Eight years after the lockout that stole the 2004–05 season, NHL players offered the league’s owners an extension of the collective bargaining agreement as it came up for renewal this summer. Despite suffering a 24 percent salary rollback (after losing the battle on the salary cap issue in 2005), members of the NHL Players’ Association were more than happy to continue playing under the same terms that had been hammered out after that lost season.

The lockout, part 2: missed opportunities

Eight years after the lockout that stole the 2004–05 season, NHL players offered the league’s owners an extension of the collective bargaining agreement as it came up for renewal this summer. Despite suffering a 24 percent salary rollback (after losing the battle on the salary cap issue in 2005), members of the NHL Players’ Association were more than happy to continue playing under the same terms that had been hammered out after that lost season.

Failing once again to learn from its troubled history, the NHL repeated its mistakes from 1994–95 and 2004–05 and used the opportunity to lock out the players. Somehow expecting men who wield sticks and strap razors to their feet for a living to capitulate to their every demand—as the players had been duped into doing for three decades under NHLPA Director Alan Eagleson—Gary Bettman and the owners interrupted a third season in 18 years expecting different results.

The official terms of the new collective bargaining agreement indicate, as expected, that the owners gained greater control of revenue. They won their biggest battle of the CBA war when they succeeded in decreasing the players’ share of hockey-related revenue from 57 percent to 50 percent and capped the length of player contracts at seven years (eight for teams re-signing their own players). It’s the sort of deal that more clearly defines how such terms tend to be worked out in the NHL.

But the truth beyond the agreement is that the NHL fought for and won peripheral gains for its owners while failing to address the core issues that will continue to plague the league going forward. The new CBA also did nothing to ease the enmity that has persisted between the NHL and NHLPA since Eagleson was deposed in 1992, further alienating the fans, broadcasters and sponsors which any professional sports league

depends on for survival.

Ballooning from 21 to 30 teams over the past 20 years, the league chased expansion revenue anywhere they found it, without ever considering the long-term ramifications. By dropping franchises into cities without a viable hockey culture, the NHL vainly expected a fan base to rise out of the desert. According to a special report by Forbes, 2004 Stanley Cup winner Tampa Bay loses $13.1 million annually, 2006 champion Carolina operates at a $9.4 million deficit and 2007 winner Anaheim bleeds $10.8 million each season. They are three among 13 teams in the NHL that lose money as a matter of annual ritual.

While the overall operating income of the league doubled to $250 million in 2012, a full one-third of that total was brought in by the Toronto Maple Leafs. The Original Six teams—Toronto, the Montreal Canadiens, Chicago Blackhawks, Detroit Red Wings, Boston Bruins and New York Rangers—alone create $263 million in income. With nearly half the league’s teams losing money, none of the concessions won in the new CBA could hope to rectify the income disparity.

The league did indeed increase its revenue-sharing program, but that program does nothing to assist teams like Anaheim or the New York Islanders, who play in large metropolitan areas but suffer financially as second fiddle to the Los Angeles Kings and New York Rangers. For the eight teams with operating losses of at least $10 million yearly, not even an increase in revenue share will automatically turn red ink into black.

Established owners who were happy to take expansion fees have shown no desire to work together in order to plug the cash drain of those fledgling franchises. Because the previous lockout drastically reduced their television revenue, the NHL’s dependence on gate receipts only managed to magnify the gap between rich and poor teams. The Tampa Bay Lightning, for example, averaged more paying customers per home game than the New York Rangers last season, yet the Lightning lost millions while the Rangers had an operating income of $74 million. Why? Because New York can charge almost double what Tampa Bay can to fill the same number of seats. The Rangers pull in around $20 million more per season from attendance alone.

The salary cap implemented after the 2004–05 lockout was supposed to make small-market teams more competitive on and off the ice. What happened was that the cornerstone teams of the league pocketed more revenue instead of spending it on salaries. Carolina or Anaheim might win the Stanley Cup, but that was no guarantee that they would be profitable.

Until NHL owners learn that hockey players are vital partners rather than adversaries, they will continue to view lockouts as an effective labor-management tool rather than a detriment to the long-term health of the league. And until the flagship franchises recognize their struggling brethren as equal partners, the league will never reach its full potential. Yet the fans always come back, gearing up for whatever allotment of the product they’re left with after the latest labor dispute.

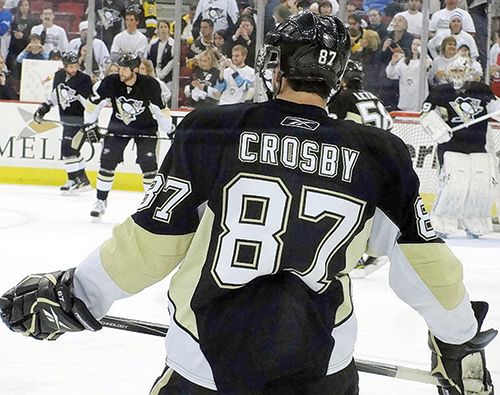

The reasoning behind this level of committed masochism is simple. For all its financial flaws and ineptitude in contractual negotiations, media and fan relations, the NHL still offers the highest level of professional hockey to be found anywhere in the world. The sport offers spectators a blend of physicality, speed, teamwork and individual skill that can easily translate to fans of other sports—a sort of athletic meritocracy wherein physical stature is neither an ingrained advantage nor an automatic impediment when determining a player’s rise to the top.

The latest lockout may prove to be just another holding maneuver in a long line of botched dialogue between players and owners, but the quality of the product in the rink will continue to be as high as ever. With only 48 games available to determine playoff spots instead of the standard 82, each regular-season contest will be played with greater intensity and focus. All the headaches that the NHL forces its fans to endure can’t change the fact that this could be the season you see your favorite team come out of the playoffs raising the Stanley Cup, the single greatest trophy in sports. That’s one concession that will never go to the owners.