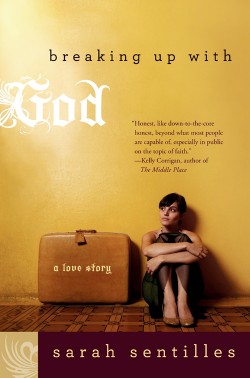

Religious scholar Sarah Sentilles will be holding a workshop at Portland State Thursday, Feb. 16, that focuses on “Seeing Other People,” the final chapter of her latest book, Breaking Up with God: A Love Story.

Losing my religion

Religious scholar Sarah Sentilles will be holding a workshop at Portland State Thursday, Feb. 16, that focuses on “Seeing Other People,” the final chapter of her latest book, Breaking Up with God: A Love Story.

Sentilles, who was raised Catholic, was on her way to becoming a priest in the Episcopalian sect when her beliefs changed. In her book, she recounts her personal journey of faith, explores the courage and honesty that comes from questioning one’s beliefs and shares what it means to come to terms with the loss of a lifelong love: God.

In “Seeing Other People,” Sentilles examines world events as well as events in her own life surrounding this ultimate “break up,” and speaks to the value of humanity that shaped her new worldview.

In an exclusive interview with the Vanguard, Sentilles, who holds a master’s degree and doctorate from Harvard, speaks about her book, her faith and where her spiritual journey will take her next.

Vanguard: What is going to be the focus of your workshop [at Portland State]?

Sarah Sentilles: I’ll be talking about the last chapter of my book. It’s my attempt to start moving toward what comes next for me after institutional religion.

VG: When you say you broke up with God, is that your institutional understanding of religion and God?

SS: It was primarily that.

VG: In your chapter, it seems like you still believe in God, but your relationship changed.

SS: I think I broke up with a particular understanding of God. I identify as an agnostic. I won’t say there’s no God because there’s really no way humans beings can know. The biggest influence on my thoughts is a theologian named Gordon Kaufman, who I dedicated my book to. He argues that asking whether or not God exists is the wrong question. God is out in the world, in the language that we speak. The word “God” is there, doing all kinds of work, good things and bad things. I view it as my role as a theologian to hold people accountable for the effects of their understandings of God.

VG: If God does exist, and you say he is out there in the world, in the language that we use, are we obligated to worship Him?

SS: I wouldn’t call God a “he,” first of all. The way I think about God, I have the concept from my mentor Gordon Kaufman…which is the notion of “serendipitous creativity.” The kind of God I want to believe in wouldn’t care whether I worship that God. I think it’s a really small concept to think that God needs our attention to thrive in some way. The kind of God I would want to believe in would want me to be taking care of other human beings and the earth. It’s always struck me as funny that people think whether you go to heaven depends on whether you believe, or have accepted a version of God. It seems like a very petty version, that you die and God looks into your mind to see if he had a place in there. It seems a very small and narrow version.

VG: In the chapter, you speak of being “unlovable” and of your own self-doubt. Do you think that pushed you into depending on religion in your own life?

SS: In one way, yes, my sense of longing to be loved and not loving myself enough made me look outside myself for someone who would love me, and sometimes that was God and sometimes that was romantic relationships. But I also think that the way that God was taught to me through the church in which I grew up, as this man that was watching me, waiting for me to get in trouble and punish me, or would love me if I was good, also contributed to my sense of not being good enough,

VG: At the beginning of the chapter, you talk about your grandfather and his battle with Alzheimer’s. I was wondering if part of the changing relationships we have with God has something to do with scientific understanding, and how that’s really changed the way we view religion?

SS: The funny thing is, the more I learn about science, the more full of wonder the world seems, and the more mysterious the world seems for me. If anything, an increasing understanding of how science works has made me have a deeper appreciation for the magic that’s in the world. One of the things people say to me all the time when they find out I identify as an agnostic is, “Don’t you need something bigger then yourself?” and I always feel, “Haven’t you been outside?” All you have to do is look at the stars, or how small the earth is, or the fact that there are so many human beings. It seems there are a lot of things and a lot of energy that’s bigger than we are that can give our lives meaning and be an ethical foundation.

VG: Despite your break up with God, do you still see value in reading the Bible and seeing it as a way to learn and teach?

SS: I think that the Bible tells amazing stories about what it means to be a human being trying to find meaning in the world. I think the trouble comes when we try to make it literal, which to me really flattens the value that could be in there.

VG: Identifying as agnostic, do you think there was social pressure to come up with a label for yourself?

SS: People always said to me, “OK, so you don’t call yourself Christian. So what are you now?” I choose agnostic for ethical reasons, because I feel like one of the most important ethical statements we can say is “I don’t know.” I think certainty is what gets us into trouble in terms of war and violence against other human beings and violence against animals. I choose agnostic because it did work ethically for me, but mostly because people kept asking, “What are you?” It was a way to stop people from asking me that.

VG: In your experience with California’s Prop 8 proponents that you discuss in the chapter, I wasn’t sure if you’re blaming God or the people themselves.

SS: I was blaming people for using a certain perception of God to do their own work. I am not blaming any God outside of peoples’ construction of God. I think of God as how we talk about God. It seemed the people around Proposition 8, people that are anti-civil rights, are constructing a particular version of God that they need, and having that version do the work they want to do in the world. They say they take the Bible literally, for example, but they don’t. They only take certain versions and follow certain rules. A lot of people don’t eat kosher. They stand next to menstruating women. They don’t think the death penalty is a good punishment for adultery. All of those things are right next to those other things [in the Bible].

VG: You speak of the torture in Iraqi and U.S. prisons, and the rapes that happened in the eastern Congo, and you hear a lot of people asking, “If God exists, how can he allow these things happen?” Was this part of questioning your God?

SS: It became ethically untenable for me to believe in a God that could intervene in human affairs and chose not to. I just can’t square that version of God with that world around me. You just have to see the newspaper to see so much human suffering. People believe in versions of God where God can’t intervene but can be present in the suffering, and that is a beautiful alternative. The way that I was taught is that God can intervene in human history, and to me, if God can do that and is choosing not to, then that’s not a God I can believe in.

VG: Since the publication of your book, have any of your beliefs changed?

SS: I started to call myself agnostic, that’s a change. And I am starting to open up to the possibility of going to Quaker meetings. It seems to me that that would be the only place where I could go and feel a sense of community. I am longing for a sense of community.