Rockstar Games disappoints once again.

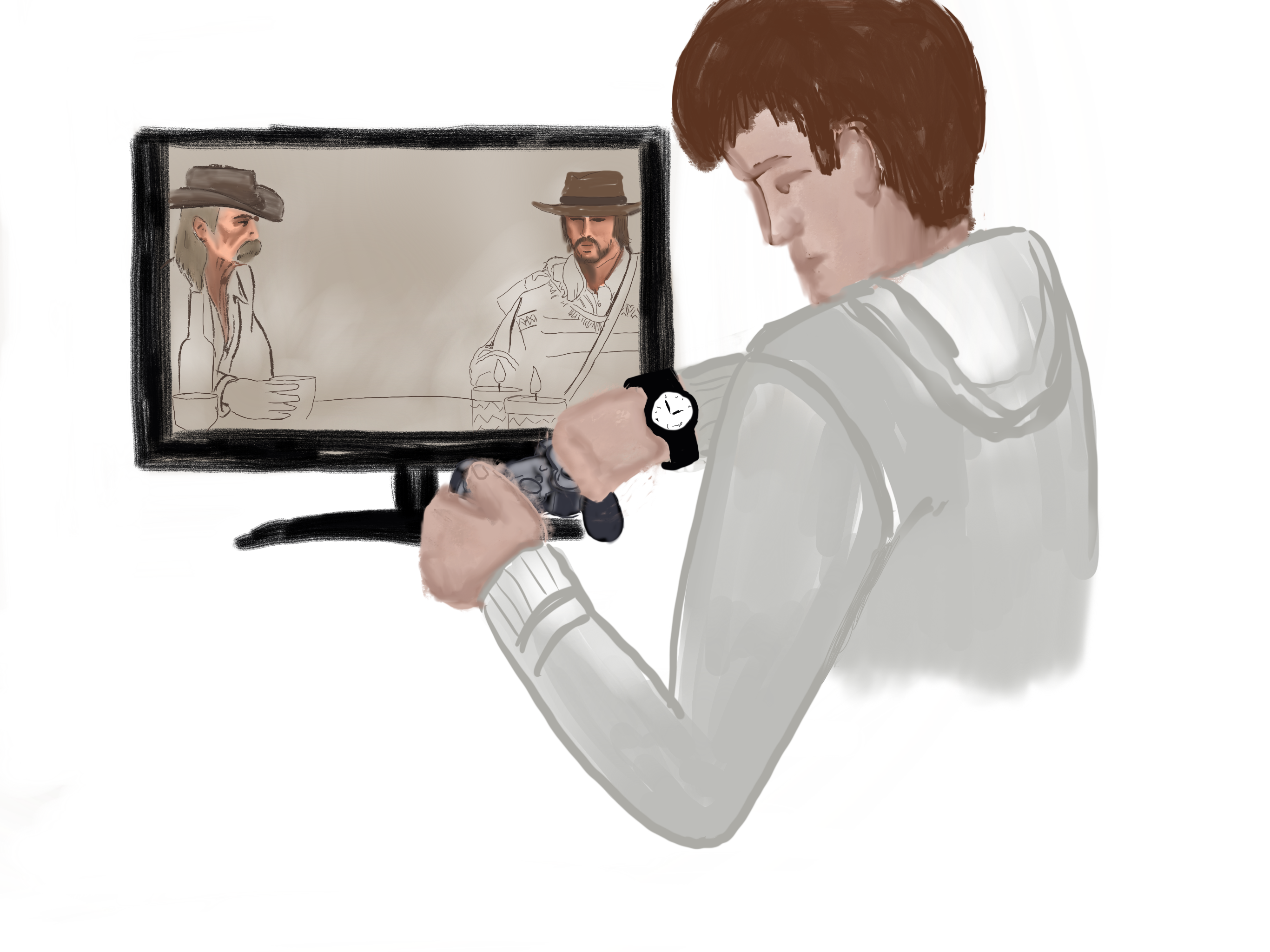

While sales for Red Dead Redemption II hit the $725 million mark within three days of its release, the sequel’s unnecessary hyperrealism—which has become a trend in games—makes it a massive mess of mediocrity.

News of the game first leaked about a year and a half ago, after it had reportedly been in development for seven years by a team of 3,000 people, but all that hard work and overtime produced a game that is too realistic.

For example, the game’s opening sequence took me several hours to get through, as I walked in the snow, hunted deer and fixed a wheel, all in excessive detail. It should have taken me an hour.

Don’t get me wrong; realism has its place, as in the tense gameplay of DayZ. In Red Dead II, though, the concept of escapist fiction hasn’t just taken a back seat—it has been tossed in the trunk. There is no suspension of disbelief. At one point in the game, I could not see a thing at night with the brightness at the suggested setting, and the lantern hardly worked.

Red Dead II was obviously an expensive game to make. A beautifully detailed American frontier streams by non-stop throughout the courses. The gunplay shines as the most realistic aspect of the game, and you can feel the weight and draw of each gun in real time. But that’s about it.

Tremendous graphics with poor gameplay raise the question: Where did the rest of the game’s production budget go? The answer: to the marketing department’s intense advertising push and high-end art design. The scary part is that this trend isn’t new; the mini-movies between game levels have existed for years in their own separate space.

Telltale Games popularized this approach with its Walking Dead series and The Wolf Among Us, but it proved to be merely a quick fix, as the studio announced in September it would be shutting down. After the well-liked Walking Dead series, the quality of Telltale games dipped, especially with Batman: The Telltale Series, in which an inaccurate interpretation of the character exposes Batman’s secret identity early in the first episode.

The main issue with games such as Red Dead II is the novelty wears off quickly. If I want to watch a movie, I’ll watch a movie, but if I’m going to play a video game, I want to really play. When a company phones in both its movie sequences and its gameplay, it feels disingenuous, which is sad considering the market can essentially be used to fool people into a concept. This happened with No Man’s Sky, which upon release was forced to issue a massive recall due to a similar misrepresentation.

Red Dead Redemption II depends on reality in an escapist medium, but do I want to do my taxes in a game? Do I want to apply for financial aid in a game? No. Who would? This trend doesn’t appear to be slowing down but rather spilling into other video games.

I totally agree with your stance on the game being too realistic. I thought it was a joke when I watched my friends playing and realized that their travel sequences were happening in real time. I almost couldn’t believe it. I don’t see the point of essentially forcing your player to put on cinematic mode for nearly 30 minutes in order to “realistically” get from point A to point B. That’s ridiculous! It’s a GAME. Which means the laws of physics can be stretched a little bit for the convenience of the player. Overall, I think the graphics are beautifully rendered and the character development is commendable. Did I except a little more? Yes. Is it still fun to play? Sure. Do I recommend for those who want a true gaming experience. Maybe not.

Thanks for your article! Great read!