“Even if you change my name, I’m afraid they’ll find out who I am,” Mutab said as he attempted to calm himself by drinking his favorite Arabic tea, Alwazah, or “swan.”

“If my government finds out I am an apostate, I could be jailed when I go home,” Mutab said. After a pause he added, “Or I could be killed.” Apostasy is the act of leaving one’s religion. In traditional orthodox interpretations of Islam, the penalty for apostasy is imprisonment and death.

The Vanguard’s multimedia editor, Andy Ngo, interviewed Mutab, Faisal, and Noora, three Saudi Arabian nationals studying in Portland. For their protection, the Vanguard has changed the names of the three interview subjects.

Mutab and Faisal are students at Portland State University. Noora attends another educational institution in the area but asked that its name not be printed.

As of fall 2014, Saudi Arabia had the largest number of international students at PSU with 442 students. China had the second-largest number at 375 students.

PSU’s relationship with Saudi Arabia spans decades. The Kingdom’s current crown prince, Mohammad bin Nayef, attended PSU from 1977–80.

Established in 1932, Saudi Arabia’s origins stem from an 18th-century pact between Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab, a puritanical Islamic revivalist, and Muhammad ibn Saud, a central Arabian ruler. Their descendants continue to run state institutions today. The modern Saudi Arabian state is a theocratic, authoritarian dynastic monarchy.

Saudi Arabia’s “Basic Law of Governance,” which governs the country, states that its constitution is the Quran and the Sunna–the actions and sayings of Muhammad, the 7th century prophet of Islam–and that Shari’a, which means Islamic law, is the foundation of the Kingdom.

Clandestine atheism

Mutab and Faisal are closeted atheists and sometimes prefer to be called “ex-Muslim.” Many atheists of Muslim heritage refer to themselves as ex-Muslim in order to acknowledge the cultural traditions in which they grew up.

“Within Muslim contexts, atheism has largely been regarded as a Western phenomenon,” said Muhammad Syed, president of Ex-Muslims of North America, a nonprofit based in Virginia. “The ‘ex-Muslim’ identity allows us to deliberately stake a position that we are both from Muslim communities and reject the dogma.”

Founded in 2013, EXMNA is the first organization to provide support and advocacy for ex-Muslims in the United States and Canada.

Mutab said he left Islam after being exposed to new ideas and lifestyles in the United States. “The Islam I was raised with in Saudi Arabia is against modernity,” Mutab said. In Saudi Arabia, Mutab supported a policy he considered “gender apartheid”—strict segregation of the sexes—and intolerance of other religions, hallmarks of a fundamentalist interpretation of Islam. However, after studying in the United States, Mutab found it increasingly difficult to reject science, critical thinking and modern ideas about women and sexuality.

“Islam, as I was taught, was used to suppress human rights,” Mutab said. “I choose to follow a different path now.”

Faisal left Islam after introducing himself to philosophy. “I remember when I first got exposed to Plato’s Republic,” Faisal said. “I was shocked that a non-prophet would write something that wise.”

The Vanguard communicated with Faisal through disposable, single-use emails per his request. At home during the summer, Faisal stressed that he had to practice extra caution while speaking about his atheism.

Saudi Arabian women: “perpetual minors”

Noora is a practicing Muslim but remains equally concerned about the potential consequences of publicizing her opinions. Noora rejects Saudi Arabia’s institutionalized version of Islam, sometimes called Wahhabism, named after the country’s puritanical co-founder, ibn Abd al Wahhab.

Wahhabi Islam, also known as Salafism, is a rigid and literalist version of Islam derived from the medieval Hanbali tradition. The Hanbali school of jurisprudence is usually seen as the most fundamentalist strain within Sunni orthodoxy. Salafism is sometimes linked to the ideology of jihadist groups like the Islamic State and Al Qaeda.

“I was brainwashed to hate,” Noora said. “The Jews, Christians, non-Muslims—even Muslims not like us. There is nothing spiritual about that kind of Islam.”

Saudi Arabia bans the open practice of non-Islamic religions and has intensified criminal penalties for Sunni Islamic beliefs that steer too far from official state orthodoxy. The Shiite Muslim minority, who are concentrated in the Eastern Province, are also subject to systematic discrimination.

Noora is in favor of sexual minority rights and women’s equality, which puts her at deep odds with the state. In Saudi Arabia, women are effectively treated as perpetual minors regardless of age, and relationships outside of heterosexual marriage are criminalized. The country is known for its guardianship system which requires every female have a male guardian, or “wali al amr,” in order to travel or make most life decisions. The guardian is normally a father or brother but can also be a son or uncle.

“I’m an adult woman and my country requires me to get permission from my father to do anything,” Noora said. “This is inhumane.”

Noora said she is fortunate her father filed the paperwork granting her permission to study abroad without a male chaperone. Many female Saudi Arabian students are accompanied by a guardian if they are not given permission to study independently.

While in the United States, Noora has eschewed the black veil and robe she was required to wear since childhood. “The niqab [face veil] not only covers a woman’s identity, it ignores her existence,” Noora said.

Defiantly enjoying a glass of French wine during the interview, Noora added, “I am most homesick when I’m actually at home. I am homesick for freedom.” Possessing or consuming alcohol is strictly prohibited in the Kingdom; transgressors can be arrested, fined and lashed as punishments.

Saudi Arabian women take selfies while wearing the compulsory headscarf and abaya (robe) at a festival north of Riyadh.

An authoritarian state without the rule of law

Although not an ex-Muslim, Noora is concerned that her views could be construed as sedition or blasphemy. Saudi Arabia is noteworthy for having few formalized laws, instead relying on the judgment of exclusively male prosecutors and religious judges who define criminal behavior on a case-by-case basis. As an authoritarian state without the rule of law, the Saudi Arabian government can easily implement policies at will with limited accountability.

“The regime is reliant on the Wahhabi religious establishment for support, which means that reforming human rights in the area of religious liberty is difficult,” said Dr. Lindsay Benstead, associate professor of political science in the Mark O. Hatfield School of Government at PSU. Benstead specializes in politics and women’s rights in the Middle East and North Africa.

“Geopolitics make it unlikely that the U.S. and other countries will put much pressure, at least publicly, on Saudi Arabia to reform,” Benstead said.

Last year, an additional hurdle was added for liberal Saudi Arabians when the promotion of “atheist thought” became prosecutable under new anti-terrorism legislation through royal decree. Like the few other formalized laws that exist, wording of the legislation is vague. As a result, many accounts exist of Saudi Arabians being jailed on charges of sedition, terrorism and blasphemy.

“Anything I say or do here—online or offline—could have consequences back home,” Noora said. “It’s better to stay quiet.”

Saudi Arabia’s human rights record

Saudi Arabia’s repression of freedom of expression, association and conscience have sparked criticisms from human rights organizations. According to Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, Saudi Arabia goes as far as routinely jailing nonviolent dissidents, including children, without trial for months and years.

“Saudi authorities, namely the ruling royal family, have often used the courts to stifle and silence any critique of the political and judicial system or the excesses and control of the religious establishment,” said Dr. Elham Manea, associate professor in the Political Science Institute at the University of Zurich. Manea, who is a practicing Muslim, specializes her research in Islamism, or the ideology of political Islam, and its impact on human rights.

“The case of Saudi blogger, Raif Badawi, illustrates how dire the consequences are of criticizing the religious authorities and their conduct,” Manea said. In 2013, Badawi was convicted of “insulting Islam” for his role in co-founding and operating an online forum called Liberal Saudi Network. The website featured articles critical of the religious authorities.

Following a failed appeal in 2014, Badawi’s sentence was increased to ten years in prison in addition to 1,000 lashes and a fine of one million riyals ($266,550). After serving his prison term, Badawai will be barred from traveling or making media appearances for another ten years. His wife, Ensaf Haidar, fled to Canada and continues to campaign for his release.

Ensaf Haider holds a portrait of her husband, Raif Badawi, at the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France on December 16, 2015.

Last year, Ashraf Fayadh, a Palestinian artist, was sentenced to death based on accusations of blasphemy and atheism through poetry. Executions in Saudi Arabia are usually performed through public beheadings.

Fayadh’s death sentence was later overturned in favor of an eight-year prison sentence and 600 lashings.

Saudi Arabia is among 12 other Muslim-majority countries which prescribe the death penalty for apostasy, although executions are generally rare, according to the Freedom of Thought Report 2015. In recent years, Saudi Arabia typically sentences those accused of apostasy or blasphemy to long jail terms, public lashings and heavy fines.

These developments don’t placate Mutab’s concerns, however. “Even if my state doesn’t kill me, a fellow citizen could, and he would have legal justification based on Shari’a,” Mutab said.

Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Scholarship

Faisal echoed much of Mutab’s fears, but highlighted the additional pressures that come with studying on a government-funded scholarship. In 2015 alone, around 200,000 students studied abroad through the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Scholarship Program.

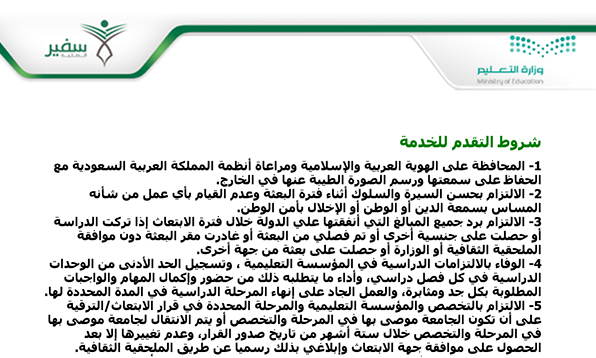

On the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Education website, the scholarship application’s rules dictate that applicants be Muslim. In Arabic, the first rule states that one must, “[preserve] the Arabic and Islamic identity while observing the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s laws and painting a good picture of it abroad.”

Rule two continues: “Maintain good behavior while on scholarship and not engage in any act that could undermine the reputation of religion, nation, or the security of the nation.”

There are no advertised scholarship applications for non-Muslims.

Figures obtained from the Office of International Affairs show that 83 percent of Saudi Arabian students at PSU received scholarship funding from the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission in fall 2015.

SACM is an arm of the MOE, which provides support and assistance to students studying in the United States. It has the unilateral authority to revoke funding for any Saudi Arabian national.

Both Mutab and Faisal said the large presence of Saudi Arabian students on state scholarships sometimes creates an environment of ideological conformity given the precepts of the program.

When Mutab first attended PSU, he attempted to find a supportive community within the Saudi Student Association but soon found conflicts of interests.

“They are connected to SACM,” Mutab said. “Their priority is to promote the interests and image of the state.”

The SSA at PSU, which also goes by the name Saudi Student Club, is listed on SACM’s website. The group’s written mission statement says it is “NOT representing any political or religious views,” but this is contradicted by pro-regime commentary and explicitly religious posts in Arabic on the group’s official social media accounts.

Faris Alhanaya, president of the club for the 2015–16 academic year, confirmed to the Vanguard that the group received funding from SACM but denies any allegations that the group is intolerant of different political and religious views.

“During my presidency we had celebrated four events and we have never asked certain people to join, but our celebrations were always open to anyone,” Alhanaya said.

Mutab added that some Saudi Arabian students are motivated to police the thoughts and behaviors of their peers due to their own family connections to the Saudi Arabian government. “They benefit from the regime, so naturally they are very protective of it,” Mutab said. According to the International Monetary Fund, around 86 percent of Saudi Arabians are employed in the government sector as of 2013.

Asylum

The insecurities that come with being a closeted atheist on a state-funded scholarship are not unwarranted, Faisal explained. Earlier this year, Haifa Alshamrani, a Saudi Arabian woman studying pre-med at the University of Glasgow, had her scholarship revoked.

Alshamrani, who is ex-Muslim, alleges that the Saudi Arabian government ended her scholarship as punishment for her husband’s refusal to support efforts to build a local Wahhabi mosque during his time as chairman of the Saudi student organization. “He was only supposed to assist in academic issues as declared [on the club elections page],” Alshamrani said.

Fearing charges of apostasy upon return to Saudi Arabia, Alshamrani and her husband have filed asylum claims in the United Kingdom.

Mutab considered seeking asylum last year but gave up after finding the legal process confounding and risky given that a right to stay is not guaranteed. Faisal and Noora do not have plans to seek asylum at the moment. They said that they cannot cope with the prospect of abandoning family and friends for an uncertain future.

According to international and U.S. law, foreign nationals can seek refuge if they can establish that they were “persecuted or fear persecution due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.”

Although refugee eligibility appears broad, qualifying at the individual level is often difficult. “It’s not just about wanting to apply for asylum,” said Shalini Vivek, staff attorney at PSU’s Student Legal Services. “They have to make sure they actually even qualify for it.”

The office employs two part-time contract immigration attorneys who are available by appointment for counsel. Their area of expertise includes asylum, Vivek said.

Vivek added that the Office of International Student and Scholar Services sometimes reaches out to SLS to put on presentations that cover asylum-related issues for students from specific countries. However, “[Representatives from the OISSS] haven’t advised us on asylum for Saudi Arabian students,” Vivek said.

The OIA oversees all matters related to the specific needs of international students but currently lacks protocol for providing recourse for students who face possible prosecution in their home country for “thought crimes” conducted while studying at PSU.

“If a student presented themselves to us with this sort of problem, we would make every attempt to support them,” said Christina Luther, director of OISSS, an office within the OIA. When asked for details, Luther said, “I really can’t tell you what kind of support we would offer a student with specifically this type of situation because I have not encountered it before.”

Luther explained that the office doesn’t have the capacity for that level of specificity. However, she stressed that this does not mean they are unavailable to help students navigate unique crises.

The Catch-22 situation is a reality that all three interview subjects face. They remain silent in fears that escalation could exacerbate problems, while university administration is only able to provide general support at this time.

The essentialist paradigm

In a final plea, Mutab, Faisal and Noora asked that the local community not presume that those with Muslim backgrounds prefer or need different treatment. They likened the experience to encounters with the religious police, or “mutaween,” of Saudi Arabia’s Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice. The committee is tasked with enforcing conservative Islamic principles on the population.

“The assumption that every Arab is a Muslim creates a barrier between myself and other students,” Faisal said. “I wouldn’t get invited to social events based solely on the assumption that I would hate a mixed-sex environment.”

Until this year, the mutaween were allowed to harass and detain social offenders. Offenses can be as simple as violating Islamic dress codes or mixing with the opposite sex.

“Islamic beliefs would always be defended by non-Muslims around me just so that my feelings aren’t hurt,” Faisal said. “This is mostly a social problem, but in an academic space it’s really troublesome.”

Manea argues that the postcolonial and postmodernist discourse often found in Western academe homogenizes and essentializes certain perceived features of minority groups.

“The ‘essentialist paradigm’ uses a prism that reduces minorities of different national and cultural backgrounds to their religious identity,” Manea said. “Consider the person who is called a Muslim, ‘perceived’ as a Muslim and ‘treated’ as a Muslim, despite the fact that this person may not be religious at all or may prefer to be identified by his or her nationality.”

Through his work as president of EXMNA, Syed recommends that universities better promote and foster secular cultural groups. “Muslim and ex-Muslim students often already have enough pressure exerted on them by family and other students to act in a religious fashion,” Syed said.

PSU’s Cultural Resource Center has a dedicated space in the Multicultural Student Center to focus on programs for multiracial, Middle Eastern, North African and international student populations.

In February of this year, PSU hosted a campus-wide teach-in event on Islamophobia. “[The teach-in was] organized in response to a rise in anti-Islamic actions and rhetoric throughout the country, including the PSU campus,” President Wim Wiewel said in an email sent to every student.

“Islamophobia is a form of racism,” said Dana Ghazi, student body president for the 2015–16 academic year. “It’s not different than any other racism that’s operating in this community.”

Mutab, Faisal and Noora expressed discomfort with some Islamophobia awareness campaigns. They explained that even though they are sometimes the victims of anti-Muslim bias, Islamophobia can be a problematic concept at the ontological level because it does not separate criticism of ideology and religious practice from that of Muslim people. In a Saudi Arabian context where religion and state are intertwined, they have been accused of being Islamophobic when they spoke out online against state practices.

Signs of progress in the Kingdom

Despite the challenges of living in the shadow of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Mutab and Faisal are hopeful about the future. “The new generation of Saudis who studied abroad are capable of improving things back home,” Mutab said.

Faisal said that while the growth of liberalism is slow in Saudi Arabia, it is happening and issues like women’s rights and free speech have gained international and domestic attention. This year, several high-profile social media campaigns have focused on women’s rights in the country. Saudi Arabia has some of the highest per-capita usage of social media in the world according to the Dubai School of Government.

Most recently, the Arabic language hashtag which translates to “Saudi women demand the end of guardianship,” became popular on social media after HRW published a scathing report on the state of women’s rights in the country. The report details how the guardianship system limits women’s mobility and access to education, housing, healthcare and employment.

In response to calls to end the guardianship system, Abdul Aziz al Sheikh, the Grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia, said in the Arabic-language Okaz newspaper that the campaign is a “crime against Islam and Saudi Arabian society.” Al Sheikh is the top religious authority in Saudi Arabia. He advocates for the guardianship system to remain.

In contrast to Mutab and Faisal, Noora has dimmer prospects about the future. “The experience of being a woman in Saudi Arabia today makes me hopeless,” Noora said. “Changes like voting at municipal elections are meaningless gestures.”

Late last year, Saudi Arabia introduced internationally lauded reforms that allowed women to vote for the first time at local elections. However, the elected officials have limited political power in the monarchical state. “I yearn to be treated and seen as an equal human being. The Shari’a of my country prevents change,” Noora said.

In spite of their differences over predictions on the direction of the Kingdom, Mutab, Faisal and Noora believe that secularization is a key in liberalizing Saudi Arabian society and policies toward a democratic future. Meanwhile, their views remain in the protective shadow of anonymity.

The Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia in Washington, D.C. and SACM did not respond for comment on issues raised in this article.

Editor’s note: The Vanguard is committed to free speech and serving its diverse audience. This includes people of all faiths and non-faiths. We stand unequivocally for the rights and protection of all people based on religion, beliefs, gender, sexual orientation, national origin and race. Students who feel they are the victims of prejudice or harassment can find support at the PSU Office of Equity and Compliance. Online comments which threaten or insult individuals or groups of people will not be tolerated. We encourage civil discourse.

If your religion is Salafism/Wahabism to leave it is a duty!

Nice article, its really great when Muslims and ex-Muslims can talk about Islam frankly, more people in the west should listen to these voices.

In recent years the US media has really gone nuts pushing the Islamophobia narrative on the American people; and a lot of people believe it, the teach-ins, the political correctness surrounding Islam etc. all this has done is silence critics of Islam.

A phobia is an irrational fear of something, when 4 out of 10 Muslims report (report being the key word) that they believe apostates should be killed, it is not irrational to be wary of Islam or its followers. Clearly for those mentioned in this article it is a very real and active threat they face.

Sorry, Daniel, but Islamophobia is rampant in the West. One’s stand on apostasy or any other religious issue should not give you the excuse or the moral authority to hate others. Have you heard of the cruel assassination of Shaddy Barakat, Yusor Mohammad Abu-Salha, and Razan Mohammad Abu-Salha in Chapel Hill, NC, or the Imam and his assistant in NY? It is all because of this type of discourse that some condone in the name of criticism. Islamophobia is no different from Fascism or Nazism. It is an ideology based on hate and intolerance of the religious values of others.

Javid,

Islamophobia is not rampant in the west, this term was reinvigorated here in the west after the 9/11 attacks by those who want to silence legitimate criticisms of Islam. The poll I referred to in my original post was a Pew poll conducted in a number of Muslim majority nations in 2011. Here in America 26% of young Muslims reported in a 2007 Pew poll that they believed the use of suicide bombings is a justified practice. If you want to educate yourself on what Muslims actually think and believe around the world I suggest you checkout the source below.

Source: http://www.thereligionofpeace.com/pages/articles/opinion-polls.aspx

*note: if you don’t like the source then use the vast list of reputable polls cited within. These polls are reputable and self reported by Muslims all around the world on a wide variety of issues.

This is an incredibly telling statement by you: “One’s stand on apostasy or any other religious issue should not give you the excuse or the moral authority to hate others.”

You are using accusatory language and accusing me of Islamophobia and ‘hate’ for pointing out that legitimate criticism of Islam exists and in the same sentence you included the taking of someones life for their leaving of a religion (apostasy) with the terms ‘moral authority’ and ‘hate’ – in the same sentence; this is incredibly ironic. I cant think of anything more hateful than to kill someone, especially only because they left a particular religion.

According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports: Hate Crime Statistics, 2014, there were 1,140 victims of anti-religious hate crimes in the U.S. in 2014. “Of the 1,140 victims of anti-religious hate crimes: 56.8 percent [56.8%] were victims of crimes motivated by their offenders’ anti-Jewish bias.” That amounts to approximately 647.52 instances where Jewish individuals, businesses or institutions were targeted.

A mere “16.1 percent [16.1%] were victims of anti-Islamic (Muslim) bias,” amounting to approximately 183.54 instances where Muslim individuals, businesses or institutions were targeted.

To make this data clear – there were roughly 184 instances of Islamophobic behavior that actually lead to crimes against Muslims in 2014. American Muslims make up roughly 3.3 million of the current US population as of 2016. This data shows that a mere 0.0056% of Muslims actually had a crime committed against them based only on the fact that they are followers of Islam.

Listing off specific examples of individuals killed does not provide evidence of an overarching theme or history of Islamophobia here in the US.

I’m wondering if you are being insincere here because lumping Fascism and Nazism together with Islamophobia is absolutely laughable. Go read up on what those words actually mean.

The facts simply do not support what you are saying; I suspect you simply want to shut down all debate and criticism of Islam, which is exactly what parts of this very article and my original comment were about.

@Daniel I am an apostate from Islam and you have the totally wrong idea about us. Yes, we do speak out against Islamic teachings but many of us still despise Islamophobia (although I prefer the term “anti-Muslim bigotry”). Just because we think that Islam isn’t true and that Muhammad was a fraud doesn’t mean that we condone mindsets which propagate hatred and demonise our families and friends. Islamism is a problem which needs to be tackled but the same applies to anti-Muslim bigotry. There are groups in my country which incite hatred and violence towards Muslims, making people like my mum less safe when they leave their homes, I loathe such people every bit as much as hardline Islamists.

If you are one of those people then yu are not welcome among us.

Wabzi Shill,

I don’t see how much of what you said even pertains to what I wrote; you accused me of Islamaphobia (which I fundamentally disagree with the word even being a word that actually means anything, we cant police peoples thoughts now can we?) which is wholly wrong of you to do. You are simply making accusations when I said absolutely nothing that could even be construed as such.

Nothing is off limits from criticism and Islam is no different; and as an apostate I find it shocking that you do not understand this – the fundamental core of what it means to live in a free society.

@Daniel where did I suggest that Islam was “off limits to criticism” and where did I accuse you of Islamophobia? I expressed contempt for those who promote hatred towards Muslims as people, and said that if you are one of these people then you are an enemy, not an ally. The people who are closest to many of us (family and childhood friends) are Muslims. Criticising Islam =/ hating and demonising Muslims; one is acceptable, the other is not. And if you cannot distinguish between the two then you have a problem.

Wabzi Shill,

I guess I fail to see what your point is as it pertains to what I wrote. You didn’t directly accuse me of Islamophobia but it was explicitly implied because what you wrote was wholly incoherent when compared to what I said other than a challenge me on my personal beliefs ex. ‘If you are one of those people then you are not welcome among us.” I agree we shouldn’t hate Muslims simply because they are Muslim, we can however look at the data on what Muslims think around the world and draw clear conclusions from that.

Also,

This statement: ” Criticising Islam =/ hating and demonising Muslims; one is acceptable, the other is not. And if you cannot distinguish between the two then you have a problem.”

Clearly shows that you should take your own advice.

And I meant what I said: if you are one of those people then you are not welcome among us. I didn’t say that you were one of them but did make an inference that you could be based on your using a link from a far-right website. Maryam Namazie wrote a brilliant article titled “The Far-Right and Islamism are Two Sides of The Same Coin” based on a report put together by One Law For All. It focuses on the likes of Robert Spencer and Pamela Gellar who claim to be mere critics of Islam, however there are several examples of them demonising and inciting hatred (occasionally violence) towards Muslims. This is because the Far-Right likes to rear its ugly head among ex-Muslims, thinking that we will endorse their despicable views just because we criticise and reject Islam. So some of us do get understandably wary of people who use their websites as a source.

“Clearly shows that you should take your own advice.”

In what sense? You have yet to show me where I said that Islam was beyond criticism, which indicates that you may very well have this problem that I was referring to.

Wabzi Shill,

I made a note with the website when I linked it, you must have missed it.

You should clearly take your own advice because it is very apparent to me and anybody reading this with at least a decent understand of the English language that you cannot tell the difference between criticism and hate speech.

I don’t care about your feelings, I care about facts. You have repeatedly made assumptions about me as a person instead of addressing the merits of my arguments.

I will no longer be responding to you.

@Daniel if you like facts then there is some very detailed criticism of that website and the way by which it compiles its stats from another website that I used to visit (not a fan of LW anymore but this criticism in particular is very relevant). Its criterea for what constitutes a terror attack, for an instance is problematic, and it is a website that lists attacks by separatist and nationalist which happened in Muslim-majority countries as “Islamic terror attacks”:

The clear visual intent of this “Islamic terrorism ticker” is to provoke an emotive fear and anxiety of a global, monolithic, totalitarian Islam (read: Muslims), that is waging terror everywhere through thousands upon thousands of unmitigated and random attacks. On TROP the “terror ticker” serves as ammunition for the site’s stated missionary proposition of portraying “Islam” as “the world’s worst religion.” It also aids in the attempt to tie terrorism to Islam.

Even a cursory glance at TROP’s list of so-called “Islamic terrorist attacks” reveals it to be nothing more than a deeply biased, propagandistic spin-job that conflates: real terrorist attacks, (semi)religious/culturally motivated crimes, attacks on military personnel and attacks by secular groups with no ideological basis in Islam — all in theaters of occupation, civil war and separatist conflict.

http://www.loonwatch.com/2012/07/thereligionofpeace-com-working-to-streamline-the-american-empires-war-on-terror/

I couldn’t care less whether or not you reply, I have simply made it a point to stand up to anyone who appears like they could be sympathetic to the far-right and tries to associate their views with those of ex-Muslims; they do more harm to our movement than good.

Wabzi Shill : It is important to qualify hatred of an IDEA as totally different & not the same thing as hatred of people who happen to believe in that idea.

I hate Islam because of what it’s books say it wants to do to me as a non-believer and what it’s history has been, which has been caused by it’s extremist adherents. I do NOT feel hatred towards the millions of cultural Muslims who were born into the system and are ‘Muslims’ thru no fault of their own !!! I can talk about this and recognize that there may be a few Muslims who want to chop off my head because of how I feel, but I know that most will not do that. We mostly tolerate each others religious ideas because we do not threaten other people for their faith. That in my view is the only way to conduct your life, as you do not know what is in the other person’s heart.

By the way, nearly half of Donald Trump’s supporters hold racist views towards Black people. Does that justify demonising and spreading hatred towards all of his supporters?

Wabzi Shill,

If you do not provide valid evidence of that claim it is just your personal opinion – which you are entitled to.

There is your evidence:

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-race-idUSKCN0ZE2SW

Wabzi Shill,

Finally you actually provide some real information other than your personal opinion. Even though this is a deflection away from what I wrote and what this article is even about, I will at least somewhat indulge you this time.

when 13% of the American population (African-Americans, and really its more like 5 or 6 percent; the young black male population) commit nearly half of all murders in the United States – it makes sense that they would be viewed by people as more violent, because – statistically they are! I suggest you look at the FBI crime statistics for the United States so you can gain a better understanding on the subject. We could go into the reason why this is – gangs, structural problems within the black community, black culture etc. but I will not be addressing this topic any further as it is not part of the original article.

The article you cited also places Democrats not far behind Republicans in a lot of the views that article and poll addresses. We know that blacks and minorities in general have traditionally overwhelmingly voted for democrats and are democrats themselves which would of course skew the poll.

Remember this – facts do not care about your feelings or opinions, they are facts after all. I suggest you educate yourself on these subjects further so you can actually provide detailed, intelligent, meaningful arguments.

@Daniel for some reason I cannot reply directly to your comment but Black people are responsible for less war, terrorism and colonisation than White people and several other races. Violence does not only come in the form of gang-related crime. And what is your justification for the rest of their views such as the view that Black people are less intelligent than White people?

Sure, the polls are reliable when you want to tar Muslims with the same brush but are skewed when applied to Trump supporters. That right there is an “intelligent, meaningful argument”, lol! Got to love impartiality.

Wabzi Shill,

I provided facts and evidence to back my claims, you provided emotion and opinion; the article and poll you provided I gave at least a cursory explanation for (backed by facts; which I’m tired of handing you, go find them yourself) which is more than you have added throughout this entire back and forth.

As a current political science student at Portland State University I find it incredibly troubling that students with your level of acuity in reading, writing, reasoning and logic will be allowed to graduate with degrees this year and in the future.

I will no longer be responding to this topic because it is clearly pointless.

@Daniel

And I provided evidence that a disturbing percentage of Trump supporters believe Black people to be less intelligent than White people and lazier. If the fact that this is the case and you can’t defend offends you to the point that you cannot finish this discussion then it is you who is arguing on the basis of emotion. I made the analogy between Muslims and Trump supporters because you thought that it was fine to generalise Muslims on the basis of certain stats, but when the same method of generalisation applies to a group that you appear to approve of, somehow it is no longer valid.

Thank you for your concern but I graduated with a Master’s degree this year. What’s more concerning is that people with bigoted views are attending university and interacting with people who they view as violent and unintelligent due to their race, or at least think that their is nothing wrong with stereotyping them in such a way.

By the way: it’s not a deflection since I was applying the argument that it’s OK to use stats to generalise an entire group (Muslims) to another group (Trump supporters).

I am a Muslim n a woman. Where I come from I am free to vote @21 yrs old, drive n attend secular education and mingle with friends of all religions backgrd n races. My late dad never differentiated between boys n girls. Both my brothers have to do housework like the girls to help out my mom. We were raised as practising Muslim. But never my late dad disallowed any of the daughters to go out by ourselves. We did have curfews(which I still practise with my now 3 teenagers kids- boys or girls) on when to be home. I dont wear the hijab too as its not compulsory. Just so long one dress modestly and to always respect others. That was what my late dad thought us. Islam is a way of life. We hv been instilled since young to be nice to our neighbours of different races and religions. To live in harmony. That is Islam. God Almighty is merciful and forever forgiving and loving. At the end of the day; its between you and Allah when u die.

A brave article. Great job!

Great article, thank you for sharing! And thank you to the brave ex-muslims for bringing out the truth!

Sign this petition to get Saudis kicked out of UN Human Rights Council: https://www.change.org/p/un-human-rights-council-expel-saudi-arabia?recruiter=26992994&utm_source=share_petition&utm_medium=copylink

Both Muslim reformers and apostates should be granted a green card so they don’t have to go back to their dungeon states.

A clean energy revolution would bankrupt Saudi Arabia and other Islamist regimes reliant on oil and force them to liberalize and become productive countries.

Islamic world dissidents should get a special passport from the US so they can come and go from America as they please depending on how dangerous the situation is at home and be able to make a living here. We need a new progressive liberal left to replace the morally slimy regressive left that turns its back on Muslim-world liberals and even will apologize for Islamism and make alliances with it. The Euston Manifesto, available on line, delineates an orientation for a more democratic, less oedipalist left that will oppose all fascism whether of the West or the Third World

A list serve devoted to this matter is the Euston USA list serve.