Whenever a popular novel is adapted into a movie, it seems that readers are always quick to announce how much better the book is. Some people even go so far as to avoid seeing the movie entirely, in fear that it will ruin the experience that they had when they first read the book.

Having seen several poorly adapted films myself (Eragon, I’m looking at you), I can definitely relate to the sentiment. There is nothing worse than getting excited to see an adaptation of your favorite story only to begin watching and realize that your favorite aspects of the book have been changed or the subtle aspects of the author’s writing completely forgotten.

However, just because a handful of movies didn’t do their source material justice, that doesn’t mean that they are all bad. In fact, the number of “bad” movie adaptations is relatively small if you think about it, but they tend to stick in the minds of fans longer than the good ones do.

Somewhat ironically, the argument of the quality of films vs. books is very divided, along the line of film buffs vs. readers. As a reader, if someone were to ask you whether you liked the book or movie version of a particular story better, the answer seems simple, right? “Well the book of course,” you’d say. But is it really that simple?

If you enjoy reading books, you most likely have a fondness for books over other types of entertainment. Yet, aren’t there interesting aspects of film that are missing from the printed version? Sure, the book is able to go a lot more in-depth and provide additional background about elements of the story, but movies are able to provide definite sounds and images that books cannot.

Some film adaptations are quite good and bring a new angle, extra information or the filmmaker’s point of view to the original story – although the jury is still out on The Hobbit. Neither films nor novels are any better at telling a story. There are many great movies that aren’t based on books.

In most cases, books and film are too different from one another to really compare their quality. The limits and strengths of each are quite different. Films tend to be limited by their length, which limits their content. They are intended to be enjoyed in one sitting, and anything over three hours starts to become a bit excessive.

Books are less limited in this way, although it is still possible for an incredibly large book to daunt some readers. However, while some books may do a wonderful job describing the way something looks or sounds, the perception of the image can change from reader to reader. It’s the same way that reading a piece of sheet music is nothing like listening to a live orchestra.

While most people assume books are better because they can provide more room for description and elaboration on certain events, movies are able to offer a visual and auditory element that builds upon the book’s world.

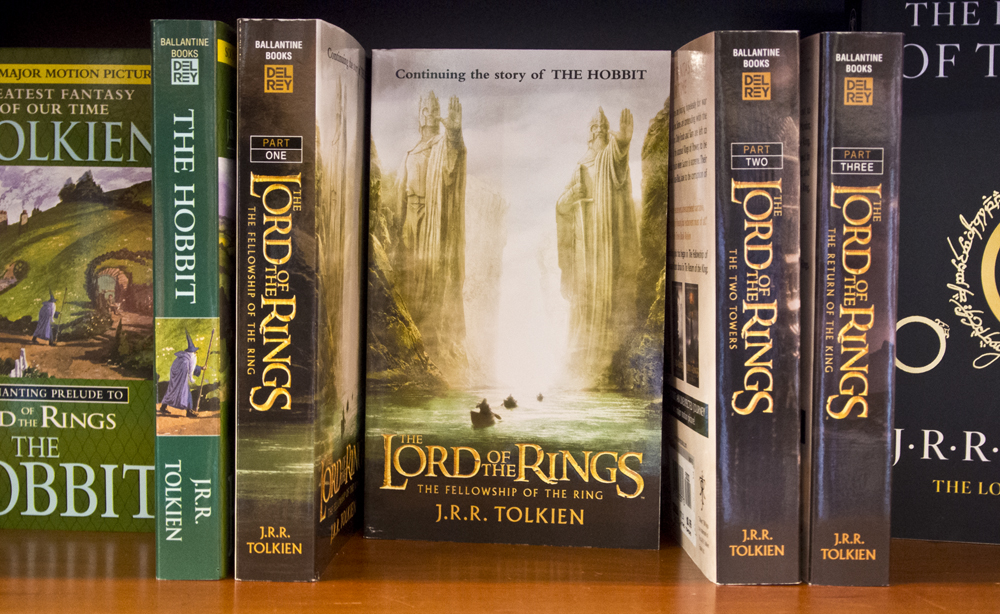

The problem that many readers seem to have is that the film based on a book didn’t fit their original idea of the book when they read it. It can feel like a completely different story when elements of the book are turned into visual elements of a movie. However, as in the case of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, the translation can work out really well, at least for the popular interpretation of the novels.

Whether a book is adapted in exactly the way you imagined it isn’t really the filmmakers’ fault. Books, unlike most films, depend highly on personal interpretation; from the way certain names and places are pronounced, to the more implied motives of a character. It’s impossible to please every reader when the adaptation comes to the big screen.

Aspects that you might have loved about a particular book may be too difficult to translate to a movie format. Rather than trying to compare movies and books, I think we should be looking at stories that, despite small changes, make entertaining pieces of art.

From the intertwining story lines of Cloud Atlas that are apparent in both the film and the book, to the fairytale undertones of Howl’s Moving Castle, great stories can provide entertainment for viewers and readers alike.

While we might try to compare the aspects of the book to the elements of the film, in the end, they are usually good for very different reasons.