How does anyone first discover that they’re a film lover? It has to be tied to childhood just like everything else, right? I remember watching John Huston’s Annie when I was little, especially the part when Daddy Warbucks takes her to the movie theater for the first time at Radio City Music Hall, no less.

Memoirs of a teenage cinephile

[portfolio_slideshow id=50496]

How does anyone first discover that they’re a film lover? It has to be tied to childhood just like everything else, right? I remember watching John Huston’s Annie when I was little, especially the part when Daddy Warbucks takes her to the movie theater for the first time at Radio City Music Hall, no less.

It’s the most exciting extravaganza you can imagine, with a fabulous musical number: Welcome to the movies! Welcome to the stars! Welcome to this grand illusion! All of it’s yours! Right through these doors!

(Trivia: They see Camille, which came out in 1936, even though Annie is supposed to take place in 1933. And both films feature the work of editor Margaret Booth.)

I like to think that going to the movies when you’re a kid is a little bit like that scene. And, to me, being a film geek means you never really lose that feeling. That’s the only definition I can settle on.

In my case, official film geekdom began in junior high, when my movie-watching habits became so obsessive it’s kind of embarrassing. It seems kind of fitting that I associate puberty with the discovery of some of my favorite directors.

I went through a phase in the seventh grade where I woke up at 4 a.m. every morning to watch a movie before school, because I hated school and I just couldn’t stand getting out of bed and then having to be there. I needed a buffer, something to shield me from real life—and isn’t that what films are all about? Red lights holler deep depression! What do we care? Movies are there!

That was when I started devouring everything. I watched classics like Goodfellas, Blue Velvet and The Untouchables. I saw Raiders of the Lost Ark for the first time. And I developed my taste.

I discovered Quentin Tarantino and Gus Van Sant, Richard Linklater and Danny Boyle. I found something I liked and watched it over and over and over and over again. I have so many memories of rewinding VHS tapes to the beginning so I could watch them one more time.

Did you know the first three movies released on VHS in the United States, in 1977, were The Sound of Music, Patton and M*A*S*H? They each cost around $60 at the time. By contrast, Twister was released on DVD in 1997 and cost about as much as it would today.

What about now? I think there’s a very important distinction between being a film geek and being a film snob. Don’t get me wrong: For a long time I thought my taste was better than everyone else’s. I was a champion of independent film and looked down on anyone who didn’t like The Royal Tenenbaums but was really excited by You’ve Got Mail.

But, seriously, don’t do that. No matter what you’re a geek about, it shouldn’t be a competition.

(Trivia: Originally, The Royal Tenenbaums’ Richie and Margot were intended to be blood siblings, rather than Margot being adopted like she was in the final version. Director Wes Anderson knew a kid in the fourth grade who was in love with his own sister. I love DVD commentaries.)

If you really love films, you love the ones that mean something to you. Each one represents something you learned or something you related to or something that affirms your beliefs and values, even the silly ones.

I no longer believe in the hipster-esque notion that your taste defines you. Great films, like great music or literature, exist to let you know you’re not alone. They say the things you’ve always wanted to say but never found the words for.

The films that do that for you might be very different from the films that do it for other people. I remind myself of this every time someone tells me that Tree of Life changed their life. It’s still hard.

I suppose being a film geek is in my blood. My grandmother is in her 70s and still watches at least two films every weekend, and every conversation we have begins with, “What have you seen lately?”

It just goes to show that film lovers don’t look a certain way or follow a certain set of rules. She may not have lined up as quickly for Django Unchained as I did, but she can tell you more about movies than most people I know.

My grandmother was born in 1934, the year Capra’s It Happened One Night swept the major categories at the Oscars and Greta Garbo starred in The Painted Veil. Two years later she starred in Camille.

Welcome to the movies, all over again.

10 underrated films by celebrated directors:

Big Fish, Tim Burton, 2003

Burton is much more famous for the unique macabre worlds of classics like Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands and his more recent collaborations with Johnny Depp such as Alice in Wonderland and Sweeney Todd. But Big Fish, the poignant and whimsical tall tale of a man trying to connect with his dying father, is arguably his most human creation.

The Abyss, James Cameron, 1989

Everybody loves Titanic, but I still maintain James Cameron was a better director in the 1980s. The Abyss tells the story of the motley crew of an underwater oil rig and the deep-sea aliens they discover. It gets its thrills from the unknown since this was long before big-budget special effects were in the picture.

The Age of Innocence, Martin Scorsese, 1993

Everyone thought Hugo was the biggest departure for the director of Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Casino and a bunch more films we all love. But his poetically detailed adaptation of Edith Wharton’s novel about Victorian society in New York City might be an even greater leap, and a better one.

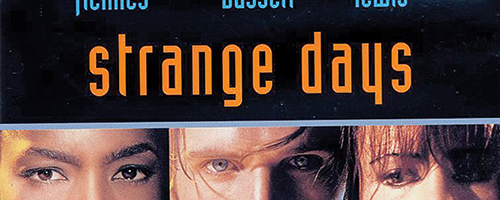

Strange Days, Kathryn Bigelow, 1995

It definitely lacks the realism of The Hurt Locker or Zero Dark Thirty, but Bigelow’s unique celluloid tale of a virtual-reality hustler at the turn of the millennium is part campy, part menacing. It deserves to be a cult classic. Plus, the soundtrack is amazing.

A Dangerous Method, David Cronenberg, 2011

Cronenberg, the so-called master of venereal horror, is celebrated for a host of films, from Videodrome and The Fly right up to A History of Violence. But his undeniably talky history of the relationship between Freud and Jung looks at weird from a new perspective. It’s one of my favorite films and deserved more love than it got.

Sunshine, Danny Boyle, 2007

Boyle won an Oscar for Slumdog Millionaire, the only one of his movies I don’t love. A year before, he made this stunningly bleak sci-fi horror gem about a crew trying to reignite our dying sun. It’s both frightening and beautiful, something he does exceptionally well.

Romancing the Stone, Robert Zemeckis, 1984

We love Zemeckis mostly for the Back to the Future movies and Forrest Gump, but does anyone remember that he directed Romancing the Stone? The story of a frumpy romance novelist who joins forces with an adventurer in the South American jungle is sexy, funny and vastly entertaining, much like the decade that spawned it.

The Game, David Fincher, 1997

The follow-up to Fincher’s beloved Seven is the cryptic tale of a rich financier and his very strange birthday present. It might not be quite as flashy as Fight Club, but it’s definitely just as interesting.

Mona Lisa, Neil Jordan, 1986

Jordan is a fantastic Irish director known for Interview with the Vampire and The Crying Game, but his third film, about a curmudgeonly ex-con who works as a driver for a high-class call girl, should have put him on the map long before a certain famous cross-dressing scene ever did.

Dune, David Lynch, 1984

Yes, I get why Lynch is famous for Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive, and why Dune is considered one of the biggest failures of all time, but I still find it the most entertaining of his films. The freakish, brilliantly intricate world of Frank Herbert’s novel is perfect for Lynch, and I think it’s a sci-fi classic.