Why is it so difficult to change certain health behaviors? Things like quitting smoking, beginning an exercise regimen and eating a healthy diet can seem like great feats to many. Are there certain situations or conditions that make these health improvements easier?

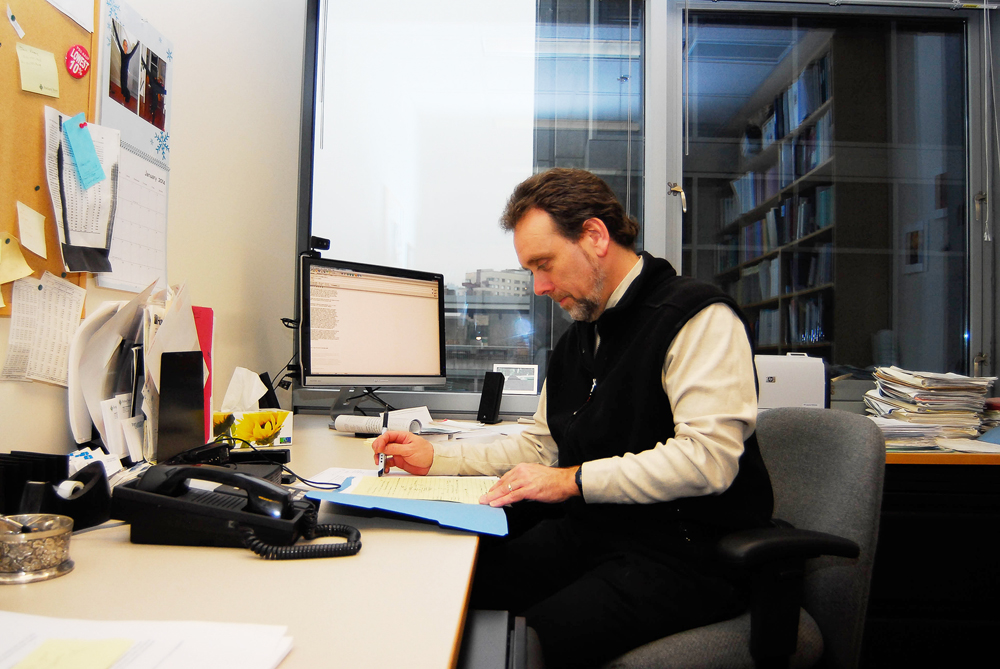

These questions are what piqued the interest of professor Jason Newsom of the School of Community Health at Portland State, leading to the current research that is being conducted by him and his colleagues.

Newsom and his fellow researchers are investigating demographic, socioeconomic and psychological factors, as well as predictors of changes in health behaviors subsequent to a diagnosis of a chronic illness. They have been working with nearly 20 years of pre-existing data to conduct a study analyzing changes in certain health behaviors following diagnoses in mid to late-life individuals.

This data is nationally representative and includes individuals of all demographic categories, aged 50 years and older.

In addition to investigating factors that affect health behavior change, Newsom looks to compare these changes among the chronically ill in order to understand the role of the health care system.

The goal of his investigation is to find new avenues for interventions and ways to advance public health policy surrounding the management of chronic disease.

There are certain limitations of existing studies in this area that Newsom aims to address in his own work.

“Most studies in this area find people after they already have an illness and then ask them about their behaviors prior to the illness,”

Newsom said. His research will include data on people’s behavior prior to being diagnosed, “so [they] have much more accurate information about what [the patient’s] behavior was before their diagnosis.”

A colleague of Newsom’s, Nathalie Huguet, research associate for the Center for Public Health Studies at PSU, added another example of a limitation that will be addressed in their current research.

“Most previous studies only examined one behavior within one condition, and it is difficult to get a general idea of who is making changes based on such a narrow focus,” Huguet said. To surpass this limitation, the current research will focus on several conditions and several behaviors, including alcohol consumption, exercise and quality of diet.

Mark Kaplan, professor of social welfare at the University of California, Los Angeles and another colleague of Newsom’s, added to the limitation Huguet discussed, stating that they will be paying more attention to the importance of comorbidity (the existence of multiple diseases).

“Most elderly people don’t have only one chronic condition,” Kaplan said. “Once they reach a certain age, they are more likely to have two or more chronic conditions,” which he said is a factor that further complicates interventions.

Newsom posed the question in his research, “What conditions or what situations make it more or less likely you will improve your health behaviors?”

Despite a few cases of significant improvements, there is more often no improvement at all.

“Even though some ceased smoking, there were an alarming number who did not change,” Newsom said.

He found that the largest group of those to quit smoking after a diagnosis of chronic illness were individuals diagnosed with a heart condition. However, only 40 percent of that group stopped smoking and the other behaviors included in the study were even less likely to change.

Kaplan added the issue of depression in the chronically ill.

“People who experience chronic disease often experience a related decline in mental health status, and that’s something we need to be concerned about,” Kaplan said. He stressed the importance of the interaction between mind and body, and the fact that people need to understand what mental health factors contribute to healthier physical lives.

Kaplan explained that the unfortunate finding thus far suggests that, overall, the majority of those diagnosed chronically ill do not improve their poor health behaviors. Some individuals’ behaviors even worsen when they learn that they have a serious illness.

Despite the initial expectation that one diagnosed with a potentially life-threatening condition would, as Huguet supposed, “seize the opportunity to lengthen his or her life by changing bad habits into health-promoting ones,” the researchers determined that this is not usually the case.

The research team is looking into what factors come into play in determining whether a chronically ill individual (or anyone, for that matter) will make a positive change in their health regimen. These lifestyle changes are key to promoting quality of life and extending longevity, but the majority of people do not make them.

Newsom and his colleagues are hoping the answers found in their research will have the potential to open up new avenues for successful interventions and ways to more effectively manage chronic illness.