Those who follow boxing will be quick to remind you that no matter how dire the situation may seem, a fight can change with a single swing. “A puncher’s chance” is the phrase most often thrown about as some poor soul wobbles in a reverse diagonal with his white trunks stained red, through 10 rounds, unable to connect with the heavy right hand that could nevertheless arrive at any moment.

The long con, part II: stick and move

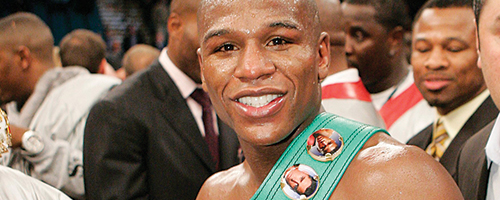

COURTESY OF theyfb.com

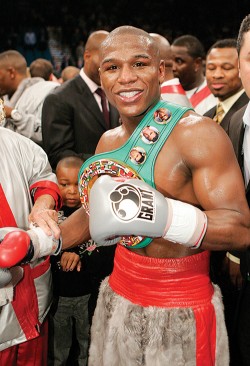

FLOYD MAYWEATHER’S record is 43-0. The fight everyone wants to see would pit him against Manny Pacquiao.

Those who follow boxing will be quick to remind you that no matter how dire the situation may seem, a fight can change with a single swing. “A puncher’s chance” is the phrase most often thrown about as some poor soul wobbles in a reverse diagonal with his white trunks stained red, through 10 rounds, unable to connect with the heavy right hand that could nevertheless arrive at any moment.

The sentiment is absolutely correct. But there is another axiom, which states, “All things being equal, in a fight between a boxer and a puncher, pick the boxer every time.” It is this concept that defines what the sport, when practiced at its highest level, was truly meant to demonstrate, and it is the principal reason that Floyd Mayweather will take into his next fight a record of 43 wins without a single loss. It is not, however, the only reason.

In a business that depends as much on a fighter’s marketability as his capability, Mayweather has maximized his potential in both regards. After spending the first half of his career piling up victories while never quite managing to infiltrate the mainstream, Mayweather began his transformation from a slick and successful gym rat to the default villain in every bout in which he takes part.

Just how much this antagonistic public persona reflects the true nature of the routinely controversial champion is a question for which there is no sufficiently convincing answer. It is the sort of question that likely can never be answered with any measure of certainty, and at this point, it is no longer particularly relevant.

What matters is that, regardless of the contributing factors that led the boxer to his official conversion from “Pretty Boy Floyd” to “Money Mayweather,”

the return on his investment was immediate and undeniable. He is now among the highest-earning American athletes, and one of the only two names recognizable to anyone outside of boxing’s diminishing sphere of influence.

The Grand Rapids, Mich., native is a pay-per-view star all on his own, the automatic A side of any event that bears his name. And even if many people tune in only to root for him to lose, that’s just fine by him. Mayweather figured out long ago that it ultimately makes no difference—they’ve still bought the ticket.

Simply providing the counterpoint in a manufactured good vs. evil promotional setup is not enough to build a career on, though, and so Mayweather has gone to great lengths to ensure that his spotless ring record is as much the focus of his ongoing marketing campaign as the sneering and contemptuous sound bites he provides on cue. He wastes no opportunity to bombard his potential customers with the slogan “43 and 0,” and many would say that he has done a bit too much to guarantee that the loss column remains unblemished.

This is where plans for a long-awaited and endlessly speculated-on showdown with Manny Pacquiao hits the first real snag, and it is the most frustrating aspect of the entire ordeal, because let’s be clear: It cannot be adequately argued by anyone who watches boxing on a regular basis that Mayweather is not the most talented boxer alive.

If one were to construct a boxer from scratch, tossing in all the attributes necessary for long-term survival in a fastidiously regulated but fundamentally barbaric trade, the chances are good that he would look a whole lot like Mayweather. He is more purely gifted, more technically proficient and more disciplined than anyone else on the planet currently holding a license to beat other men senseless.

Like Pacquiao, Mayweather has no serious threat at welterweight. The problem is that he has never really allowed himself to be threatened. While Pacquiao made his name first by steamrolling through the deepest generation of Mexican fighters in history and later by taking on bigger, more dangerous opponents who were at or near the peaks of their careers, Mayweather has few high-profile scalps on his resume who could be said to have been in their primes when he defeated them.

Apart from a dominant performance against the late Diego Corrales back in 2001 and a tougher-than-expected decision against a resurgent Miguel Cotto in May, Mayweather cannot begin to lay claim to the same level of competition as his contemporaries. There are plenty of big names to be found in his past fights, but they were, almost without exception, either coming up (sometimes significantly) in weight to collect the biggest paycheck of their careers, or much closer to the end of their days as professional fighters than Mayweather would ever admit.

Pacquiao, of course, was supposed to be the great exception, the only sanctioned boxer with any chance of troubling the five-division champion. The Filipino’s tireless attack, awkward movements, fast hands and knockout power are considered to be the only conceivable antidote to Mayweather’s unmatched reflexes and extraordinary defense and adaptability. Pacquiao’s record—losses and all—also speaks for itself, albeit in a completely different way.

If ever there were a chance to settle the pound-for-pound argument once and for all, and bring boxing back into the conversation for all those fans who long ago disowned it, this is it. It would be the most difficult test, and by far the biggest win, of either fighter’s career.

And despite all that, if the two stepped into the ring tomorrow, Mayweather would undoubtedly be the odds-on betting favorite—just as he would have been at any time since the notion of a Pacquiao fight was first proposed. Even a loss would thrust Mayweather into the mainstream consciousness in a way he could never possibly achieve otherwise. And a victory—however close or disputed—would be the single defining element of his career, one that elevated him from his status as the most talented boxer alive to one of the greatest boxers who ever lived. It’s the sort of distinction Mayweather adamantly refuses to make when assessing his own legacy, and it certainly hasn’t done much to stifle his wages up to this point. It will be up to him to decide whether or not that is enough.

To read “The long con, part one: business as usual,” visit psuvanguard.com