You know the story: A mysterious tragedy, a surly gumshoe, an old flame, a bittersweet ending.

It’s been almost a century since Dashiell Hammett mastered the noir genre with The Maltese Falcon, but since then the same yarn has been unraveled in thousands of different ways. As mystery fans know, it’s not where you end up but the road you took to get there.

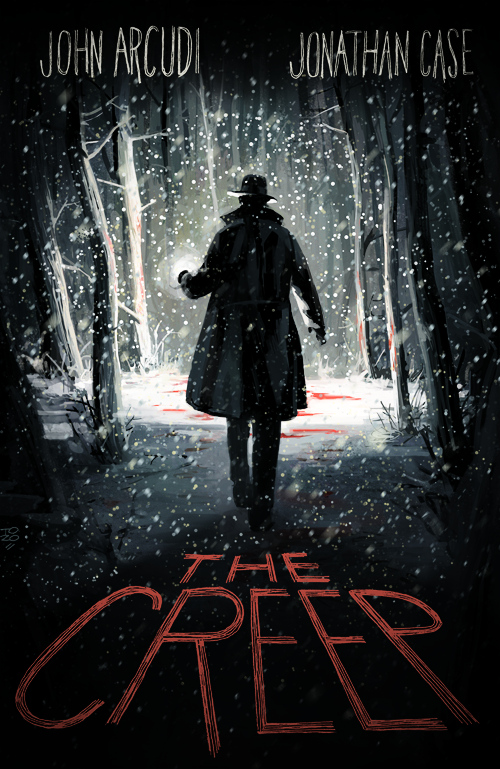

Written by John Arcudi (known for the excellent Hellboy spinoff B.P.R.D.) and with art by Jonathan Case of Portland’s Periscope Studios, The Creep centers on a detective bent on solving the mystery of a pair of teen suicides.

Oxel Karnhus is put on the case via a letter from Stephanie, the mother of one of the deceased boys. She’s an old college girlfriend from before he was a private eye—before his mug looked like the side of a limestone cliff.

A real syndrome called acromegaly, which usually surfaces in adulthood, warped Oxel’s body and face. He gets stares from little girls on the train and is harassed by youths in the street.

It’s the same pituitary disorder that gave cult icon Rondo Hatton his classic Hollywood horror look. Oxel is more or less based on Hatton, who was known as “The Creeper” after a character he played in a 1944 Sherlock Holmes film.

Though most everyone in the story reacts strongly to Oxel’s appearance, readers will be less put off. The comics medium already has a tendency to exaggerate features, so Oxel’s face only appears monstrous when juxtaposed with regular faces in the same panel. Most of the time it just feels like Herman Munster actor Fred Gwynne has taken up P.I. work.

Despite his condition, Oxel spends the novel struggling to look beyond the surface of the mystery. Unable to face his former lover, Oxel focuses on the mother of the other deceased boy, a woman named Laura, and Stephanie’s ex-husband, Greg.

Barring them, we sense that a few other things are picking at Oxel: Questions of mental illness and the sexualities of the two dead teens—best friends before death—plague Oxel in his search for the truth.

Arcudi manages to bring up these questions without asking them aloud. In one scene, Oxel is going over the case in his head while staring at what seems to be a gay couple on the subway.

One of the men lashes out at Oxel, who meant no harm, telling him that he of all people should know it’s not polite to stare. Oxel asks himself, “What the hell just happened?”

To his credit, Arcudi doesn’t spell it out, leaving the reader to come up with an explanation.

Though the back half of The Creep is a real page-turner, it takes a while to get going. We learn the names of players and their relationships with each other before meeting most of them, creating confusion as to who is who and to whom.

The disjointed introductory chapters can probably be attributed to their original format. Like many graphic novels on the shelves, The Creep first hit stands in a single-issue format and is now collected in hardcover. But the first chapter is made up of three smaller segments that initially appeared in the anthology series Dark Horse Presents.

This transition is awkward, but the story finds its groove by the end of the second chapter. From there, The Creep glides, slowly accelerating to its inevitable but shocking resolution.

Arcudi crafts an ending that is truly unexpected and horrifying, but also solves the mystery in a satisfying way.

Case illustrates The Creep with two styles. The predominant one is characterized by simple lines and cool blues and grays, conveying a bleak town with an even bleaker history.

The Creep

By John Arcudl and Jonathan Case

$19.99

Available at bookstores and comic shops everywhere

His second style is much warmer; Case portrays past events with thin, sketchy lines filled out with nostalgic red and yellow watercolors. This style is employed mostly for flashbacks, but we also see it when Oxel is on the phone with Stephanie.

With the watercolors the reader sees Oxel’s old girlfriend not as she is but as Oxel imagines her through the lens of his rose-tinted memory.

Case’s usual hard, cold style is not nearly as attractive as the scenes using watercolor, but that plays to the novel’s strengths. The past is an alluring mirage, its illusions opaque and dangerous.

The Creep moves slowly, and aside from its terrifying conclusion it doesn’t leave a strong first impression. But over time the details will start to tug at you: Like a fly buzzing near your ear in bed, the minutiae will return your thoughts to the plot over and over again, whether you like it or not.

The more time that passes after reading The Creep the easier it is to appreciate the finer points of the understated story—though that could just be the passage of time.