Not many people can say that they’ve influenced an entire section of the internet. Local cartoonist Allie Brosh is known for creating the “Alot” monster and “All the things!” memes, but apart from those, she’s amassed an impressive body of funny and relatable work.

Touchstone Publishing has just released a collection of Brosh’s webcomics that includes new material, titled Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things That Happened.

Though unwieldy, the title gives an accurate idea of Brosh’s range of storytelling. Loosely arranged into color-coded segments (the side of the book looks like a stack of construction paper), the tales told range from observational dog humor to frank self-examination and goofy childhood memories.

Originally appearing on her website starting in 2010, Brosh’s webcomics read more like an illustrated blog. Panels are often separated by a paragraph or two of expository text, with occasional handwritten scrawl in the place of tidy speech bubbles. It works in favor of the sketch diary motif, which is especially effective when Brosh starts to get intensely personal.

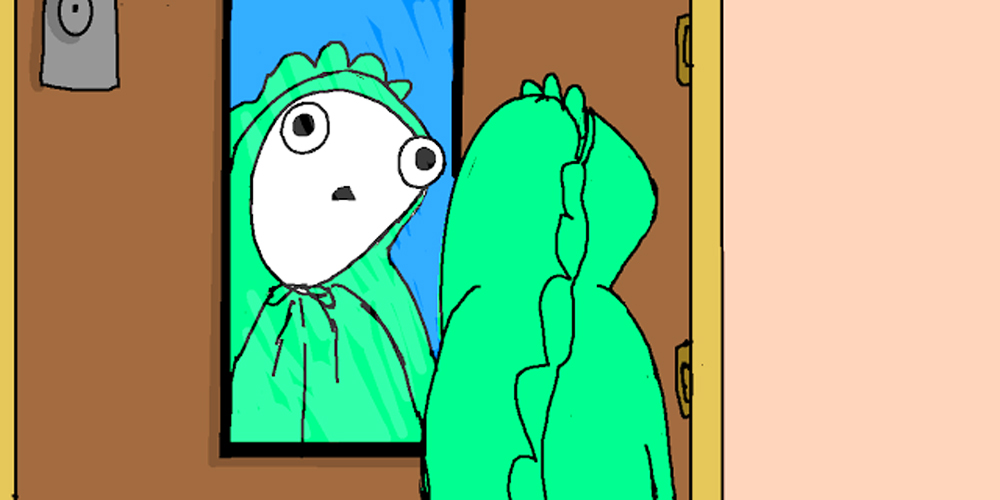

Hyperbole and a Half is known for its crude and—to use a term from the internet, “derpy,”—drawings. The stories are illustrated with boxy characters one notch up from stick figures, filled in with solid colors. Anyone who’s messed around with the stock Windows art program will recognize the spray paint tool utilized to fill in a dog’s coat.

The rough sketches might initially appear as though they could have been drawn by anyone, but there’s a layer of invisible skill here that engages the reader further without losing its humble appeal. Brosh knows just the right perspective and framing for her advanced doodles. She also has the rare and uncanny ability to induce laughter using only a vacant facial expression.

Dissecting humor is tough, especially in a book like this where laughing at juvenile poop jokes only makes you feel younger and dumber than the children making the juvenile poop jokes on the page. Brosh disarms the reader with crass gags that can be, at any moment, a self-deprecating poke or brutal self-flagellation.

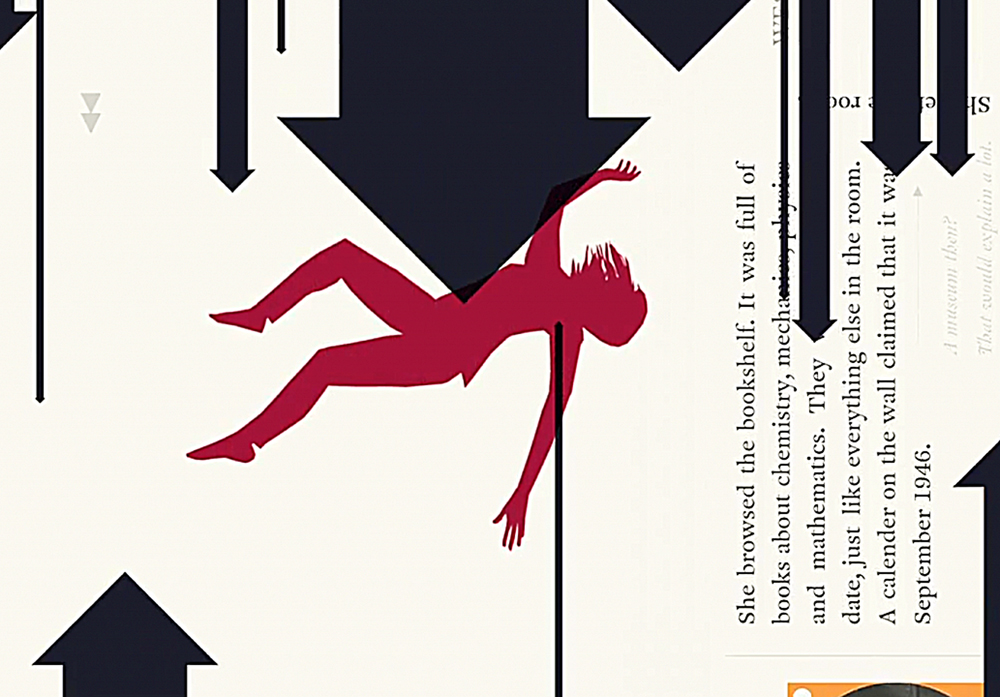

Even when Brosh does get serious, she still finds a way to be funny while getting her point across. The centerpiece of the book is probably “Depression,” a 50-page exploration and explanation of her hiatus from her webcomic. Through her depictions of fruitless conversations and spontaneous non-epiphanies, Brosh gives a play-by-play of what it’s like to live in the doorless room of depression. We see friends unable to process that she can’t just snap out of it, as if she hadn’t already tried that. The otherwise intangible inner struggle seems effortlessly visualized with dirty sweaters, black holes and frowny faces.

The chapter gives voice to the suffering with the feeling that there’s no way out. Not only is it cathartic for those afflicted, but it manages to explain the problem in an easily understandable way to loved ones with a friend or family member dealing with depression. It’s a Herculean task to have accomplished, especially with MS Paint.

Opposite the large scope of universal plights are the stories about Brosh’s dogs. Most of these tales attempt to understand the behavior of her pound-rescue mutts and the conversations they might have if they spoke human language.

“Q: Should eat bees?

A: No.

Q: But… never bees?

A: No, you should never eat bees.”

These stories are especially hilarious to animal lovers, but by the end of the book they start to wear thin. The bizarre and memorable childhood anecdotes play much better over the course of 350-plus pages.

Except for the new material included in the book, you can read a lot of these stories, including “Depression,” for free online, at her blog-spot. You would be encouraged to do so if you’re interested in Brosh’s work, but you might find it easier curling up with a good book than a bulky and awkward laptop. Visit Allie’s blog-spot at hyperboleandahalf.blogspot.com