Rarely do you get a chance to see what your education is tangibly doing for you, or for anyone else for that matter. You sit in your class and repeat French verb conjugations or mathematical algorithms, and while it makes you sound exceedingly clever, that’s probably the extent of its effect your life. Unless, of course, you’re moving to France this summer to date a mathematician.

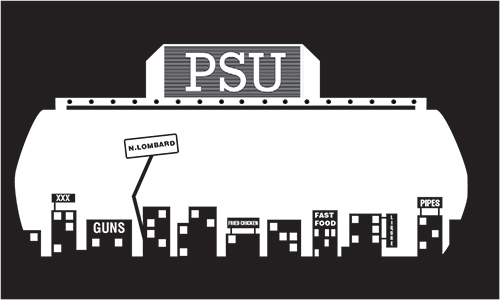

PSU students have plans for Lombard Street

Rarely do you get a chance to see what your education is tangibly doing for you, or for anyone else for that matter. You sit in your class and repeat French verb conjugations or mathematical algorithms, and while it makes you sound exceedingly clever, that’s probably the extent of its effect your life. Unless, of course, you’re moving to France this summer to date a

mathematician.

On some level, we know that much of what we’re ingesting will occupy our brains for a time but likely never be accessed again. We’re OK with that, though, because after all the degree’s the thing—and if all roads lead to that, we’ve just got to keep walking, right?

When you get to experience the effects of what you’re learning firsthand, it’s a gift. When you realize you don’t have to wait to be done with school to start impacting the world for the better, then education has done its job. Take, for example, a group of graduate students in Portland State’s Master of Urban and Regional Planning program.

They recently spent two months reaching out to residents living near North Lombard Street for the Lombard Re-Imagined project. The project’s goal is to “develop a vision for Lombard, focusing on how it can become a more walkable place with a unique identity that better serves the needs and wants of its neighbors,” according to the project website.

The area they’re focusing on is a “two-mile stretch of Lombard between [Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and North Chautauqua Boulevard],” where they surveyed almost 800 people about what changes they’d like to see. Seventy-two percent of respondents said street improvements like trees and more lights were needed, 65 percent said more businesses would liven it up and 43 percent wanted more bike facilities.

The students took this information and went to work.

They came up with a number of solutions, from establishing a weekend farmers market in an empty parking lot to filling another lot with trees and creating an outdoor seating area. There were suggestions for bike corrals and welcome signs to give a neighborhood feel to the area. They included plans such as a bike track, curb extensions and flashing lights for pedestrian crossings. Carefully detailed maps outlined each of their plans.

Great, right? Perhaps.

Looking at the ideas and their proposed costs, I have to admit that initially I was dubious. I wondered if this was just another case of neighborhood gentrification, which always sounds oh-so-fabulous in theory but almost always ends up hurting residents of color. North Portland is a historical example of this very thing and I wondered if PSU had just spit out a bunch of new students embodying the same old philosophies. Then I read the group’s blog.

Taking all their plans into consideration, the students asked the million-dollar question: “Whose vision will this plan represent?” They readily acknowledged that their online survey represented a narrow demographic: largely, white females.

They observed that: “In a city where people of color have been alternately redlined into neighborhoods only to be pushed out of them by gentrification decades later, North Portland is still a place where diversity, color and culture can call home. Any ‘community vision’ must reflect this defining aspect of the neighborhood.”

Instead of simply accepting these obvious limits to their research, they approached the issue from a different angle, contacting church leaders and public agencies in the area for advice on how to successfully reach underrepresented populations.

Thanks to these connections, students arranged “coffee talks” and meetings with a diverse array of people, also going door to door with interpreters to engage Spanish-speaking residents and business owners. The students reported that some of the most valuable information they received came as a result of this method of engaging residents.

It’s impossible to create a fault-proof plan when it comes to housing and neighborhoods. What makes me hopeful is that the students displayed an understanding of the complexities of their venture and approached it from a perspective that included, and was concerned with, all members of the community—not just those who were most visible.

I feel optimistic when I see that our education has the potential to change things, to undermine the status quo, to stop cycles of injustice and marginalization one plan at a time. If we let it, of course—if we realize that it’s not about a degree on a piece of paper but about the degree to which we use it.

Great column… thanks for writing about the work of our students, and about the necessity pursuing engagement broadly. One small comment: this was a 6-month, not 2-month project. The MURP Workshop takes place in the winter and spring terms every year, and serves as the “capstone” for the Master of Urban and Regional Planning degree program. These students have been doing great work for a long time. To see more regarding projects over the last 10 years, check out:

http://www.pdx.edu/usp/master-of-urban-and-regional-planning-workshop-projects

Thanks!