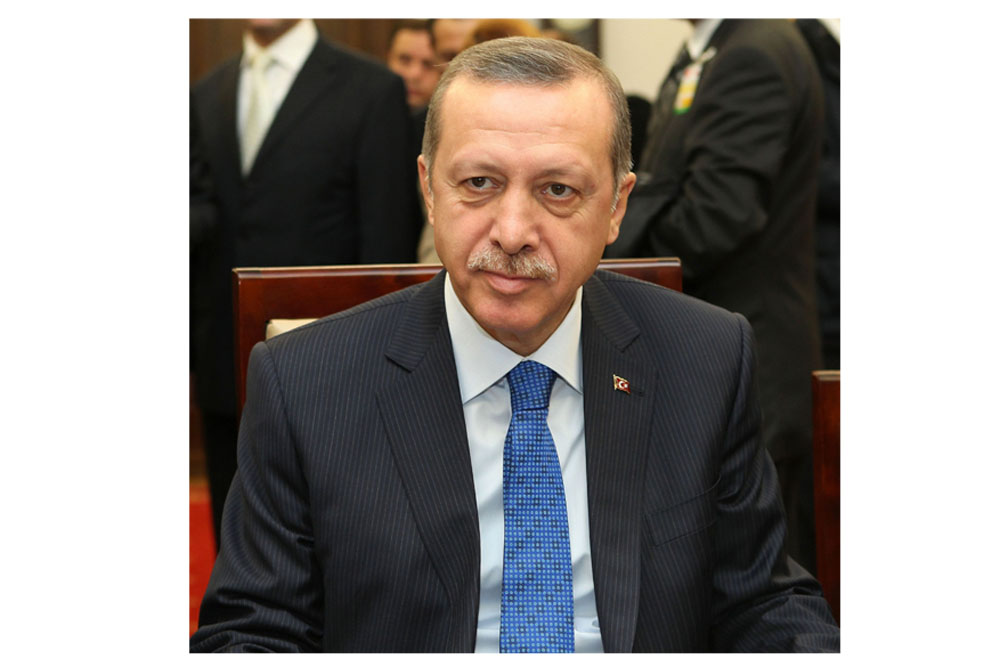

On April 17, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced victory in his campaign for a constitutional referendum that will have a profound impact on the balance of power in Turkey’s government.

Professor Birol Yeşilada, the endowed chair in Contemporary Turkish Studies and director of the Center for Turkish Studies at Portland State, said he fears for the future of Turkey.

“We cannot talk about any legitimate degree of democracy in Turkey any longer,” Yeşilada said. “Anybody who says otherwise needs to get their head examined.”

The constitutional changes will replace Turkey’s parliamentary system of government with a presidential system, abolishing the office of the Prime Minister and giving Erdoğan sweeping powers to appoint judges and ministers.

However, unlike the presidential systems in the U.S. and France, under the new constitution Erdoğan would be the de facto head of both the legislative and executive branches of the government. The independence of the judiciary has also been all but eliminated, with the courts being increasingly unwilling to stand up to Erdoğan.

Following the referendum results, Turkey’s high election board rejected legal challenges by the country’s main opposition parties, who called for an annulment of the referendum results. Cited in the challenge was the last-minute decision by the board to accept potentially hundreds of thousands of unstamped ballots, a decision which appears to be in direct violation of Turkish election laws.

“I never thought this was going to be a fair and free referendum, but this was over the top,” Yeşilada pointed out. “He has been campaigning for a yes vote, he’s been wanting these changes even though he has been running the country like a sultan.”

The Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe issued a report that highlighted myriad irregularities surrounding the referendum campaign, including “the dismissal or detention of thousands of citizens,” “one side’s dominance in the coverage and restrictions on the media,” and “late changes in counting procedures.”

Leading up to the vote, a climate of fear and intimidation was created by Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) during a state of emergency announced after a failed coup attempt in July 2016.

Amanda Sloat, former Deputy Assistant Secretary for Southern Europe and Eastern and Mediterranean Affairs at the State Department, came to Portland State earlier this month. While discussing her diplomatic experience and time working for the State Department and as Senior Adviser to the White House Coordinator for the Middle East, she described the complicated history of Turkey’s descent into autocracy.

A key figure in that history is Fethullah Gülen, a Muslim cleric and former head of an Islamic sect based on Sufism, currently living in exile in the United States.

“When Erdoğan came to power in 2002, and this is something the Turks don’t talk so much about, Erdoğan and Gulen actually worked very closely together,” Sloat said.

Gülen and the transnational religious and social movement he started have been accused of instigating the coup. While the extent of Gülenist involvement remains unclear, the crackdown following the coup saw tens of thousands of arrests, which included thousands of judges, prosecutors, academics, and teachers. Turkey currently has more imprisoned journalists than any other country in the world.

“Today, anybody you don’t like in Turkey, all you have to do is complain that they belong to a Gulenist organization, and you’ll ruin their lives,” Yeşilada explained. “This is very scary.”

After the establishment of the modern Turkish state in the 1920s, organizations like Gülen‘s were driven underground as a new secular republic formed from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. Erdoğan and Gülen’s original shared objective was to get the military out of power.

Sloat went on to describe how attempts to undermine Turkey’s secular institutions and the military eventually devolved into a power struggle between Gülen and Erdoğan.

“This is no longer an attempt of outright Islamization of a secular republic,” Yeşilada later explained. “That was the agenda earlier, but now it’s beyond that. It’s all about the personal ambitions of one man.”

“Interestingly, you have some people that would be OK with Erdoğan having this degree of power,” Sloat said. “But they wouldn’t necessarily be OK with the unknown person who comes after Erdoğan having the power.”

According to Yeşilada, attempts by Erdoğan to stir up nationalist sentiments with slogans referring to “Neo-Ottomanism” betray a lack of understanding of history.

“As someone who has studied Ottoman history, I can tell you that AKP people who claim to be neo-Ottomanist have no clue what the real Ottomans were like. Ottomans ruled over a multi-ethnic, multi-religious empire. It wasn’t about Islamization. It wasn’t about promoting Sunni Islam. That happened toward the end of the empire, when it was collapsing.”

Erdoğan has continued to distance himself from other European nations. Turkey is still a member of the Council of Europe, which means that it falls under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights. While it’s possible that a suit could be brought against the government for violating Turkish citizens’ human rights, Erdoğan has already hinted that he will disregard any attempt by outside authorities to intervene.

“They’re anti-NATO, anti-EU—they used the EU as a vehicle to diminish the powers of the Turkish military,” Yeşilada explained. “Look who their best friends are: Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood, Saudi Arabia, Gulf states—not secular Arab states.”

Daily protests have followed the referendum results, and despite dozens of arrests, hundreds of people throughout cities in Turkey have continued to take to the streets.

“They’re calling for justice and they’re getting beaten up and arrested,” Yeşilada said.

He went on to say that he was impressed with the degree of opposition that has emerged and the willingness of demonstrators to question and take legal courses of challenge without resorting to arms.

“I’ve heard followers of Mr. Erdoğan—I‘m not just talking about ordinary people, I’m talking about party leaders, administrators,” Yeşilada went on, “who say, ‘If there is an opposition that resorts to violence, we will just crush them.‘”