Archeology is more than running from giant boulders and dodging poison arrows, as Indiana Jones films would have you believe.

Old fish bones give new perspective

Archeology is more than running from giant boulders and dodging poison arrows, as Indiana Jones films would have you believe.

It is a discipline whose purpose stretches beyond simply understanding the past; it can inform our decisions for a better future.

By examining animal bones from extinct human settlements, archeologists can see which species historically thrived in certain areas. This data can help conservationists plan accurate habitat restoration and make informed policy decisions based on historical ecology.

It’s a matter of “putting old bones to work in terms of addressing conservation problems,” said Virginia Butler, professor of anthropology at Portland State. “It gives us a baseline of what the world was like before the enormous changes that came with Euro-American arrival.”

One place old bones are getting the detective treatment is the Klamath River Basin. The Klamath flows through Eastern Oregon and Northern California, emptying into the Pacific Ocean. It was an important migration route for anadromous fish—fish that travel back and forth between the ocean and the river to spawn.

Four large dams now divide parts of the Klamath, the first one constructed in 1917, before biological data surveys were common practice. In the last 10 years, the Klamath has experienced a major fish die-off and many of the fish, including Coho salmon, are on the endangered species list.

COURTESY OF VIRGINIA BUTLER

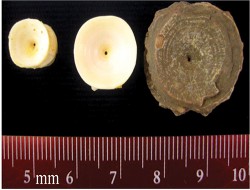

Fish ear bones, or otoliths, modern and ancient, were used to determine which ancient fish spent time between the upper Klamath and the sea

Recently, people have suggested that these dams have had a negative ecological impact, including blocking the passage of anadromous salmon that used to go to the upper basin of the Klamath. The only problem is, they have no record of whether salmon actually lived beyond the dams.

The Department of the Interior is evaluating the possibility of removing the dams, which would happen in 2020, followed by a 50-year review process to determine whether removing the dams served its intended purpose. It could cost billions of dollars.

“We don’t have a basis for what [fish] used to be up there, so using it as a reason to remove four large dams is pretty irresponsible,” Butler said. “Our job was to go though all the archaeology records of fish remains—try to get the ancient DNA from the bones to decipher the species.”

By examining Native American archeological sites along the Klamath and its tributaries, Butler is able to deduce which fish were being caught and used as food as early as 1900, before the dams were built.

Once the species is determined, the next step involves determining if any fish in the upper Klamath Basin spent time at sea and confirming theories that the dams are blocking native fish passage.

To do this, Butler collaborated with Jessica Miller, an assistant professor at Oregon State University and a marine fisheries ecologist. Miller specializes in looking at the chemical makeup of microscopic fish bones called otoliths.

Otoliths are ear bones in fish that essentially help them to keep their balance in water. Made of calcium carbonate, the bones grow in rings like a tree as a fish develops, and store different chemical elements for each water system the fish lives in.

Through examining the chemical properties inside otolith bones, Miller was able to determine if these ancient fish spent time traveling between the upper Klamath and the sea. According to Miller, it’s a great technique for understanding prehistoric communities, and “the best bet for understanding what was happening before we altered the system.”

From 7,000 fish bones, Butler found two anadromous species: Chinook salmon and steelhead trout, making this the first scientific confirmation that the dams along the Klamath River are indeed blocking native fish passage.

“Her work is probably most critical in that regard—demonstrating beyond any reasonable doubt, using the tools of Western science, that salmon were simply present, and that they were utilized for very long periods of human history,” said Douglas Deur, a research professor in the Anthropology Department at PSU.

As an anthropologist, Deur finds Butler’s work important beyond the scope of environmental conservation. Deur works with the Native American tribes in the Klamath Basin. One of his jobs is to record the traditional importance of salmon and historic fishing sites for the Klamath Tribes.

While he does not work with Butler directly, their areas of study in the Klamath overlap. According to Deur, Butler’s discovery of anadromous fish in the upper Klamath Basin “confirms the oral traditions that I have documented, right down to the specific fishing sites that she has documented using bone analysis.”

Since policymakers don’t regard tribal oral history as a reliable tool for environmental decision-making, Butler’s work is helping to validate the stories of the Klamath Tribe elders.

“It is very nice when tribal oral tradition and hard science give us exactly the same result,” Deur said.

Historically, the Klamath River was the third-largest producer of salmon in the West. When the first dam was built, it significantly changed the landscape for the Native American tribes living along the upper basin.

“The Klamath Tribes, whose traditional territories consisted almost entirely of the areas upstream from the dam, were the ones who suffered the most from these changes—losing a staple food and a way of life almost instantaneously,” Deur said.

Butler has spent a lot of her time convincing the world of conservation biology that old bones have a story to tell—a story that can help us understand what our lands looked like and what they provided before major human settlement.

“This use of archaeology for conservation questions—people don’t do it,” Butler said. “Things change gradually and you get used to it. A lot of the losses we are experiencing with these animal and plant populations—whole ecosystems—those are going to have consequences for us and our own health and survival. Archaeology gives you a way to see how dramatic the changes are.”