A new study published by scientists at Portland State suggests—contrary to the findings of several previous studies—methane emissions into the Earth’s atmosphere are continuing to increase into the 21st century.

Based on the study’s findings, one major source of methane comes from leaks caused by operations in the fossil fuel and natural gas industries, according to Andrew Rice, associate professor of physics at PSU and one of the study’s authors. Improvements in the efficiency of efforts to capture this gas could provide both a boon to the environment and corporations that could then sell it for energy production, he added.

Much of the study’s data came from analysis of isotopes in an archive of air canisters originally collected at Cape Meares on the Oregon coast and then stored at the university, Rice said, adding that some of these canisters date back as late as the 1980s.

This variety of analysis only became commonplace at the start of the 21st century, he explained; as such, opportunities to perform isotopic analysis on air from before then are hard to come by.

“We went back and analyzed more than 300 samples, looking at carbon isotopes, looking at hydrogen isotopes and then we had this data set which was quite unique at the time,” Rice said.

Different sources of methane and other gases have different ratios of isotopes, meaning that examining these ratios can give researchers an idea of where those gases came from, Rice explained.

“We could have stopped there and just kind of posted the data,” Rice said. “Instead we decided to work with my colleague Chris Butenhoff. He’s an atmospheric modeler. What atmospheric models allow you to do is try to make the connection between the sources—what is being emitted on the surface and the atmosphere, what you measure in the atmosphere.”

Christopher Butenhoff, assistant professor of physics at PSU, was another of the study’s authors. He and some of his graduate students were responsible for using inverse modeling to correlate specific isotopes of methane in the atmosphere with their sources over time.

Throughout most of the 20th century, the growth rate of methane in the atmosphere was consistently high, according to Butenhoff.

“Starting maybe in the 1990s, the amount of methane in the atmosphere was actually starting to flatten out a bit,” he said.

Butenhoff explained this trend changed in 2007, however, and that one of the study’s main goals was to explain the resurgence of atmospheric methane growth.

“From a policy perspective this is really important, because if we are going to control and mitigate climate and greenhouse gases, we have to know what’s causing these changes in the atmosphere,” Butenhoff said.

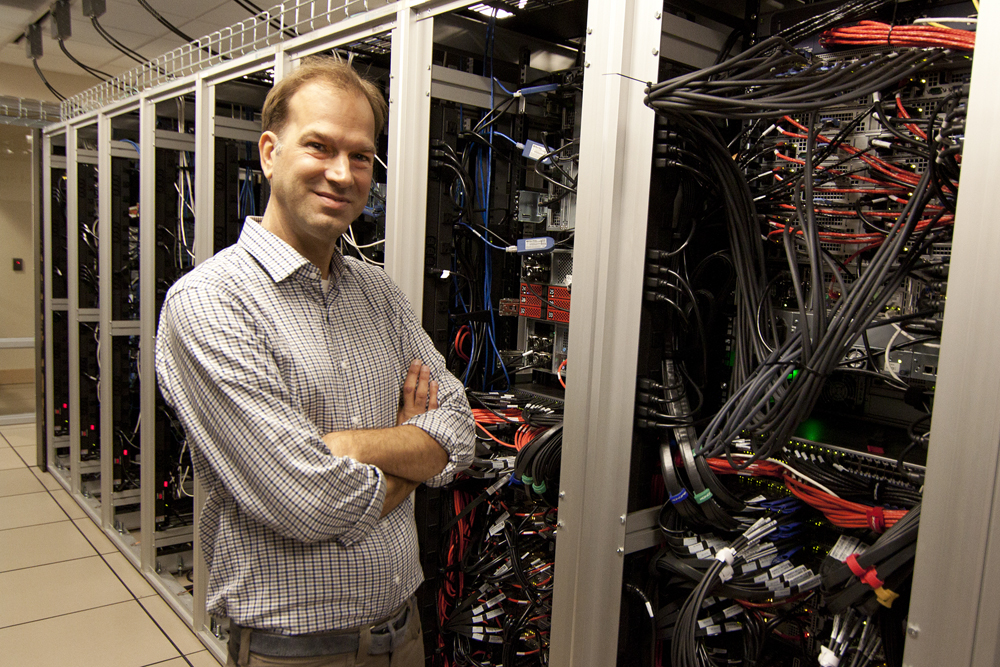

Interview with the professors behind the study. Miles Sanguinetti/PSU Vanguard

Anthropogenic sources of methane—those caused by human industry—including release from oil fields, fracking, landfills and livestock are all on the rise, according to Butenhoff. Prior to 2007, these were offset by a decrease in non-anthropogenic methane release from places like wetlands. Between 2007 and 2014, however, wetland emissions have increased, resulting in an overall increase in methane in the atmosphere.

The methane released by wetlands has been linked with climate change and, as a consequence, cannot be stopped as directly as if it were caused by industry in and of itself, Butenhoff added.

“If that’s kind of how our climate’s heading, then it kind of limits our options to how we can mitigate or reduce methane emissions,” Butenhoff said.

An earlier study by Lassey Research out of New Zealand titled “A 21st-century shift from fossil-fuel to biogenic methane emissions indicated by 13CH4,” published in Science Magazine in April 2016, produced findings in conflict with the conclusions of the PSU study.

Heinrich Schaefer, the study’s corresponding author, stated in an email that though the studies’ results were in disagreement, neither could disprove the other.

“The methane (CH4) budget is so complex that the same isotope trend can be explained by different emission scenarios,” Schaefer stated. “Ultimately, it comes down to which of the associated changes in sources other than fossil fuels you consider more plausible.”

Varying degrees of increase and decline of fossil fuel use, biomass burning and wetland methane emission form a number of possible explanations, he added.

“[Their] preferred scenario also conflicts with observations of decreasing ethane levels (co-emitted with CH4 from fossil fuel sources), which, according to the study itself, is consistent with decreasing or stable but not increasing fossil fuel methane,” Schaefer stated.