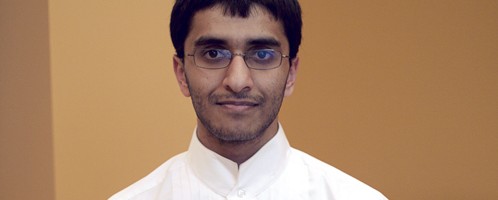

Kanaan Kanaan, a Portland State Middle East Studies student adviser, was named after the Canaanites, who were among the earliest inhabitants of the ancient Middle East and, therefore, among the earliest influences on the Arabic language. In the wake of 9/11, Kanaan has used Arabic to communicate positive elements of Islamic culture.

Sacred language

Kanaan Kanaan, a Portland State Middle East Studies student adviser, was named after the Canaanites, who were among the earliest inhabitants of the ancient Middle East and, therefore, among the earliest influences on the Arabic language. In the wake of 9/11, Kanaan has used Arabic to communicate positive elements of Islamic culture.

He will hold an Arabic calligraphy workshop at the Millar Library Thursday, which will begin with a quick presentation on the importance of Arabic in Islamic culture.

Arabic speakers make up a minority of Muslims, according to Kanaan. There are only 350 million Arabs compared to 1.5 billion Muslims.

“But the Arabic language is really crucial to Islam because the Qur’an is written in Arabic, so it is considered a sacred language for all Muslims,” Kanaan said. “So most Muslims, even though Arabic is not their language, read the Qur’an in Arabic.”

Kanaan will introduce students to basic but very fluid and geometrical forms of Arabic calligraphy, including Kufic, the oldest form.

“It is not an easy form for Westerners to learn, not even for native speakers,” Kanaan said. “But I can show [American students] different forms of letters and different scripts and then start with graph paper, where people just learn to write their names.”

Kanaan’s workshop is actually part of an ongoing exhibition, The Gift of the Word, which has ancient Arabic scrolls on display in the Millar Library.

“When you look at some ancient texts, all you have to do is meditate, stay still and be silent in respect for that work. That work is a form of a prayer,” Kanaan said. “The person who hand-wrote it hundreds of years ago put so much blood and sweat into it that they really shaped each letter and stroke with their heart, their mind and their spirit in it.”

Born in Amman, Jordan, Kanaan’s art career began in the 1980s when he studied at the College of Fine Arts at Iraq’s Baghdad University. He immigrated to the United States in 1994 to study and graduated from PSU in 1999 with a bachelor’s degree in fine arts and graphic design. He went on to receive his Master of Fine Arts degree in painting and mixed media at Warnborough University in Ireland.

Kanaan learned English as a second language, worked as a professional artist and taught graphic design courses at PSU for eight years. He initially drew abstract artwork, but after 9/11 he turned to more traditional Islamic art.

“I use my artwork as a tool to open the eye on Islamic art, to see the other part of Islam besides the bad rep that Muslims have through the media,” Kanaan said. “And I use it as a tool for dialogue.”

Kanaan has involved himself in similar workshops since his teens. Sept. 11, however, sparked curiosity about Islamic culture in American society, so Kanaan has given lectures at churches, schools and universities, teaching people of all ages from kindergartners to senior citizens.

“It really goes back to this cultural interaction other than just learning how to be a calligrapher,” Kanaan said. “You can spend years and years trying to master one of the forms, and you may not. But there is a pleasure in doing that. And in the process of doing these workshops, I learn more about myself and my culture.”

Arabic spread across the Middle East thanks to Islam’s rise in the sixth century. Arabs transported the language from the Arabian peninsula, largely displacing other Semitic languages in the area, until only two survived: Arabic and Hebrew.

Kanaan seeks to teach non-Muslims about how Islamic culture and civilization shaped the modern world.

“There was instrument, called the thisterlav, invented by a Syrian Arab, and it’s one of Vasco da Gama’s legacies that he explored the seas using that instrument,” Kanaan said. “So it’s ironic that you have this rich influence and rich civilization about which very simple things are not mentioned.”

He often receives emails from people complimenting him on his artwork.

“It is satisfactory because I know I reached someone in a very peaceful manner. No competition, just colors. They didn’t read, they didn’t understand what it is, but they feel connected to it,” he explained. “When I tell them what it means, their jaw drops—that’s what I love about it.”

Writing bears special significance in Islamic culture as a transmission of ideas through the ages. Kanaan worked on an exhibition he called Image vs. Word, in which he compared Christian iconic images to Arabic words.

“Combining the power of the spirituality of Christianity and the power of the word in Islam, you end up in the same place if you really and truly believe in humanity and spirituality,” Kannan said.

Comparing Arabic calligraphy to Japanese and Chinese calligraphy, Kanaan notes that the written languages flow in a similar manner, but what fascinates him is the use of ink on rice paper, which will be used in the workshop.

Kanaan performed a workshop at the juvenile facility in Woodburn and marveled at the change in the behavior of the juveniles as they painted a mural. They gained respect for each other and the maturity they previously lacked. Their attitudes seemed to change wholly for the better.

“Our job as a society is to reconnect and use different tools to do that, and I use art to do that kind of change,” Kanaan said. “Calligraphy, because it’s unique and culturally specific, and because right now there’s a hot climate for Arabic and Islam—that’s why I’m using Arabic forms and letters in my art.”

Kanaan Kanaan’s Arabic calligraphy workshop

Thursday, May 10

3 p.m.

Millar Library

Free and open to the public.

Do you give classes?