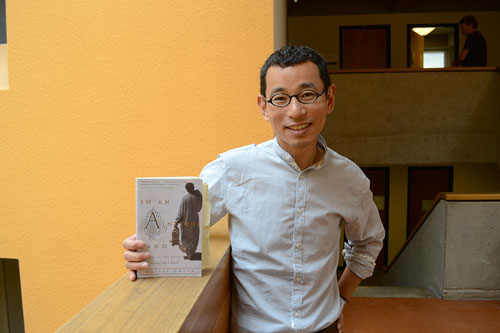

No matter what Thomas Freidman says, globalization is not a new phenomenon. PSU professor Bishupal Limbu’s upcoming talk will touch on this topic and other misperceptions we hold as citizens of the modern world.

Limbu’s lecture is based on the 1994 book In an Antique Land: History in the Guise of a Traveler’s Tale by Amitav Ghosh.

Through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the lecture is sponsored by the Middle East Studies Center, the Bridging Cultures Bookshelf: Muslim Journeys, the Oregon Council of the Social Studies and the Multnomah County Library. It will be held at the county’s Central Library this Friday.

Limbu explained the three layers of the book explored in his lecture: “It is a story about this guy who goes to do field work in Egypt. But before he goes, he discovers a reference—he’s studying at Oxford for a Ph.D. in social anthropology—a very marginal note that refers to an Indian slave, and he’s intrigued. Part of the story is his attempt to recover or to recreate the life of this marginal figure who like himself is from India.

“Another strand of the story is more or less about this world in the 12th century, this medieval world that is depicted as a world of commerce, of trade, and also of this wonderful cosmopolitanism,” Limbu continued. “And this part is about a Jewish trader from Tunisia who lived in the Middle East but then goes on to India.”

In an Antique Land is the rare nonfiction book that reads more like a novel.

“The main part is about Ghosh’s experiences living in two different villages in Egypt—a large part of it is memoir,” Limbu said. “The genre of the book is fascinating because it’s not a dry, anthropological account, it’s…an account that really places the anthropologist [as] the focus of the villagers with whom he interacts.”

Many students have been taught to think of anthropology as a “first world” endeavor. This book, as Limbu said, questions “the figure of the anthropologist being a white person from the first world in a pith helmet who goes to a corner of the third world to do field work.

“It’s to challenge that image, but also notice how because he’s coming from this privileged university…he participates in that sort of power relation of the anthropologist. But…that power relation is very interestingly overturned by the fact that he is himself from a country that is actually the object of anthropology, rather than a place from which anthropologists come,” Limbu continued. “So it’s a very interesting way to subvert traditional notions of what anthropology is.”

The lecture will also subvert our belief in the benefits of living in the modern world and the newness of globalization.

“Ghosh calls it the ladder of development—the notion that modernization is the goal of all societies,” Limbu said. “If you have that kind of idea, both India and Egypt would be really on the bottom rungs of that civilizational ladder.”

That’s one idea that the book tries to both present and critique.

About In an Antique Land: A book discussion with Bishupal Limbu

Friday, May 24, 2:30 p.m.

Multnomah County Central Library

801 SW 10th Ave.

Free and open to the public

“Related to that idea is the focus on cosmopolitanism that Ghosh finds existing in the medieval world that we do not find anymore,” Limbu continued. “We tend to imagine globalization as something that is new and belongs to our age, but one of Ghosh’s projects in this book is to show how globalization has a very long history that stretches at least as far back as the medieval world.

“And it’s also a history that does not only involve, for instance, the West as the lead actor,” Limbu said. “It’s a history that actually involves other parts of the world—the Middle East, India, Asia. The friendships that [formerly] existed across regions of the world, Ghosh finds, are more difficult now.”

Limbu also aims to challenge “the idea that Muslim or Islamic communities are not open, or that their histories are separate from ours, or that the only types of histories worth writing or reading or listening to are the ‘big’ histories.”

Throughout his book, Ghosh highlights oft-overlooked historical characters.

“One of the major themes of this book is the attempt to look at the histories that involve figures on the margins of the stage, about whom we do not know much at all—that is to say, people like you and me,” Limbu said. “When someone writes a history of this moment in time, it’s not going to be about people like you and me, people who will probably be in the audience at the library. So in a sense the book is about us.”