Over the past few weeks news outlets have been flooded with dire reports of brewing

conflict between North and South Korea.

Kim Jong-un, the supreme leader of North Korea, has threatened South Korea repeatedly as North Korea seemingly prepares for a missile launch. But are South Koreans actually concerned about the threats, or have they grown so used to them that they’ve learned to ignore them?

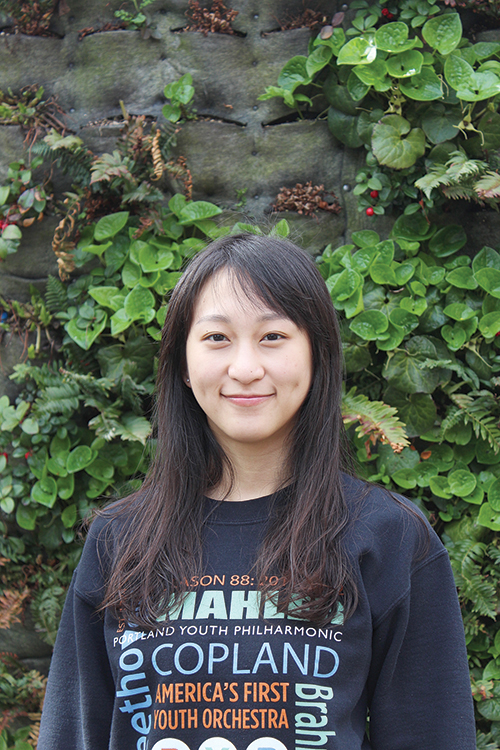

Ran Yoon, a Portland State junior in community development, said she’s not very concerned. “I don’t really worry that much, because I don’t believe the war will happen really easily.”

Yoon pointed to the fact that South Korean news outlets aren’t featuring as many stories about North Korea’s threats as news outlets in other countries are. Yoon thinks the rest of the world is more worried than South Korea is.

She said her family’s only concern is that her brother is due to start his mandatory two years of military service in August.

Dr. Bruce Gilley, an associate professor of political science in the Mark O. Hatfield School of Government who specializes in Asian politics, also downplayed the danger to South Korea.

Gilley said that between South Korea’s superior military power and the fact that great powers like the U.S. and China are on South Korea’s side, the risk to them is low.

“The real stake here is not South Korea’s security, it’s North Korea’s future,” Gilley said, adding that any conflict between North and South Korea would be extremely short.

If North Korea were to make a strike against South Korea, Gilley said, “China would be the first to condemn it.” He added that, contrary to some pundits’ fears, the likelihood of U.S. involvement in a possible conflict is low.

Bona Kim, a junior in accounting, summarized the mood of the PSU Korean community as “a little bit of both concern and thinking nothing will happen.”

While some members of the community are concerned for their family and friends back in Korea, Kim said she doesn’t think North Korea will act on their threats and is perhaps posturing so the global community will give them gifts in order to appease them.

“If [North Korea] starts something, they would have so much more to lose than other countries that are involved to this,” Kim said, adding that while she can’t see North Korea actually acting on the threats, they still make her uneasy.

“I feel like most people here feel that way—that nothing will actually happen. But we still, for some reason, talk about it a lot.”

Kim said this may be because to the PSU Korean community there’s a big difference between a short conflict and no conflict at all.

South Korea requires all men to complete two years of active military service, after which they become reserve troops. In the event of a conflict, many Korean students at PSU would be called back to Korea to fight.

“For being Korean and being at this age where a lot of guys are supposed to be in the army, that’s something we’re really concerned about,” Kim said. “Recently the Korean government sent out notifications to all the Korean men telling them that if something were to happen this is where [they] would be placed and this is what [they] would do.”

One of Kim’s friends was told he would be serving on the front lines, while another would be “grabbing uniforms off of dead soldiers and then washing them so new people could use them,” she said.

“When we’re analyzing things and thinking about military strategy, we’re like, ‘Oh, South Korea will definitely win.’ But it might be one of my friends who is one of the people who dies in the little conflict.”