The selection process for new resident assistants has finally begun. Many eager students will get the opportunity to work for University Housing and Residence Life come the 2014–15 school year, and my heart goes out to them. It can be a fulfilling and rewarding job, but also one that lacks professionalism, security and organization.

I went through the six-month-long hiring process and the two-week-long fall training, and was on the job for a month before my contract was terminated. While my time on staff was a bit unorthodox and ended not long after it began, what I saw and experienced left me with no feelings of nostalgia toward my time spent with UHRL.

There are many things about the job I enjoyed. I loved my co-workers, my supervisors and the people I met while on staff. However, the job is a task that should only be undertaken by those who are deeply dedicated to it and who are willing to put up with all of the difficulties, trials and negativity that accompany it.

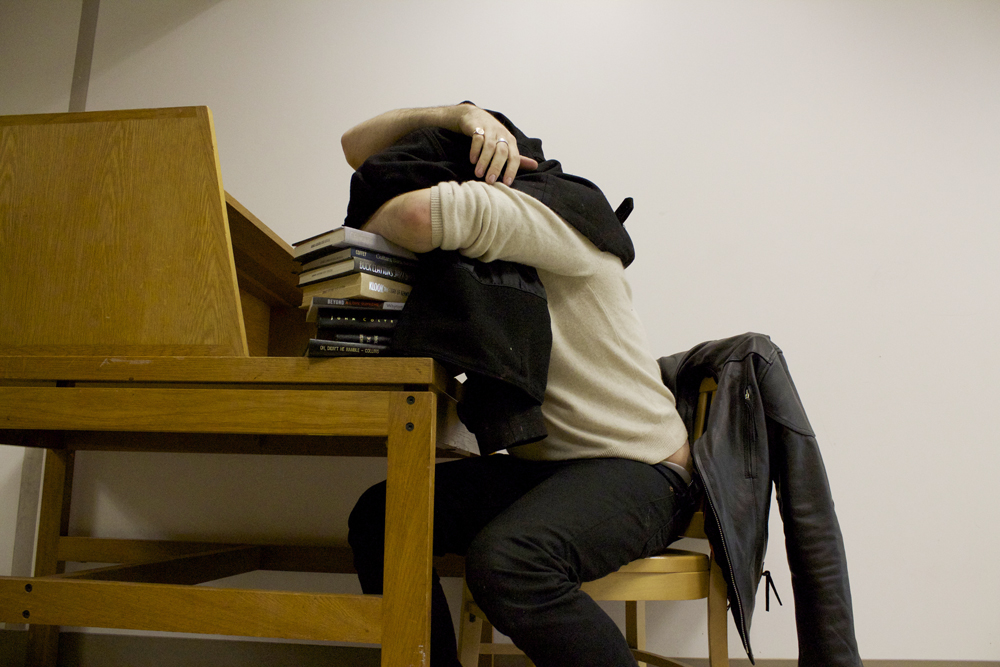

The job itself is a sacrifice of not only time, but of personal commitments, close friendships and school dedications. Some RAs can pull it off. They work multiple jobs, maintain their friendships and do well in school. But for a good amount of people, the job is physically and mentally draining, and it’s not unusual for RAs to leave midyear.

With weekly staff meetings, programs, being on call, required office hours, one-on-one meetings with supervisors and all of the miscellaneous stuff that goes with the role, it can feel like you are on the job 24/7. To some, this may sound appealing, but to others it is more of a curse than a blessing.

Most people don’t like it when work follows them home. When you’re an RA, not only do you live at your place of employment, but you can also never separate yourself from the obligations of the job. Not only that, but your co-workers incidentally become some of your closest friends. It goes beyond mere accidental proximity, as RAs are practically their own subculture on campus. They understand the same jokes, share many of the some difficulties and spend large amounts of time with one another.

However, such interpersonal relationships don’t exist without difficulties.

Gossip amongst UHRL staff is like a plague. It’s unavoidable and inescapable. RAs gossip about everything and everyone: fellow co-workers, supervisors, residents and incidents. Tensions run high, people get angry and with so many different ideas, approaches and opinions it’s difficult to always be at peace with everyone. Like any stressful workplace, it’s better to keep your mouth shut and say nothing, because odds are it will be repeated.

When I originally applied to become an RA, I wanted to be a person my residents could rely on and be friends with. However, this was difficult when your employers explicitly say to “be friendly, but don’t be their friend.” Rather than feeling comfortable around residents, I often felt like I was stepping on eggshells, trying not to say the wrong thing while still attempting to treat them like human beings. This inability to be myself, share my experiences and be open with my residents made every interaction feel fake and somewhat dishonest.

Not to mention, in a job that demands such professionalism, there is a major lack of procedural integrity among RAs. I can honestly admit that some of the greatest violators of policy are the RAs themselves. Everything from drinking when and where they’re not supposed to, owning candles, hanging stuff from their ceiling or violating quiet hours—it’s all done on a regular basis by those who are employed by UHRL.

There’s also a troubling contrast in how RAs approach their job. Some RAs take their job way too seriously, and some of them not seriously enough. You’ll have RAs who are strict and others who are too easy going. There’ll be RAs who care about their job and those who are just in it for the benefits. Such a polarization of approaches makes it difficult to maintain any middle ground. You are often pitted against your fellow co-workers by residents who have been treated unfairly, and even if you agree with them, you can’t take their side.

The gauge for how policy should be enforced seems like it would be black and white, but there is a lack of any consistent, all-encompassing approach. I have seen residents get away with infractions like throwing a fire extinguisher out a window and I’ve seen residents get documented for possession of alcohol for simply having empty beer boxes that they were going to use for an art project. I’ve known RAs who blatantly turned a blind eye to marijuana use and RAs who aggressively sought out policy violators. Fair treatment is something that is emphasized during training, but the practice is far from perfect.

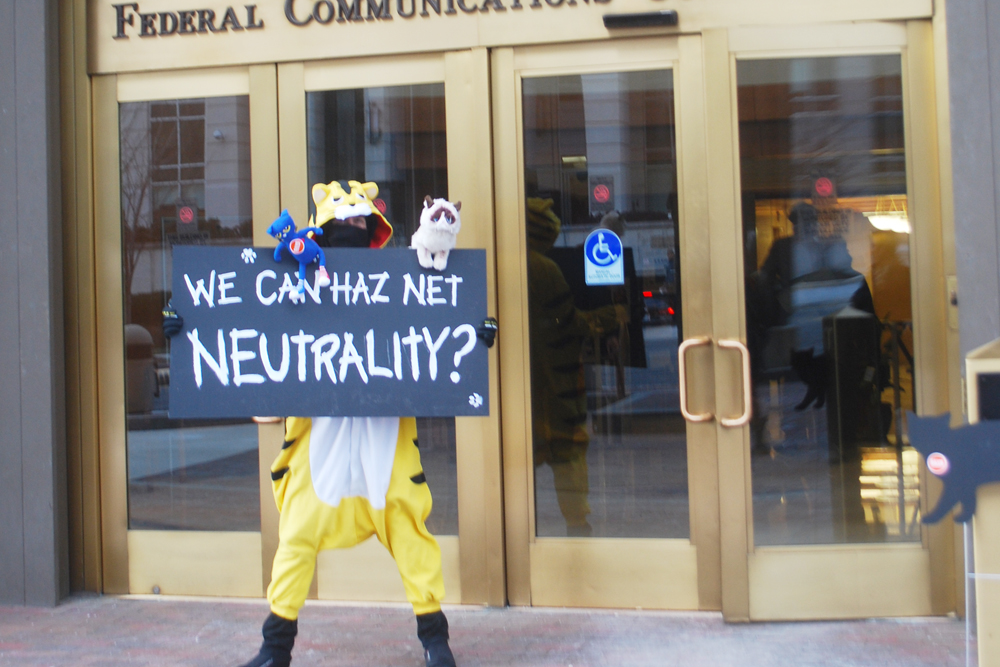

Finally, the fall training was arguably the most tiresome and difficult aspect of the hiring process. Many people return to the job year after year, and I thought I was going to be one of them, but fall training changed my mind. While I appreciated the knowledge I gained, the time commitment was extremely demanding and many of the presentations were biased in ways that pushed a progressive social agenda where dissension could possibly threaten your employment.

Let me finish by saying that I have nothing but love and respect for my former co-workers, supervisors and department heads. They are all good people and do their jobs well. While I had issues with the job, it doesn’t mean that people shouldn’t do it. However, much of what I have mentioned is what you don’t learn in the RA class or fall training.

For those who are applying to become RAs, good luck, and to those who are currently RAs, I wish you all the best.

Many people are not cut out for the job, but more often than not, the job is just not cut out for some people.