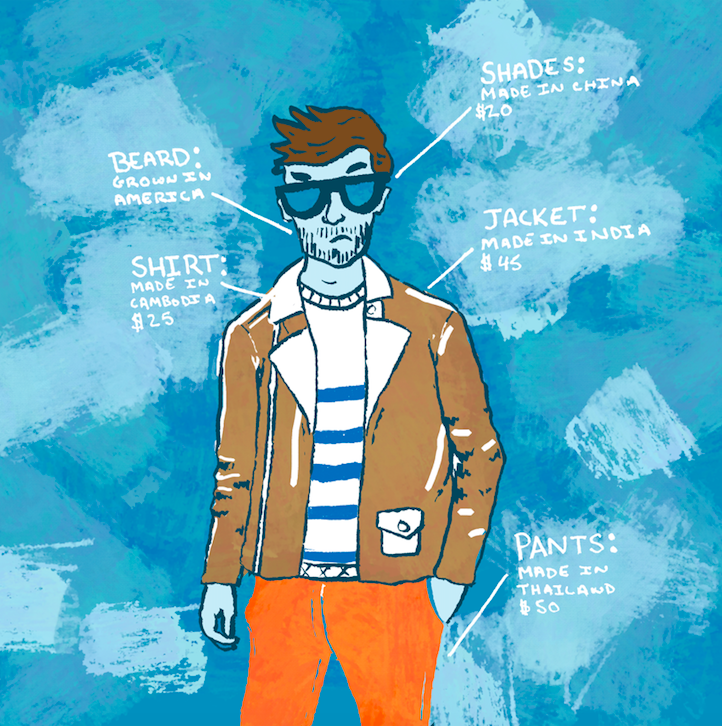

Recently, while out searching for a cozy and fashionable coat to get me through the winter, I decided I would take on the challenge of looking for a coat that came from ethical means of production and wasn’t too expensive.

After starting my research, I was disheartened to discover the scale of labor exploitation within the fashion industry.

The problem starts closer to home than you might think.

“Today large brand companies hire manufacturers who in turn hire subcontractors to produce their products,” wrote Jennifer Back, author of the academic essay “Sustainable and Ethical Practices for the Fast Fashion Industry” for Occidental College. “By hiring subcontractors, companies are able to disassociate themselves from any human rights or environmental violations that often occur during production.”

Exploitation often manifests in the process of promoting fast fashion, an industry term for producing inexpensive, trendy clothing featured in bi-annual runway shows—the hot clothes that everyone wants as soon as the trend becomes… trendy. However, many popular retailers violate ethical practices indirectly.

Especially disappointing was the discovery that almost all the stores I had originally intended to buy from are involved in some pretty questionable, if not revolting, behavior.

I used a combination of ethical consumption apps on my phone and independent research to decide whether H&M, the first store on my list, was ethical enough. Though H&M seems to have a good start at ethical production, it still has a long way to go. Environmentally, the company recycles and is part of the Better Cotton Program. Yet it still uses mostly non-environmentally friendly materials. H&M has pledged to become completely environmentally friendly by 2040, but this is simply a goal and quite far in the future.

Although the 2017 Ethical Fashion Report, a Christian aid and development organization, gave H&M a grade of B+, the company seems to have gone backward over the past year in regard to traceability and transparency of its suppliers.

After more digging, I discovered that the company has an unsavory history. Though H&M may have since improved its working conditions, Business Insider reporter Nita Bhalla reported in a May 2016 article that H&M forced its employees to work overtime, fired workers after they became pregnant and used fixed-term contracts.

The next store I usually shop for clothes is Forever 21. This company received a D- grade from the 2017 Ethical Fashion Report because it currently does not pay living wages and has made practically no progress toward ensuring one. It likely does not publicly list its suppliers (which means it could be using factories infamous for unethical practices) and lacks any worker empowerment initiatives. The company also does not publish sufficient or relevant information about its environmental practices aligning with Ethical Fashion Report standards.

Surprisingly, I discovered that not all of Forever 21’s labor is outsourced outside the U.S., yet even domestically, the company has been caught engaging in unethical practices. According to a 2016 LA Times article from Natalie Kitroeff, workers in a downtown Los Angeles factory were paid an average $7 per hour, $3 less than minimum wage. In some cases workers were paid as little as $4 per hour.

Another store I was a fan of is Zara, a fast-fashion company out of Spain and now popular around the globe. Similar to H&M, Zara has set many environmental goals for itself to achieve in the future: It has aimed to reduce its current carbon emissions by 20 percent and eliminate hazardous chemicals by the year 2020.

When it comes to labor, Zara is fairly transparent in its practices and has good worker empowerment initiatives in some of its supply chain factories, yet this seems to be outweighed by little to no progress toward paying living wages across its supply chain.

Though it’s encouraging to see fast-fashion companies making strides toward positive ethical changes by setting deadlines for themselves, it’s still not enough. Consumers need to push for change now, not in 40 years.

Without immediate action, we risk not only the planet but also the livelihood and safety of fast fashion supply chain workers. Unethical labor practices caused disasters like the 2013 Rana Plaza factory disaster, in which an eight-story factory in Bangladesh collapsed, killing over 1,000 workers. This demonstrates what happens when cheap prices cause manufacturers to cut corners, and as the demand for low prices keeps rising, who knows how close we are to history repeating itself.

Grueling labor practices employed in work environments associated with the term ‘sweatshop’ might seem like an accepted negative, but this opinion isn’t exactly universal.

Some business owners and economists believe these working conditions benefit fledgling economies by they creating jobs that pave the way for higher standards of living.

“Low wages, unsafe conditions, and factory disasters are all excused because of the needed jobs they create for people with no alternatives,” said the narrator of the film The True Cost, a documentary about what goes on behind the scenes of fashion production. “This story has become the narrative, used to explain how the fashion industry operates all over the world.”

So why aren’t people taking a stand against the mistreatment of textile workers? Beside fast fashion’s convenience and cost efficiency, perhaps a large reason no one speaks out against these companies is no one knows it’s happening.

Interrupt the fast fashion food chain

The good news: Consumers can help to draw attention to the issue. To paraphrase Portland State marketing Professor Brian Bolton, author of Sustainable Financial Investments, the power of protest and word of mouth is evident in cases like Nike, where the company’s abusive labor conditions soiled its name and effectively forced it to become one of the first companies to have a board-level sustainability committee.

However, if we want to make real strides toward changing the habits of large fashion corporations, we need to start by changing our habits as consumers. “We—directly or indirectly—endorse company values by giving them money (or labor or other resources). The best way to change this is by not giving the companies our money,” Bolton said.

Although it feels inconvenient, if a significant amount of us made the conscious effort to make changes to our shopping habits, even starting with small, seemingly insignificant changes, we could make huge strides.

Americans buy five times more clothing now than in 1980, yet according to The Atlantic, Americans send 10.5 million tons of clothing to landfills every year.

A large part of the problem lies within the cultural pressure to always wear something new. We are attracted to fast fashion because we’re part of an extremely value-oriented population, and fast fashion allows us to keep buying more and get good bargains. Yet we fail to realize we would save money by buying fewer clothes that last longer and cost more, rather than inexpensive clothes that often don’t last longer than a season.

With the innovations of the internet, we have better access to resources which make it easier to shop ethically. For example, apps and websites like Good on You, Avoid and Good Guide allow shoppers to discover more about clothing companies’ production practices and make informed buying decisions.

Ethical shopping is complicated. “It’s difficult to always act on our values, and nobody should ever be expected to be perfect,” Bolton said. “But the more conscious we are of what we’re doing and which companies we support, the bigger impact we can have on those companies we disagree with and on society.”

December has amassed the highest average retail sales by month for more than 25 years, and historically accounts for at least 20 percent of a year’s total retail sales. This holiday season, as in right now, is a prime opportunity to make ethical buying decisions at a time when clothing companies are surely paying attention.