To kick off the new Hellenic Studies program at Portland State, art history Professor Anne McClanan has invited a series of guest speakers to visit PSU and talk about Greek topics from ancient times to the present.

Devotional selves in a Christian empire

To kick off the new Hellenic Studies program at Portland State, art history Professor Anne McClanan has invited a series of guest speakers to visit PSU and talk about Greek topics from ancient times to the present.

One of these speakers, Ivan Drpic, assistant professor of art at the University of Washington, will give a lecture Friday, May 18, in the Art Building on art and identity in the last century of the Byzantine Empire.

Drpic’s lecture will focus on Byzantine epigrammatic poetry and, more specifically, how Byzantine devotional epigrams shaped the identity of their patrons.

Though centered in modern-day Greece and Turkey and dominated by Greek-speaking peoples, the Byzantine Empire continued the Roman Empire in the east as a Christian empire.

“The Byzantines referred to their own empire as the Roman Empire and called themselves Romans,” Drpic said. “One of many names of the ancient city of Constantinople—modern Istanbul, Turkey—is the ancient name “Byzantium,” or “Byzantion” in Greek, that became applied [by 16th century historians] to the entire empire, culture and civilization.”

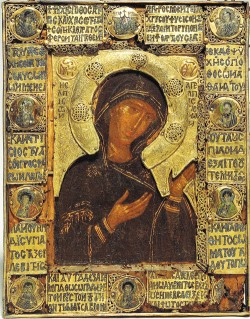

Epigrams, which are poetic inscriptions on objects, formed a rich collection of literature from the Byzantine Empire. Several of the epigrams Drpic will discuss state the name and origin of the object they relate to, and most of these objects possess religious significance.

“Nowadays we would call these objects works of art, but for the Byzantines they were various kinds of devotional objects, primarily icons,” he said. “I also deal with other devotional objects such as reliquaries, inscriptions on textiles, embroideries, some inscriptions on monumental architecture, also fresco paintings and mosaics.”

The epigrams tell the story of where these objects came from, who commissioned them and what the people from that time period thought of themselves.

“There has long been a misconception that individual identity emerged from a certain period associated with modernity,” Drpic said. “I’m mainly trying to argue that these texts and objects working in concert are projecting not only a persona in social terms, but also a whole sphere of devotion and religion.”

The objects, which were extremely important to the Byzantines, reflect a site of self-representation, so that personal devotion and piety themselves became a form of self-representation and expression in Byzantium, according to Drpic.

For the Byzantine Empire, the inscribed artifacts served a primarily religious purpose, with their looks serving only as a secondary function.

“They were complex and multifaceted objects in which their aesthetic dimension was definitely important but not the key. There were other aspects which were much more important,” Drpic said. “This is one way in which their culture differs from our culture.”

The conservative, hierarchical society of the Byzantine Empire lived by strict rules and conventions. This often leads some people to believe that Byzantine art is essentially all the same, but Drpic disagrees.

“Within these conventions, within these established norms of behavior, there is an entire discourse about art and about donation and about the proper religious decorum,” Drpic said. “However, I think there was enough space for a playful engagement with these conventions and also a kind of creativity.”

Epigrams served as a medium for social identity during the Byzantines’ heyday.

“This realm of personal piety really allowed people to creatively engage with works of art and to confession their own personae through works of art and text,” Drpic said. “I would say the major difference [between their culture and ours] is the mode of expression available to them, but the underlying concerns, the driving force behind it, are the same: the nature of humanity.”

The distinction between public and private spheres of life did not exist in the Byzantine Empire. Epigrams and icons were often intended for personal use but were later donated to churches and viewed by wider audiences.

“Through these objects, you are addressing, on one hand, this devotional sphere—a saint, or Christ, or the Virgin Mary—but you are also addressing your social peers, your social environment,” Drpic said. “So personal and devotional in Byzantium is always social at the same time and also political.”

Drpic came from Serbia, on the northern fringe of the former Byzantine Empire. There, he gained an interest in Byzantine history, art and culture because it gave birth to his own culture. He obtained his doctorate at Harvard University and began teaching at the University of Washington in September 2011.

His lecture showcases his current research on Byzantine epigrams, and he hopes for positive feedback from the audience so he can write a book on the subject. Drpic became interested in these epigrams because they offer a rarely studied and unique perspective on Byzantine art and culture.

“This entire corpus of knowledge has been neglected by scholars. Here we have a huge body of texts dealing directly with art and coming from a really unique environment,” Drpic said. “Epigrams were composed for members of the elite by professional poets, and they reflect and reveal a great deal about this elite culture.”

A lecture by Ivan Drpic: “Devotional Selves: On Art & Identity in Byzantium”

Friday, May 18

Art Building, room 12

10 a.m.

Free and open to the public