Depending on where you live in the Portland Metro area, your home—and all its residents—may be at high risk from exposure to radon. Radon is a natural gas that is emitted from uranium-rich rocks resting in sediment deposits left over from the great Missoula floo

Geology students study local radon levels

Depending on where you live in the Portland Metro area, your home—and all its residents—may be at high risk from exposure to radon.

Radon is a natural gas that is emitted from uranium-rich rocks resting in sediment deposits left over from the great Missoula floods.

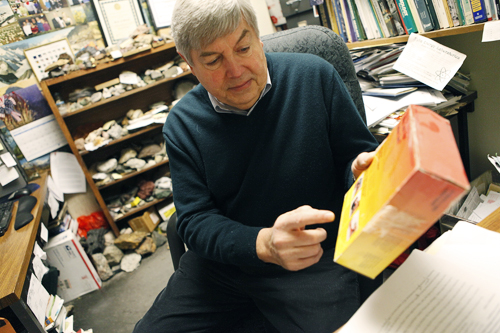

You cannot see, smell or taste radon, but that doesn’t mean it is harmless, said Portland State professor of geology Dr. Scott Burns.

“Radon is the number-one cause [of] lung cancer in nonsmokers,” Burns said.

Since 1994, Burns has been looking into the radon levels in Portland. This year, a group of PSU geology graduate students began to study old maps to find out which sediment deposits in Oregon were causing high levels of radon activity.

The graduate students took on a class project in which they began to catalog and revise the large amount of old and new data.

This year, students were able to collect data on more than 33,000 homes in 80 zip codes, getting a good idea of where the majority of radon is. The first study of radon in 1994 took note of only 1,100 Portland homes.

The data showed that one in eight homes have high radon levels and one in 15 homes have radon exposure in general.

Oregon is the first state to collect in-depth data on what its potential radon levels are, and is also the first to attempt to find out where exactly these uranium-rich rocks emitting radon are located, Burns said.

Getting your home tested can be a very simple process. There are two types of tests: a short-term, three- to seven-day test and a long-term, three-month test. The price for the test kits ranges from $12 to $25.

This is something you can do yourself, and kits can be purchased from stores like Home Depot. The test kits grade the exposure level of your house on a scale of zero to four; if your home is graded over four the Environmental Protection Agency recommends mitigation.

Mitigation involves a simple pump and fan to help push the gas from under the house and into the outside air. Simple things like opening the covers to attic crawl spaces can help circulate the air and potentially lower the effect that radon has on a home.

Typically, having your home tested and mitigated can increase your home’s value. It’s a potential selling point, Burns said.

“It’s the best geological hazard to have,” he said. Houses with basements or with cracks in their foundations can give radon a better opportunity to seep into the air circulation.

Because the Oregon Health Authority is concerned about what radon is doing to people’s health, it is raising awareness and paving the way for other states to look into their own radon levels.

Recently, the Oregon Legislature required that all new homes built in the Portland area come equipped with radon pumps and fans.

By making more people aware of the risks that radon poses to their health, the OHA, Burns and graduate students like Hilary Whitney aim to lower the number of people who are affected by radon.

“A lot of people don’t associate lung cancer with radon,” said Whitney, who participated in Burns’ project.