliver Twist from the villain Fagin’s point of view as he tries to set Dickens straight the night before he is set to be hanged for his crimes.

The story isn’t so much an exoneration of Fagin as much as it is an explanation of how he became the despicable child corrupter we see in Dickens’ original novel. Though the events of the classic story are retold, much of the book shows us Fagin’s own childhood. Born into unfortunate circumstances, bouncing from proprietor to proprietor, Fagin’s life as a boy is a dark mirror of Oliver’s.

As evidenced by the title, Eisner sets out to explore Dickens’ portrayal of Fagin not only as a villain, but as a Jew. The name of the book comes from the first few printings of Oliver Twist, in which no direct derogatory language was used, but where Fagin was referred to as The Jew repeatedly.

This kind of well-meaning stereotyping is something that Eisner was all too familiar with. In his classic crime-fighting strip The Spirit, Eisner created a sidekick named Ebony. First appearing in 1940, the character was a black caricature through and through, from his swollen lips to his borderline-minstrel dialect full of “Yassuh!” and “No suh!” Eisner meant no harm in creating the resourceful but goofy supporting star, but it’s an uncomfortable and undeniable part of his storied career.

“You’d think that Will would choose to delve into an African-American character or story or historical figure,” says Marvel Comics writer and former PSU professor Brian Michael Bendis in the Dark Horse edition’s new introduction.

“Instead, Will took his complicated feelings about race and caricature and applied them directly to his feelings about Judaism and how Jews have been reflected in the media for hundreds of years, by sinking his teeth directly into the classic Oliver Twist and one of the most famous Jewish stereotypes in all of fiction… Fagin.”

As Bendis also points out, the book attempts to understand how someone becomes a stereotype. We see Fagin go through many of the same trials that Oliver undergoes as a child, but the various caretakers they each run into take much more of an immediate shine to the blonde, doe-eyed Oliver.

The environment around Fagin, from his swindler father to the local crooks to the justice system itself, all work against him. By the time Oliver comes into Fagin’s care, Fagin is a bitter curmudgeon with more respect for money and station than other human beings. There’s still a soft spot in his heart buried somewhere beneath his hardened scales, but Fagin figures that since society sees him as irredeemable, it may as well be true.

The story is told with soft watercolor, layered in swaths of blacks and grays. Eisner was a master storyteller, even towards the end of his life, and it shines in Fagin the Jew. There aren’t any traditional comic panels boxing up or separating moments, but the story moves flawlessly from page to page.

The characters are expressive and nuanced, with just as much attention paid to a crooked smile as a missing button on a shirt. Everything from the cobblestones on the street to books on a shelf is bathed in an otherworldly light that gives a warm glow to even the darkest scenes.

As engrossing as Eisner’s art can be, his knack for dopey dialogue can sometimes pull the reader out of the story. At one point, two characters are arguing that a man named Benjamin Disraeli could never be prime minister, but anyone familiar with history of the era (or access to Google) will know that Disraeli was twice prime minister of the United Kingdom.

Towards the end of the book, Dickens is taking his leave of Fagin and adds “…er, oh, in my later books I’ll treat your race more evenly!” The admission doesn’t do much for the character of Dickens, who mostly exists for the story’s point of telling, or for Fagin, who doesn’t receive much vindication from the offhanded remark. That leaves only the reader, puzzled over the half-hearted fourth-wall breakage.

If you haven’t read Will Eisner’s work, well, you should probably start with the Contract with God trilogy. But after that, Fagin the Jew should provide a thought-provoking afternoon in a time when things seemed a little more black and white.