Portland State professor Dr. Evan Thomas has been selected as one of 32 final candidates for two astronaut positions at the Canadian Space Agency. Thomas was an aerospace engineer at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration until 2010, where he developed a $10 million water recovery system currently used on the International Space Station.

The astronaut selection process began with 4,000 candidates who were narrowed down to 32 after background checks, physical exams and cognitive tests. Testing was conducted at the Canadian Forces Base in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and involved obstacle courses, spacecraft maintenance and simulations of landing from space.

Thomas says he is thankful to be considered among such impressive candidates as fighter pilots, special forces members and medical doctors, but being an astronaut is only one small possibility in Thomas’ career.

Currently Thomas is an associate professor in mechanical engineering and public health at the Maseeh College of Engineering and Computer Science at PSU. Thomas’ academic team at PSU develops cellular and satellite sensors in 15 countries to gather data that can help improve global health programs.

In addition, Thomas also founded a public health program in Rwanda that operates in 7,500 villages and supplies clean-burning cookstoves and water filters, and monitors their usage and environmental impact.

Vanguard: Can you describe the work you do now?

Dr. Evan Thomas: What we do in Rwanda is that we focus on water and sanitation and household energy. [Rwandans] cook on open campfires which causes a lot of emissions, a lot of smoke emissions, and diarrhea and pneumonia are the leading causes of illness and death, especially with children in Rwanda.

I’ve been working in Rwanda for about 14 years, through PSU, Oregon Health and Science University, DelAqua, which is a social enterprise I helped start, and the Rwandan government. We distributed water filters and cookstoves [in 2014] to the poorest quarter of households in the entire western province, which is about half a million people with household water filters and cookstoves, and then in 2016 and 2015 we distributed cookstoves to a further 250,000 households, so about a million people. There are about 1.5 million total beneficiaries in Rwanda.

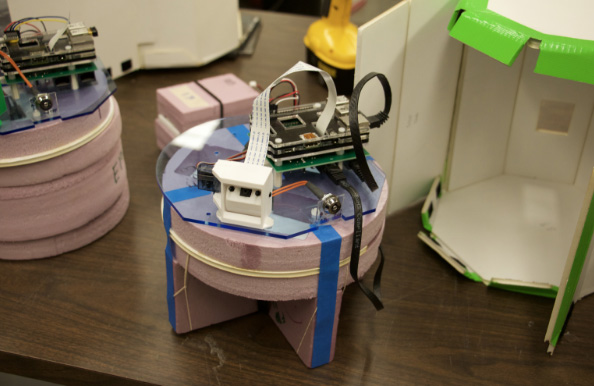

[My team at PSU] develops sensors that are connected to cell phone networks and satellite networks, and remotely monitor the use of these filters, then on the hand pumps and in the latrines. We know when something goes wrong, so we can order to get it serviced remotely. We use drones to assess environmental impact and to monitor biomass in Rwanda and elsewhere.

VG: How does this translate to a career as an astronaut?

EV: The connection for me between global health work in Africa and in Asia and in NASA and the astronaut thing is that I used to work in NASA, where I was an aerospace engineer and did life-support systems.

In terms of human space flight, the technology to keep the astronauts alive and healthy in space are somewhat similar. We recycle the water. We have to monitor air quality. We monitor water quality, and we have to do that monitoring remotely to make sure that the water and air is safe.

And then there’s the question of using earth observation satellites: satellite tools that can remotely monitor surface temperatures [and] can measure where water is, [or] precipitation. [We use drones that can] monitor crop patterns and deforestation. And that data can be made available to decision-makers in these countries to try to address things like famine or drought.

VG: Since some of your work involves monitoring environmental impact, why do you think keeping funding for this kind of work is important?

EV: The hottest places on earth are the places that are least prepared to deal with climate change. Climate change is caused predominantly by the United States, and Europe is rapidly catching up. The people that suffer from [climate change] the most are people in sub-Saharan Africa and Central South America, where there is very little resilience already. We’re seeing changes in crops, we’re seeing changes in water, [and] we’re seeing changes in disease.

There’s a very obvious humanitarian reason to do this work. We live on a planet all together. We have an obligation to each other. Nobody should die of waterborne disease or of pneumonia from cooking with firewood. But there’s also an ethical issue, in that we cause a lot of these problems, industrialized countries cause a lot of these problems, so we have an obligation. It’s our problem.

VG: If you are not selected by the Canadian Space Agency, will you continue at PSU, or is this a turning point for you?

EV: It’s a time to bring together these two fields. So this piece about using earth observation and space exploration as a tool to try to address poverty here in the world is something that has been growing for our research team, so we’d be doing more of that.

I’m very unlikely to get this opportunity. Competition is incredibly fierce. But just being part of this competition has really invigorated my interest in this area.