With talk of an impending strike reaching a fever pitch, an email last Friday from Portland State president Wim Wiewel told students that spring term courses and graduation dates will remain on track no matter how contract negotiations progress over the next month.

Faculty in the American Association of University Professors recently declared an impasse and soon after scheduled a strike authorization vote that will take place today and tomorrow, March 11–12.

In his email, Wiewel did not offer details as to how the university plans to temporarily replace up to 1,200 professors, instructors and academic professionals in the event of a strike. He promised that “details will be announced in a timely fashion.”

“Our job is to make sure that nothing gets in the way of students pursuing their academic goals, and we will do everything we can to make sure there is no interruption,” Scott Gallagher, PSU’s communications director, has stated.

Many faculty and students claim that it is in fact the administration’s lack of cooperation that has brought the university to this point of instability in the first place.

“We don’t want to strike but we will if we have to, in order to provide the kind of high quality education to which we are committed,” explained instructor David Osborn.

The website “Fighting for the Future of PSU,” representing a coalition of faculty, staff and students in support of the AAUP in their current bargaining process, says that, “After 10+ months of negotiations where the administration has been dragging their feet on issues AAUP members care about, a strike may be the only way to move forward.”

Getting here

Every two years AAUP renegotiates their biennial contract with the administration. Negotiation for this biennium began April 24.

By August, faculty were already feeling frustrated at the bargaining table. With their current contract slated to expire at the end of August, it was at that time that AAUP first convened a strike strategy committee.

In September they were put on a temporary contract extension and negotiation continued. However, faculty were surprised that the administration contacted a state mediator as early as October.

“They were unwilling to even talk money until October, so the decision was odd,” explained Mary King, an economics professor and president of the PSU Chapter of the AAUP. “It was a very quick decision, and was understood as an attempt to steamroll the process,” she continued.

On Nov. 19, faculty and students rallied in support of professors’ demands. Starting on the sky bridge between Smith Memorial Student Union and Cramer Hall, hundreds of participants marched to the administration’s Market Center Building and held speeches on the steps.

Two days of mediation in mid-December seemingly made little difference. “Mediation is not as useful as it sounds,” Mary King said. “The mediator just goes back and forth between the separate rooms asking if anyone has changed their mind yet.”

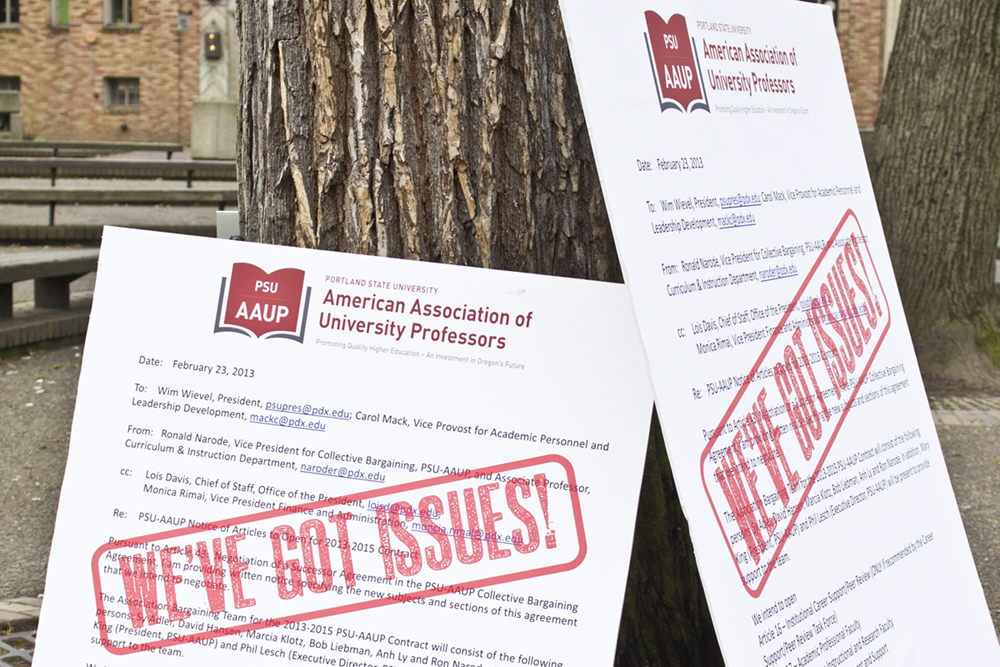

The past month has seen the situation quickly crescendo into crisis mode. On Feb. 7, AAUP filed an unfair practice charge with the Employment Relations Board, accusing the administration of breaking the rules that govern employer-employee relations statewide.

Faculty announced their declaration of an impasse on Feb. 24. According to state law, an impasse may not be declared until at least 15 days of mediation services have elapsed. By that time in February, AAUP had already been in mediation for nearly two months.

Labor law dictates that employer and the employees each submit their best offer contracts to each other a week after an impasse is instated. At that point a 30-day “cooling off period” begins, which is a window of time when a strike authorization vote can be held but no strikes may take place until after the month has elapsed.

That puts the earliest day of strikes on April 3, right at the beginning of spring term. However, both the administration and the AAUP declare that they are doing everything possible to resolve a contract before the need to strike, and that they remain optimistic that an agreement can be reached and strike evaded.

“We don’t think we’ll get there,” said Gallagher at university communications. “Every two years we go through this process, and sometimes it is more contentious than others.

“We were disappointed that it [went] to an impasse,” he continued. “We thought we were making progress.”

But faculty see it differently.

“After ten months, forty hours of mediation and ten hours of one-on-one with the chief negotiator, we are stuck,” King explained to a groupd of students at Thursday’s general meeting of the PSU Student Union.

At this point, avoiding a strike would involve the AAUP membership voting to ratify an acceptable contract between now and the beginning of April.

Once the 30 days are up, the administration has the right to impose the contract of its choice. AAUP faculty have the corresponding right to reject that offer and choose to strike.

What are the contracts on the table?

As explained in Wiewel’s campus-wide email, the administration’s final contract offer to the AAUP includes two options.

The first, option A, proposes a 3 percent rise in salary over two years combined with the right of the union to be consulted on change to promotion and tenure guidelines.

The second, option B, offers a larger salary increase than A (4 percent over 2 years) but completely removes the union’s say in changes to promotion and tenure guidelines.

Some, including King, have suggested that presenting two options in a final contract is unusual.

“It’s extremely unusual—perhaps unlawful—to offer possible choices in a last, best and final offer, as it creates a great deal of uncertainty about what contract the PSU administration would impose on the bargaining unit, which they can do at the end of the 30-day cooling off period,” King said.

Gallagher defended the structure of the final contract. “We’ve provided two options because it helps provide them two ways to go. They can determine which part of the overall negotiation is more important to them,” he said.

However, King asserts that neither contract option is ratifiable. “They both involve giving up faculty and academic professional rights in shared governance, and only incorporate token movements toward stabilizing the faculty and a cut in real pay,” she explained.

Indeed, the fact that the strike vote was scheduled so quickly attests to the unpopularity of the administration’s proposed contract.

“We went out and spoke with our members and it was clear that these choices are not very different from the administration’s previous positions,” King said. “We have seen, and rejected, these contracts before.”

King admitted that there are some minor improvements, but that these are just token changes that affect a minority of AAUP members. For example, the new contract slightly improves the status quo for fixed-term faculty. Now those who have worked 5 years will have a 45 percent chance of getting a permanent job, whereas before they would have had to work 6 years.

“A very small number of teachers are actually affected,” King said, calling the measure a “token movement.”

In terms of shared governance, King says that the current contract offers from the administration both take away what AAUP has had for thirty years—namely, the ability to have the last word when it comes to negotiating changes in tenure and pay scale. In the administration’s option A, the right to consultation is retained.

King is quick to clarify that consultation is not the same as being required to negotiate with the union. “They’ve given us nothing but a choice to lose all of it or lose some of it,” she said. “Both choices are below our bottom line.”

Gallagher countered that changes to tenure and promotion already have to pass the faculty senate, and therefore going through AAUP as well is redundant.

Jose Padin, a professor of sociology at PSU and a member of PSU-AAUP, explained the difference between the faculty senate versus the union.

“Through the senate we define standards for tenure and promotion, whereas through our collective agreement with the administration we set a legally-binding safeguard against unilateral changes to these standards by the administration.”

“The faculty senate can be overruled by the president,” King added. Both she and Padin described the importance of the union’s safeguard for increasing trust in the relationship between faculty and the administration.

Padin underlined the significant breach of historical protocol represented by the administration’s desire to remove that union oversight. “Every prior administration going back 35 years has considered it reasonable to sign on to an agreement that provides a legally-binding check against a president’s unilateral usurpation of faculty power,” he explained.

What next?

While the administration hasn’t mentioned specifics regarding how the university will run during a strike, AAUP has made some comments that suggest a strike wouldn’t last for long.

“Strikes in education tend to be short, given the tremendous pressure on both sides to settle,” King said.

“I expect that most classes would be cancelled for the duration of the strike, and that faculty would be working hard to adjust to a shorter term—as we do in summer session—or that we might extend the term by a few days, if need be.”

However, King cautioned, “Nothing is certain.”

“Nobody wants a strike,” she said. “We’d rather be doing the jobs to which we’ve dedicated our lives!”

Editor’s note: It has recently come to our attention that Sara Swetzoff has been reporting on issues concerning the potential faculty strike while also maintaining personal involvement with the Portland State University Student Union—an organization that has come out in full support of the PSU chapter of the American Association of University Professors. The Vanguard recognizes this is a conflict of interest that contradicts our mission to serve as a fair and balanced news source for the PSU community. We apologize for failing to catch this problem before the stories made it to print and have since taken action to ensure it will not happen again.