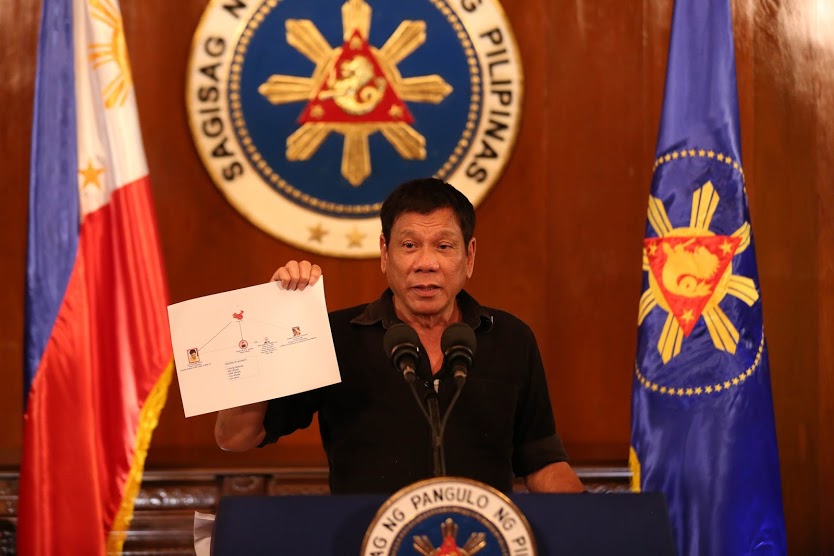

Since Rodrigo Duterte became president in June of 2016, the Philippines has endured an ongoing drug war resulting in the killings of many citizens both guilty and not guilty of drug abuse.

With the plan to slaughter anyone and everyone addicted to or involved in the use of illegal drugs, Duterte has taken an aggressive force to stop the illegal drug use in the Philippines. As time has passed, the general public has begun to question whether or not these tactics have been successful.

According to International Studies professor Shawn Smallman, Duterte’s tactics started out relatively successful among his supporters. “In the first six months of his administration thousands of people died,” Smallman said. “Many were gunned down by killers on the backs of motorcycles, or they were shot by police upon the mere suspicion of doing drugs.”

Smallman went on to explain that despite the death toll and suffering caused, many drug offenders surrendered themselves to the police, and people perceived that the policy was effective. As of late, however, the unending violence has caused public support for Duterte’s war to wane.

According to the New York Times, in August of 2017 the Philippines logged their deadliest week since the drug war began, with 58 people killed in just three days. With over a year of ruthless killings, citizens and human rights organizations have begun fighting back against Duterte’s tactics.

PSU alumni Nikki Dela Rosa, Joseph Gonzalez and associate professor Alma Trinidad were part of a mission trip to the Philippines shortly after Duterte took office. They’ve compared the Philippines they saw then with what they are seeing happen now.

“The public opinion has changed drastically from the time he was inaugurated a year ago,” Gonzalez said. “Originally the public seemed very supportive of his next steps to address poverty, agrarian reform, industrialization, and the abusive relationship between the Philippines and the U.S. Today, the killings have rose and more and more people are becoming outraged by his lies and unfulfilled promises.”

While forceful action to combat illegal drug trade is not uncommon across the globe, including the death penalty, there are key differences between what is happening in the Philippines and what takes place in other countries. For example, both Singapore and China impose the death penalty on drug offenders, but this differs greatly from the killings taking place in the Philippines.

“What is different is that deaths [under the death penalty] take place within a legal framework in which the accused are able to represent themselves in judicial proceedings,” Smallman said. “In general, in Europe there is a movement toward harm reduction, whereas Asian nations are more likely to adopt stiff penalties for drug usage.”

According to Smallman, the movement toward harm reduction views drug use as a public health issue, focusing resources on outreach to drug users and treatment rather than criminalization.

In today’s political climate, a number of major global issues have pushed the Philippines drug war to the bottom of a lot of popular media sources. “The violence in the Philippines does not directly threaten Americans or Europeans, so it has received less attention from media outlets internationally,” Smallman said.

Dela Rosa disagreed with Smallman in that she believed there was adequate media representation. The lack of action from students on campus disappointed her, however.

“The drug war in the Philippines is receiving enough accurate media representation here, especially online,” Dela Rosa said. “It’s just a matter of what we do about the information that makes it stand out. Rising up to these situations is easier than we think.”

Organizations in Portland such as Anakbayan, Gabriela, PSU Kaibigan, and Portland Committee for Human Rights in the Philippines are addressing these issues [and working] to end the extrajudicial killings in the Philippines by the drug war campaign of the current President Duterte’s administration.”

The impact that more attention and involvement from nations such as the United States could have on the violence in the Philippines is immense. “Until now, President Duterte has not faced sufficient international pressure to end the violence,” Smallman said. “If there were enough popular protests against his policy elsewhere, it might lend key support to those people in the Philippines who are working to end the ceaseless violence and arbitrary killings.”

Trinidad agreed the citizens of the United States and PSU students have a responsibility to get involved with this issue and educate themselves on the topic. “The drug war is masked as a tactic for power and control,” Trinidad said. “We must continue to educate ourselves and identify ways on how this impacts us as global citizens. We are all connected.”