Allies and members of Portland State’s LGBTQ community gathered in the newly renovated Queer Resource Center on Wednesday, Oct. 14 for a conversation dedicated to “Troubling the Coming Out Narrative”—one of the many events featured in Coming Out Week, which started on the previous Sunday, National Coming Out Day.

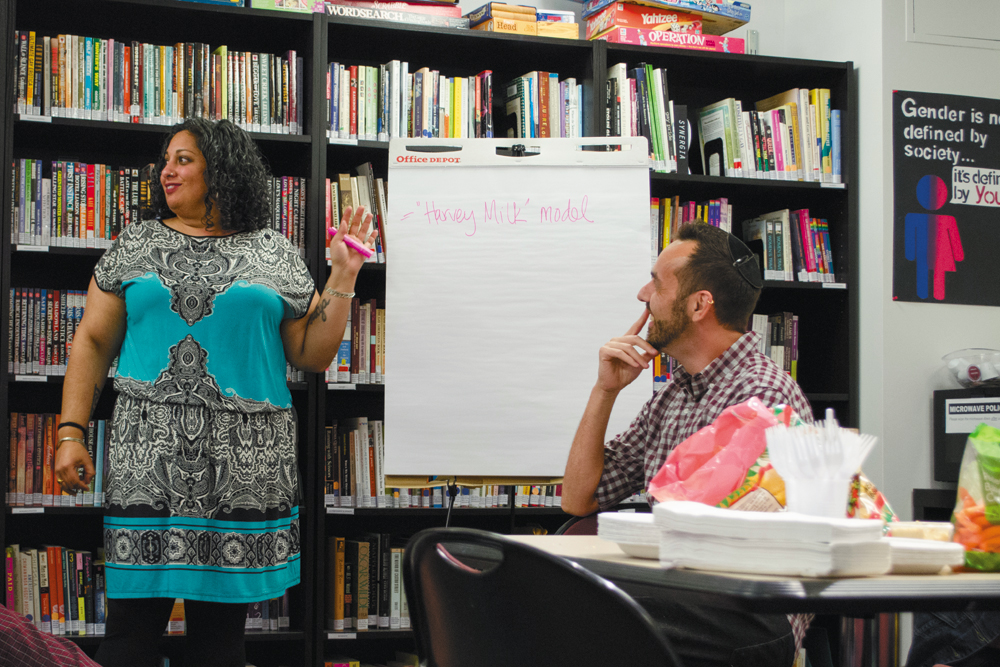

Doctors Gita Mehrotra and Ben Anderson-Nathe, professors in the PSU School of Social Work, facilitated by explaining previous models of coming out and posing questions to the large group.

The first paradigm of coming out was informally referred to as the “Harvey Milk model,” after the first openly gay person was elected to public office in California in 1977. Craig Leets, the QRC coordinator, recalled the film Milk in which Harvey Milk was portrayed as claiming that everyone needs to come out immediately to everyone they know.

The problem is that he encouraged coming out “without any sort of contextualizing about what the repercussions or impact might be for those people,” Leets said. “It was just ‘Come out loud and often.’”

On the other hand, not coming out has often been considered by some as a kind of betrayal of gayness, Anderson-Nathe added.

“It’s also a discourse/narrative that obscures the risks people often experience when they come out and over-assumes that it’ll get better once people are out,” Anderson-Nathe said. “For lots of people—including but not limited to many people of color, poor folks, genderqueer or trans folks and people from collectivist backgrounds–this simply isn’t true and the expectation to come out puts people in a tight spot from which there’s no easy escape.”

The group identified the problem with this in-or-out dichotomy as not allowing space for complexities.

“In our contemporary discussion of coming out, there’s an assumption that everyone should come out and that coming out is the marker of being an empowered and healthy LGBTQ person,” Mehrotra said. “But the reality is that for a lot of people it’s actually much more complex than that. I think we need ways to understand that it’s much more dynamic.”

Some view coming out as one of several critical stages in a process toward obtaining a healthy identity. Anderson-Nathe described how being visibly gay and proud is treated as a necessary, but temporary, act before one is ultimately integrated back into the dominant culture.

However, this model reduces a variety of individual situations and experiences into a narrowly defined and linear path, and ultimately works within the dominant heteronormative power structure, instead of disrupting it.

“Coming out puts a lot of onus on the individual to be the person who’s the actor,” Mehrotra said. “The individual who’s queer has to come out, but there’s not really a questioning of the structure that creates the circumstance where someone even has to come out.”

Some are encouraging the need to acknowledge and talk about the conditions of homophobia and transphobia.

Leah Parker, a PSU junior, resented that the act of coming out is about making others more comfortable.

“They want you to be out so they don’t have to think about it,” Parker said.

Ironically, Mehrotra noted that when Milk advocated coming out thirty years ago, it was to intentionally make people uncomfortable, whereas now labeling someone is an attempt for them to feel more comfortable.

“We don’t question the closet, we question the person in it,” Mehrotra said.

But how does one remove the burden of coming out? In order to do so, Mehrotra encouraged those involved in the discussion to create communities that accept and understand all different types of gender identities and sexual orientations.

“If you change the culture to where there’s very clear acceptance and openness and understanding of the range of gender and sexual identities and experiences, I think it changes the onus on the person,” Mehrotra said.

Even though many participants voiced the need to define their own parameters and methods of coming out, which challenged the pressure to be marked by their sexual orientation or gender identity in prescribed ways, that wasn’t to say visibility wasn’t important. In fact, members of the audience agreed that it can be critical for survival.

The discussion also addressed how some within the LGBTQ community are not represented by or included in the current coming out narrative, which tends to be dominated by white gays and lesbians that may otherwise occupy positions of privilege in their lives.

“A lot of critiques are coming from LGBTQ folks who might be more marginalized in other ways,” Mehrotra said. “So you’re talking about queer people of color or trans people of color or poor queer folks who have a different set of contextual circumstances to have to continue to navigate and negotiate in their coming out process. I think those voices getting amplified is part of needing to challenge this narrative more explicitly.”