It’s hard to forget that all the film’s utopian philosophizing comes on the eve of the biggest war in history. Based on the novel Lost Horizon by English author James Hilton, it is undoubtedly a product of its time: It’s almost as if Capra and Hilton knew.

Adventure on the Horizon

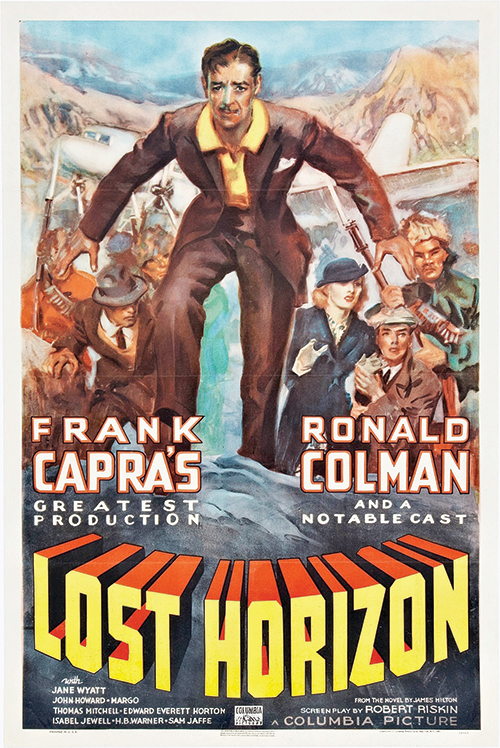

The original cut of Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon was six hours long. The studio actually considered releasing the 75-year-old adventure film in two parts.

Basically, if it were made today, it would be directed by Peter Jackson, filmed on location in Mongolia or somewhere, and spruced up with millions of dollars of amazing computer-generated effects. Then we’d be watching it every Christmas for a couple of years at least.

But in 1937 nobody quite knew what to make of it. It was recut to avoid political connotations in the story, it went $750,000 over budget and it ended longtime friendships for Capra, who was obsessive in his vision for the project.

I don’t think you can compare films made before, say, the late 1970s to those made today. It’s apples and oranges.

Before we had sequels, home video and mass-marketing technology—not to mention greater artistic freedom—so many different considerations and limitations went into making a film.

So it’s interesting to view Lost Horizon—the story of a group of people who travel to a magical valley in the Himalayas—in the context it deserves.

They say that every movie, whether it was made a century ago or last week, is a portrait of the culture and time period of its inception.

The prologue to Lost Horizon begins: “In this time of wars and rumors of wars.” The film begins with Ronald Colman, as dashing English diplomat Robert Conway, rescuing 90 “white people” from Baskul, China, in 1935.

Two years later, Japan invaded China, which began World War II in the East.

It’s hard to forget that all the film’s utopian philosophizing comes on the eve of the biggest war in history. Based on the novel Lost Horizon by English author James Hilton, it is undoubtedly a product of its time: It’s almost as if Capra and Hilton knew.

Conway finds himself escaping on a tiny airplane with a small group of Westerners, including a paleontologist (Edward Everett Horton) and a dying girl (Isabel Jewell), as well as Conway’s brother George (John Howard), who is relentlessly surly and inexplicably American while Robert is as laid-back and English as they come.

They soon find out that their plane has been hijacked by a gun-toting Chinese guy, and they’re stranded in the snowy mountains. Their captor promptly dies, and a group of other “natives” shows up to take them to the magnificent city of Shangri-La.

Yes, that Shangri-La.

Their guide in Shangri-La, a beautiful valley where nobody is cold, is called Chang (H.B. Warner), who speaks on behalf of the High Lama (Sam Jaffe).

It’s interesting to note that Chang is Chinese in Hilton’s novel, but in Capra’s film he looks like a very stoned James Cromwell. Jaffe is playing a character who is notably Belgian, and the two love interests for the Conway brothers, Maria (Margo) and Sondra (Jane Wyatt), are Russian and English, respectively.

There are Chinese people in Shangri-La, but they’re all servants or lower-class “natives.” Everyone of importance in this utopia, which is said to be 1,000 miles beyond the Tibetan borders, is conveniently white.

There are also some very dated and uncomfortable lines about women—notably a conversation between Conway and Chang about what happens in Shangri-La when two men fight over a girl.

I suppose you can’t expect much different from a film made in the 1930s, but it’s funny in a story full of such lofty pontifications on the brutality of man.

But Lost Horizon is a fascinating study of how an epic was once made. Robert Conway is a unique character in that he doesn’t seem bothered by the fact that he and the others have been kidnapped to Shangri-La and might never leave.

In fact, he thinks it’s all pretty swell, especially when he meets Wyatt’s Sondra, who bathes naked under waterfalls and has read all his books.

Well, at least Capra acknowledged that women can read, right?

Conway’s brother George, his direct foil, becomes increasingly angry and suspicious of the peaceful inhabitants of the valley, whose lives span hundreds of years.

Lost Horizon

Friday, Feb. 1, and Saturday, Feb. 2, at 7 and 9:30 p.m.

Sunday, Feb. 3, at 3 p.m.

$3 general admission; free for PSU students with ID

Conway’s speeches on the greed and violence of humanity would sound trite now but are forgivable here. At one point, Sondra, who has never seen the outside world, naively exclaims, “I wish the whole world could come to this valley!” Conway quickly tells her that if the whole world were in Shangri-La, it would no longer be a utopia. Even in 1937, world peace was a pipe dream.

Capra created Shangri-La by shooting on location in various places in California and Nevada and combining those shots with stock footage of the Himalayas.

When the American Film Institute restored the film in the 1970s, seven minutes of film were never recovered, so the audio for several scenes is accompanied by still pictures representing the intended action.

If you are at all interested in the history of film— specifically, the history of utopian societies in film—Lost Horizon is definitely a classic; it works both as a compelling adventure and a portrait of an imperfect world.