Over the past few years, drones have begun to shape how archaeologists survey and document sites.

Drones are both cheaper and faster than older aerial surveillance methods such as helicopters. They are especially useful in places like Peru and the Middle East because many archaeological sites reside in large, open areas that take a long time to document and are difficult to protect against looting.

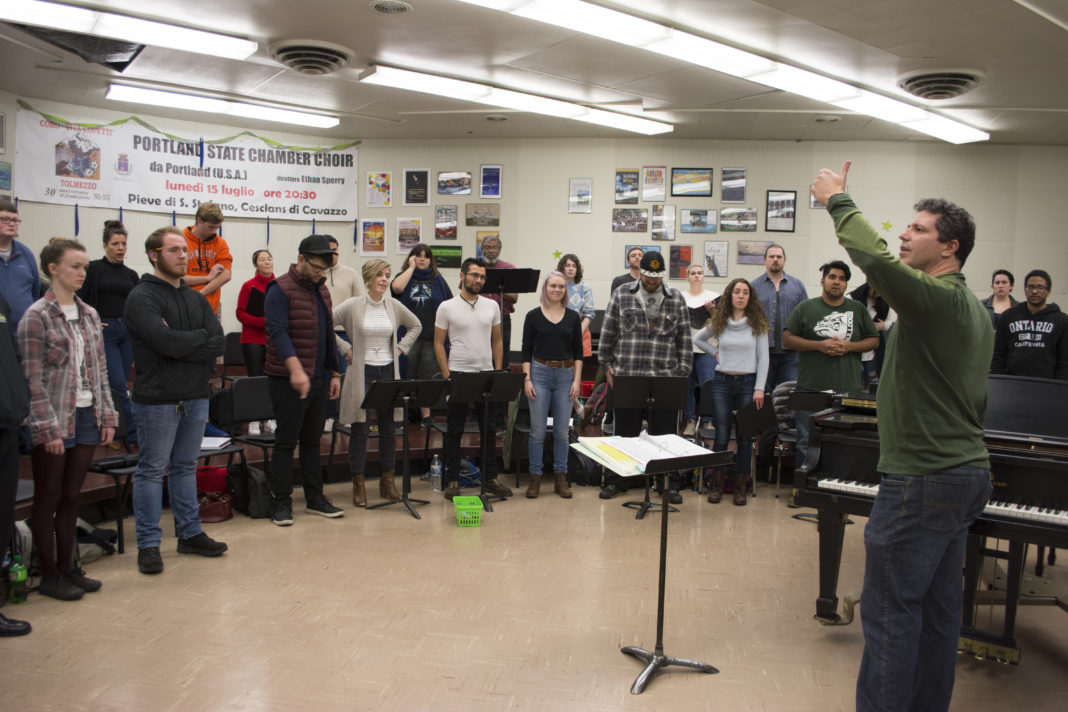

“I expect they will become part of the archaeologist’s ‘tool kit’ in the next 10 years,” said Dr. Virginia Butler, a professor of anthropology at Portland State whose life’s work focuses on archaeology.

Looting protection

A prominent example of this new method of drone use was cited by the New York Times. In Chepén, Peru, at a remote archaeological dig site a drone helps to protect against looters.

Drones outfitted with cameras increase the likelihood of catching criminals in the act of looting because they monitor expansive areas of land.

“Looting often [takes] place on large open sites in arid areas,” Butler said.

Butler’s professional focus has been on zooarchaeology, the study of animal remains at archaeological sites. Based on her experience, she agrees that the use of drones could be a beneficial method for aerial surveys of the open, arid regions vulnerable to potential looting—especially if these sites have clear structural visibility.

According to the Smithsonian, looters have begun to sell artifacts in the Middle East to maintain their gun supply for the Syrian war, making drone surveillance in these areas a necessary part of the archaeologists’ budget.

For humans, archaeological sites situated in areas like Peru are the most difficult to protect and maintain; for drones it’s the opposite.

3D imaging

Justin Junge, a PSU graduate student of anthropology, stated that the quick mapping capabilities of a drone would have helped a project he worked on in Greenland in 2012.

Using a helicopter, “the goal was to get a bird’s eye view of features and relationships between sites” but the helicopter wasn’t stable enough to provide the quality of information that was necessary to complete the project. Drones are “cheaper with their initial cost, training, and fuel/power to use,” Junge said. Drones can also fly lower as compared to larger aerial vehicles, so the quality of information captured is better.

Peru has around 100,000 archaeological sites, but only 2,500 are currently mapped. Drones can help in covering these areas before they vanish.

Chicago University’s archaeology team has also used drone surveillance at a dig site in the Black East Desert in Jordan. The desert is characterized by seemingly common sand mounds, which land surveyors would expect to observe in such regions. But 3D photographs from drones paint a different picture: many unexplained collapsed structures that lay beneath the mounds date back 8,000 years. The team conducting the study, The Oriental Institute, employed several types of aerial survey vehicles and found that drones delivered the clearest photographs.

Researchers are using this new type of surveillance to shine a light on the the complicated and once mysterious journey that led to current civilization in the Black East Desert.

At a cemetery in Fifa that dates between 3600 and 3200 B.C., researchers captured images of a 64,000-acre area with “1 to 2 centimeters per pixel,” a great victory for those interested in preserving this vast historic site.

With the use of a drone, Cerro Chepén, a site in Peru that dates back to 850 A.D., was photographed in 10 minutes and mapped in 24 hours. Drone images capture important information that 2D aerial photographs cannot—including artifact placement, variations in terrain and elevation.

Drones use a combination of Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) and radar technology, or harmless laser scanners and radars, that leave archaeological sites in tact. Digging things up requires destruction and always results in artifact casualties, whereas using a drone is potentially harmless.

However, there is still room for improvement. According to the New York Times, “drone batteries can last for as little as six minutes” and the dust in the arid climates can destroy the equipment.