As a young college student, one of my primary concerns is finding a job after graduation. It’d be even better if said job allowed me to utilized the English degree I’ll have in June 2014. I don’t worry so much about the competition between men and women in my chosen career field. That wasn’t always the

case, however.

Feminist forefront

As a young college student, one of my primary concerns is finding a job after graduation. It’d be even better if said job allowed me to utilized the English degree I’ll have in June 2014. I don’t worry so much about the competition between men and women in my chosen career field. That wasn’t always the

case, however.

An article recently published by The Oregonian profiled a local woman who deserves to be called a local legend. Betty Kendall worked as an auto mechanic during the 1970s. She graduated from Portland Community College with an associate’s degree in auto mechanics.

Nowadays a female mechanic doesn’t seem like such a shocker, but back then it was a very rare occurrence. In fact, trade jobs were usually male-dominated, but during the recession of the 1980s women began populating the trade workforce. Kendall, a certified master mechanic, now works with other tradeswomen at Oregon Tradeswomen Inc. to help them “access careers in nontraditional blue-collar work,” according to

The Oregonian.

In documenting the thousands of Oregon women who’ve been a part of our state’s blue-collar history, Kendall and others at Oregon Tradeswomen mark an important advancement in our workforce. Kendall said that, despite her education and certification, finding employment wasn’t easy. “Many people didn’t understand why a woman would ever want to be a mechanic,” she said.

Kendall faced being called a “starry eyed idealist” and dealt with people who said she should “go back to being a housewife,” The Oregonian reported.

Kendall’s been working with the Tradeswomen Archives project, which aims to share the stories of women who’ve made careers doing blue-collar work. The physical archives are located at California State University, Dominguez Hills, but are also available online. The project’s website provides a comprehensive visual history of women working in the blue-collar trade as well as in other nontraditional occupations.

The website states: “Jobs in the U.S. and around the world tend to be stratified by race, gender and nationality, not so much because of ability, but because of historical and cultural practices. The efforts made by courageous women and supportive men to cross over barriers and take up nontraditional careers are valuable histories that deserve documentation of many sorts.”

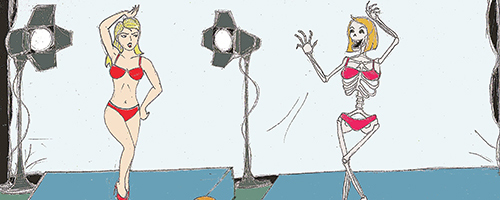

Within the last 100 years, different jobs have become more readily available for women. Not to say that we no longer need to fight for equality in the workplace—we most certainly do. The glass ceiling still needs to be shattered.

While women have an easier time finding a place in the workforce, there are still huge pay differences between men and women, and it’s becoming increasingly harder to balance career and family.

And just because the election is over doesn’t mean that the war on women is over.

Fox News recently published an article critiquing feminism and the advancement of women in the workplace and in education.

The article, aptly titled “The war on men,” (ha!) said that “[w]omen aren’t women anymore,” and claimed that “women pushed men off their pedestal (women had their own pedestal, but feminists convinced them otherwise) and climbed up to take what they were taught to believe was rightfully theirs.”

There are so many negative things one can say about those two quotes alone. Suffice to say the fight is—obviously—far from over.

Yes, we have come so, so far in the fight for equality, and that’s great, really. There’s no simple solution to wage differences, apart from equal pay for equal work. It’s still unclear as to why that solution isn’t being used across the workforce.

Jobs are scarce for everyone right now, and they will continue to be until the economy turns around. Nobody knows how long that will take, so the best thing we can do is remain hopeful and treat each other with respect.

If we keep working to further equality, we’ll be as successful as Kendall was in breaking free of the norms and gaining respect as well as employment.

Fox actually had it right (i feel dirty typing that). feminists have been conducting a war against men for decades. god forbid people be treated as equals. but nope, feminists just want to suppress men as much as possible. and the prevalence of such stupidity at PSU sufficiently encouraged me to hate women. nice going PSU. i learned to hate men in high school. now i am learning to hate women in college. iam focusing solely on individuals from now on. screw the masses!

Didn’t take much. Sounds like you were ready to hate women from the get go. Maybe you’re just a hateful person, David. “Feminist” is a fairly broad term (no pun intended). Take a step back. Do a little more thinking. Hopefully it will cure you of your misogyny.