In case you don’t already know this from my previous columns, I like words. Language is a really neat thing, and because of its constant evolution it never stays the same for long. (Except apostrophe rules—those don’t change, so please stop pretending they don’t exist.)

Within the last few years, the literary scene has traversed away from the broad, public face of the major publishing houses toward independent presses and self-publishing instead. With this, a number of notable quarterlies and serializations have sprung up (some names I’d like to drop are Shabby Doll House and Muumuu House, but countless others exist as well). I’m a proponent of nearly any kind of independent publishing or literature, mainly because that’s where you’ll find the most raw and real work.

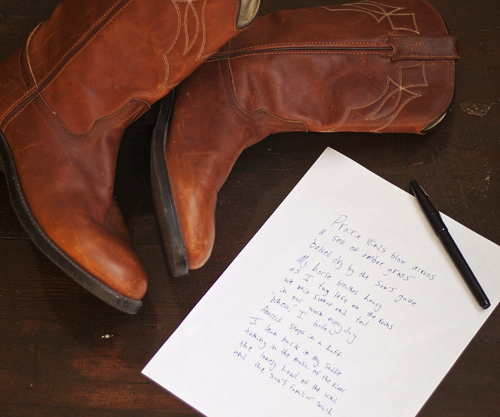

A few weeks ago, I discovered a new subgenre of poetry: cowboy poetry. Because I spent my formative years in a town in which there were “cowboys” (I use quotations because the cowboys from my high school seemed more concerned with who drove the biggest truck or who had the best chewing tobacco than with ranch life) and many of them were less-than-desirable company, I had a few doubts about the craft. However, after doing some research and reading a little bit of this “cowboy poetry,” I was pleasantly surprised.

Generally speaking, cowboy poetry is written through the eyes of ranch hands, “buckaroos” and the like. The poems vary in length but contain traditional poetic devices like rhyme, meter and line breaks, and all provide reference to, as The Oregonian calls it, “old Western traditions as well as the challenges of modern-day ranching.”

Despite that most of the poetry we’re familiar with was written by men—I dare you to think of one female poet you read in high school, aside from Emily Dickinson—we like to assign feminine voices to poetry. That isn’t the case within the cowboy poetry community. Here, most of the writers are men, and therefore nearly all the poetry is automatically considered masculine. Given the subject matter, that’s really—and sadly, I suppose—not the case.

More recently, however, a growing number of women have been participating in cowboy poetry. The Oregonian recently profiled one poet, Jessica Hedges, who at only 24 is already going to Nevada to perform at the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering.

Hedges spends a majority of her time working on a ranch in Burns, Ore., with her husband, taking care of their son and writing her poetry. She also just published her second poetry CD, Buckaroo Woman, Unconfined.

What sets Hedges’ poems apart from the male-dominated scene is that she interweaves themes of femininity into stanzas detailing ranch life and cattle-wrangling. Her subjects include “the pain of losing a beloved horse, to the strength and beauty of a buckaroo woman, to the annoyance of suiting up in full winter gear, then realizing you need to relieve your bladder.”

This particular poetry scene gets smaller every year, as new generations move away from the ranching and cowboy lifestyle. While this is a product of the times, it’s also a disheartening fact that this scene, so honest and hardworking, is dwindling.

Fear not, though; as The Oregonian said, “the lifestyle’s presence in American folklore is as strong as ever.” While the poetry might not be doing much to save the lifestyle itself, it’s “brought attention to the occupation and helped preserve the traditions.”

Whatever your preferred poetry tastes might be, give some of this Western-infused writing a shot—you might like what you find.

Cowboy poetry readings mirror traditional poetry slams in that everything is recited from memory. Some of Hedges’ work is available online, including recorded performances. In the videos, she stands confident in her full rancher uniform and recites really beautiful poetry about the lifestyle she leads. What’s so nice, and a bit surprising, about the poetry, is how easily the reader or listener can identify with the poems, even if he didn’t grow up on a ranch or have any prior knowledge of the cowboy lifestyle.

While cowboy poetry doesn’t exactly fit into the more contemporary form of say, slam poetry, or even the mutually inclusive and exclusive “alt lit” community, it retains the essence of poetry as a beautiful art that we can share with one another, and it doesn’t have to be about name-dropping or whose metaphor is longer. The beautiful thing about poetry is its transference and accessibility; this isn’t Ezra Pound, after all.

For some of Jessica’s poetry, check out her website:

jessicahedgescowboypoetry.com:. For now, here’s an excerpt from Buckaroo Woman, Unconfined:

There ain’t much I ask for from God and this old world

Always been a pretty easy keeper so I guess

Never been one for dresses or ballet slippers that twirled

I’ve just tried to live by the motto that more is less.