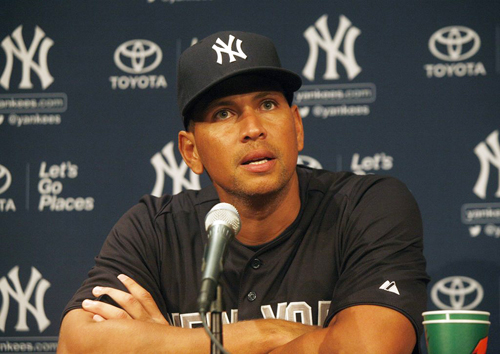

Time passes slowly in baseball. There is no game clock and no final buzzer; baseball moves through a 162-game season at its own pace, often laboriously, working toward the final out that won’t come until the players on the field manage to orchestrate it. A single game can take up an entire afternoon—a couple hundred can seem like a lifetime. For Alex Rodriguez, 200 games may represent exactly that.

On Monday, Major League Baseball handed down its ruling against 13 players for violating the league’s policy against performing-enhancing drug use. The announcement came after Ryan Braun, the 2011 National League MVP, had previously been given a 65-game suspension.

While 12 of the players received 50-game bans, Rodriguez’s sentence was the most severe of the group, stretching through the end of the 2014 season—the equivalent of 211 games. The league opted not to exercise its “best interest of baseball” clause, which would have allowed them to suspend him for life. But Rodriguez’s suspension is the longest in the history of the game outside of a lifetime ban, and for a 38-year-old coming off a serious rehab stint in the offseason it could spell the end of a career.

Rodriguez still has the right to appeal the ruling, an opportunity not given to the other 12 other players on the list, which means that there is a chance the suspension could be reduced. He will also be allowed to play until the appeal is heard and made his season debut for New York on Monday. If the ruling is upheld, though, Rodriguez will forfeit about a third of the $95 million left on his contract through the 2017 season.

Rodriguez and Braun weren’t the only big names on the the list, either: 2013 all-stars Jhonny Peralta, Nelson Cruz and Everth Cabrera were among the 12 players who got 50-game suspensions. It has been an unprecedented week for Major League Baseball and concludes months of rumors, speculation and intrigue surrounding the South Florida anti-aging clinic Biogenesis and its high-profile client list. The verdicts set a new precedent in MLB commissioner Bud Selig’s ongoing quest to rid the league of PEDs, demonstrating his renewed commitment to clean up a sport that has long been a haven for drug use.

For many of the players involved, the days ahead will mark the beginning of the long and difficult process of repairing tarnished public images among fans and sponsors (Braun saw his agreement with Nike voided following the announcement of the ruling). For Rodriguez, a player long expected to go down as one of the best in the history of the sport, it is likely far too late.

In 2009, when revelations first surfaced that the Yankee third baseman had tested positive for PEDs while playing for the Texas Rangers in 2003, they were met with flat denials from Rodriguez and his camp; only after immense pressure from the media and unavoidably damning evidence from the league’s investigation did he confirm his guilt in an interview on ESPN. Following the revelation, Rodriguez painted himself as an outspoken advocate against PEDs, going so far as to announce plans to become a spokesperson for the Taylor Hooton Foundation, an organization established to educate people on the dangers of PED use.

For years, Rodriguez’s testimony has been consistent. He claimed that his history with PEDs did not extend beyond 2003, a period of his life that was characterized by naivete and youthful foolishness that a wiser and more mature Rodriguez has long since left behind. But as Monday’s ruling made clear, foolishness is not confined to the young, and the only gullibility that could be attributed to Rodriguez is that which allowed him to believe his flippant disregard for baseball’s PED policy would never catch up to him. Rodriguez’s story is not particularly unique in this era of professional sports. It is, however, an important one to remember.