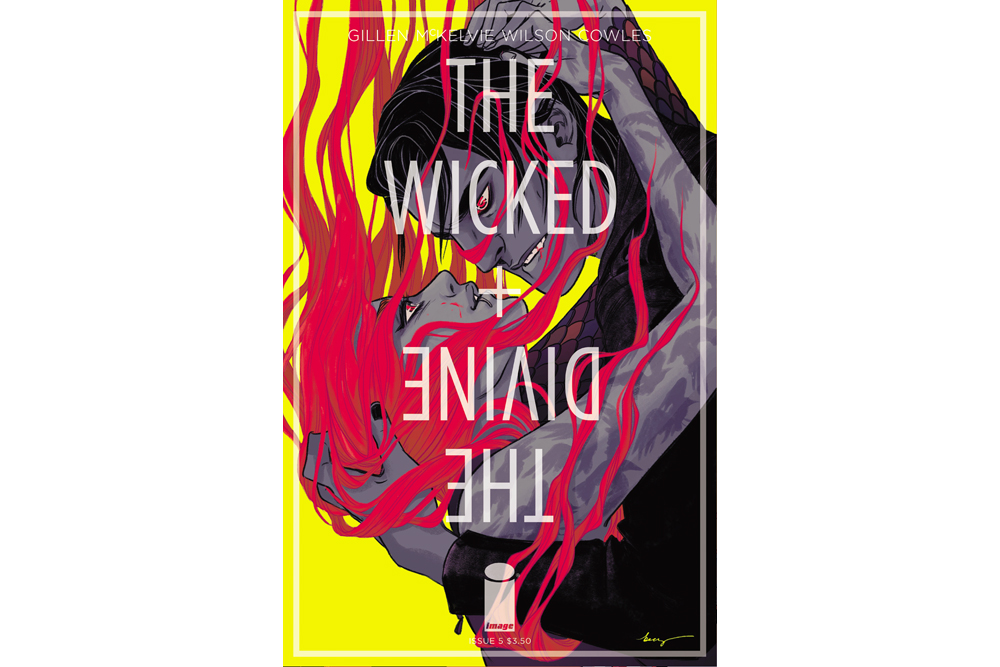

Kieron Gillen, writer of the Iron Man series “Believe,” is even better when writing original fiction.

The Wicked + The Divine is our world, but one in which every 90 years, 12 gods are reincarnated in the bodies of kids for two years before dying. These gods come from all kinds of religions and faiths.

Upon reincarnation, a kind of protector of the gods comes to these kids and tells them that they’re gods, that they are the most important thing to humanity and that they have only two years left to live.

Most of them become pop stars, of course. Suddenly you’re special, powerful, a god and you’re about to die. So go on tour, stand on stage, look people in the eye until they all cry, orgasm and faint.

Though now that I say it out loud, that just sounds like pop star concerts as we know them today.

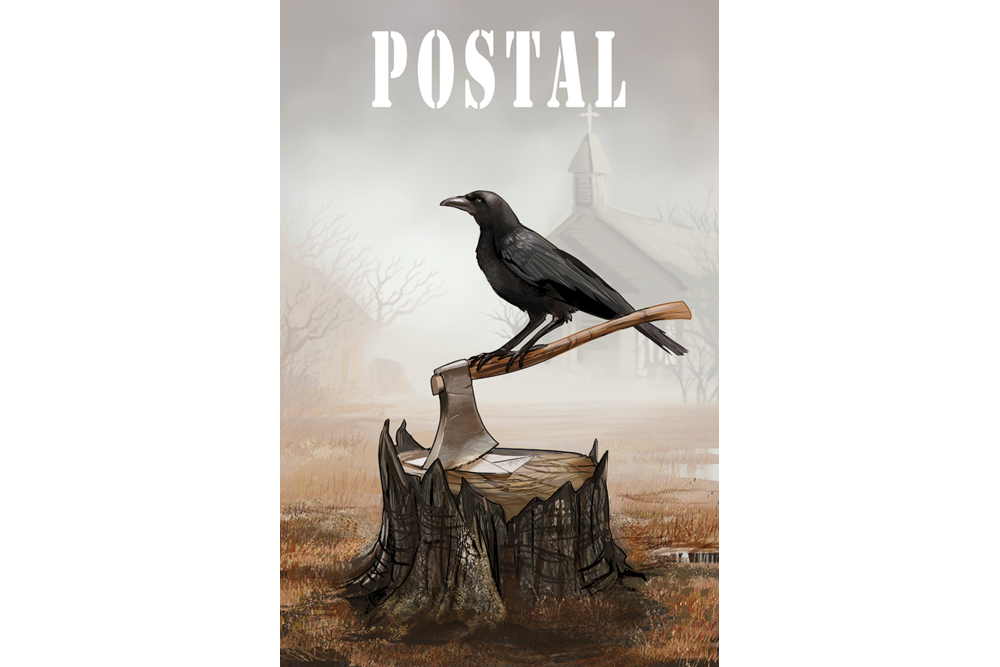

Everyone goes on a hedonistic rampage except the Morrigan, a Celtic mythological figure with three aspects and who reigns over battle, death and darkness.

She keeps her concerts in closed, underground train stations. She appears in a murder of crows flooding from the tunnel. She doesn’t have to explain herself because she’s a goddess and, more importantly, the Morrigan.

Even her fans are too frightened to say her name, any of her names. I’d want to show up to one of her gigs if there were fewer people burning to death.

Shinto, Egyptian, Roman, Nordic, Christian, Celtic, even Semitic Akkadian gods make appearances, and the diversity extends to the mortals in the story.

The protagonist, Laura, comes from a mixed-racial family. The skeptical reporter with a master’s in comparative mythology is an East-Asian transwoman who’s worried about a 17-year-old non-Japanese girl cosplaying a Shinto god.

Even Lucifer, who’s a white ciswoman in this incarnation, makes a comment that can be interpreted as transphobic and apologizes later. She’d meant to humiliate Cassandra, but never for something like that. It bears repeating: Lucifer apologizes for saying something transphobic. Lucifer.

I’m not going to pretend like she isn’t one of my favorite characters, but to be honest, they’re all my favorite characters. Laura is a 17-year-old planning to fail her A-levels so she can better focus on attaining godhood, or something similar. She’s not really sure. She just wants to be powerful.

But everyone wants to be special in The Wicked + The Divine, and Laura is very common for that. But that’s the central focus of the story: What does it mean to be special?

For the skeptics it means being flashy conmen, and for the believers it means just being as close to the gods as they can get. For the gods it doesn’t just mean having two years to live, it has more weight than even that. It means something for the entirety of humanity.

Gods don’t exist without us, and they know it. They are special and then die for us, for our inspiration, for our continuation and betterment. Our inspiration turns these kids into gods doomed to die, even Minerva in the body of a 13-year-old. Humanity’s being inspired turns these people from humans to ideas that are then consumed.

The Wicked + The Divine oscillates between the metaphorical and literal arguments, like how Baal Hadad, a young black man, is criticized for being immodest and violent in a way his fellows are not, which is perfectly complemented by Jamie McKelvie’s bright rainbow and solid shadows that define the whole book.

For a premise that sounded interesting but not necessarily deep, Gillen really proved me wrong.