While the U.S. Government has spent—and is currently spending—billions of dollars in the War on Drugs in Mexico, the real cost of the war is measured in blood. The New York Times reported that between 2006 and 2012, “more than 55,000 Mexicans and tens of thousands of Central Americans [were] killed by drug-fueled violence.”

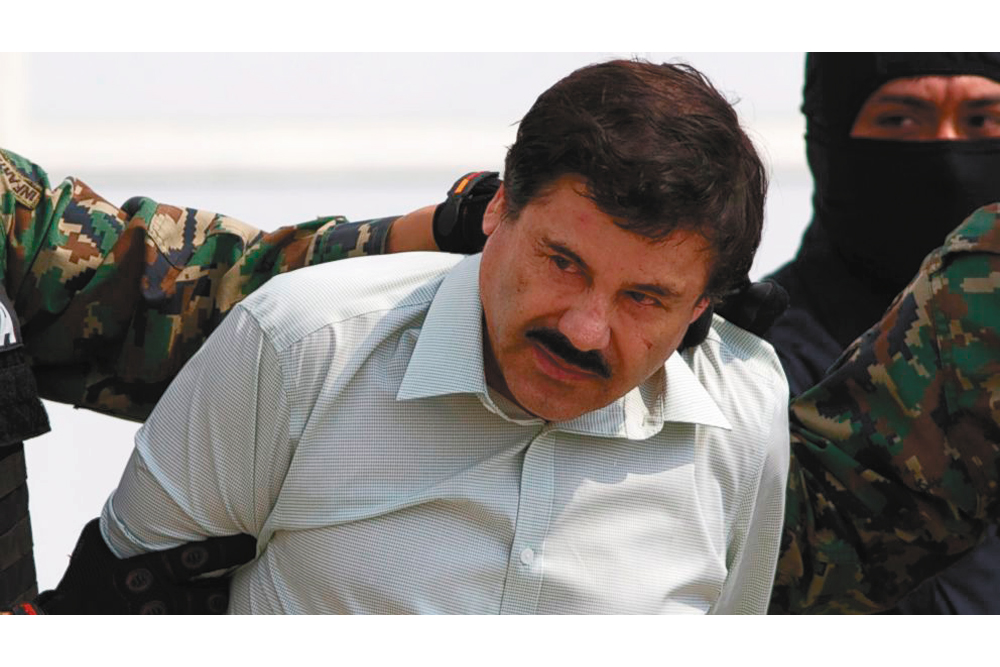

The Sinaloa Cartel is one of the world’s largest crime syndicates. Based in northwestern Mexico and headed by the world’s most wanted drug lord, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, the Sinaloa Cartel leaves a trail of death and destruction in its wake.

The history of violence within drug cartels highlights the questionable nature of an agreement made between Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel, the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. According to an investigation by El Universal, citing court documents of corroborating DEA and Department of Justice testimony, U.S. officials and Sinaloa Cartel officials met 50 times between 2000 and 2012, particularly the period from 2006 to 2012.

According to Business Insider, the Sinaloa Cartel would provide U.S. authorities information about rival drug cartels and, in exchange, the “U.S. would dismiss its case against the Sinaloa lawyer and refrain from interfering with Sinaloa drug trafficking activities or actively prosecuting Sinaloa leadership.”

I interviewed a Portland State student and second-generation Mexican-American, Tyler Gonzales-Aguirre, to find out what he thought about the DEA’s deal with the Sinaloa Cartel. He said that the deal was “unsurprising, but it’s important to empathize with the Mexican people.” He said that he has had a relative die due to cartel violence and concluded by saying that “the people of Mexico don’t deserve that.”

As reported by National Public Radio, the administration of former Mexican President Felipe Calderon followed the U.S.’ lead by also favoring the Sinaloa Cartel in the government’s War on Drugs, focusing much more intensely on the Gulf-Zeta Cartel, one of the Sinaloa’s rivals.

While the Sinaloa appeasement strategy is intended to mitigate violence in Mexico, it also had a direct effect on drug-related violence in Chicago, Illinois, as the Sinaloa Cartel provides the lion’s share (70–80 percent) of the drugs, especially heroin, in Midwestern states across the U.S., with Chicago acting as the Sinaloa’s import hub.

While El Universal has no information as to whether the U.S.-Sinaloa Cartel agreement continued past 2012, the arrest of high-ranking Sinaloa members in Chicago and the arrest of the Sinaloa’s boss “El Chapo” Guzman makes it appear that the agreement is no longer in effect.

Despite the effectual end of the U.S.’ agreement with the Sinaloa Cartel, the Mexican government still seems unable to stop Mexican authorities from aiding the Sinaloa. Recently, corrupt prison officials allowed Guzman to escape his maximum-security prison in Mexico, an even more daring escape considering that U.S. officials had warned the Mexican government about several escape plots in early 2014.

When I asked Gonzales-Aguirre about corrupt Mexican officials, he said, “Of course they’re corrupt; if someone threatened your family, you’d do probably what they want.”

As college students in the Pacific Northwest, we are very isolated from the violence and fear looming over northern Mexico and the streets of Chicago. Marijuana legalization has steered profits away from violent cartels; however, whenever people buy hard drugs, they are not only hurting themselves but indirectly funding the drug violence destroying people’s lives across North America.