These days almost every other political speech echoes the woeful tale of the American student. Our plight is discussed in grim correlation with our country’s future. No pressure. We made it into the State of the Union—it wouldn’t be a good one if there weren’t a few depressing statistics, right?

President Barack Obama introduced his administration’s latest attempt at supporting a debt-free education. College Scorecard is an interactive search engine where students can check out schools based on various criteria, including region, potential occupation, campus setting and size. What it also allows us to do, more importantly perhaps, is compare and contrast schools based on several financial factors.

A search within 50 miles of downtown Portland pulls up 32 colleges and universities, each broken down into five categories: tuition cost, graduation rate, loan default rate, median borrowing and employment. For example, it shows that the cost of a year at Portland State is $12,168. This number reflects the average cost after grants, scholarships and financial aid are applied. You can then compare this cost to, say, the University of Portland, which is $28,407 per year.

The median borrowing category is especially helpful, as it breaks down the average monthly loan repayments for students over a 10-year period.

What many students say once they’re already caught in the quagmire of debt is, “I didn’t realize how much it would add up.” Thanks to the scorecard, before you even apply for a loan or school you’ll have an idea what you’ll be paying each month for the next 10 years. That’s an empowering piece of information to have.

There’s a fair amount of controversy around this new system, not the least of which is whether the federal government should be involved in helping students decide which school to go to. There are concerns about the last category—the “average earnings of former undergraduate students who borrowed Federal student loans.” Students could easily misread this as a guarantee of a job when, as we all know, there are none of those!

But if we have to err one way or another, it should be on the side of more information. I’d rather know all I can and then take responsibility for the decision I make.

So, this is helpful, definitely, but it’s not a magic debt-avoider. We’re still the ones who have to pay the bills. They haven’t found a system that will do that for us yet, no matter what Mitt Romney said. Not everyone’s parents are a surefire fallback plan.

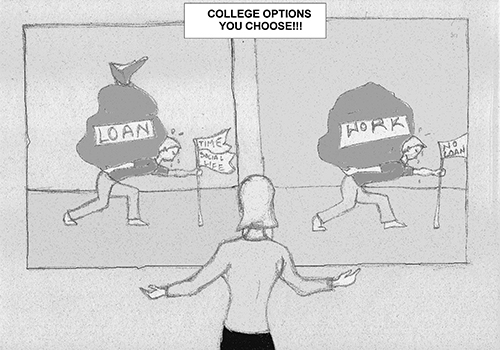

Is it even possible to avoid standing with a diploma in one hand and a pile of bills in the other? It can be done, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it’ll be fun. An article in The New York Times followed the stories of several undergraduates as they made their way through the obstacle course of school, work and, possibly, a life. They all had different methods—one worked as a server, one joined the military, another worked at a hotel. They did have one thing in common, though. They all worked.

Going to school and not working is a luxury few of us can afford, and as tempting as it can be to focus solely on your education and then work later, when you’ve got the degree, it’s just not feasible. The job market is kind to no one these days. It’s a toss up that the job your degree is supposed to produce for you will even be there when you’re done. So, working and schooling is the new black.

Another common thread that connected the successful debt-dodgers was the lack of a crazy social life. Most said they filled their extra time with as many shifts as possible and that joining a fraternity or sorority wasn’t even a consideration. The idea that college meant four years of nonstop partying didn’t apply.

It begs us to consider that if we want our college years to determine our future, we should choose to forego some luxuries now, make some tough and smart decisions and have something more than stress to show for it. Work now, party later? Sounds

like a plan.