As part of Portland State of Mind, From Debt to Degree, a symposium seeking solutions to the student debt crisis, convened at the Smith Memorial Student Union Ballroom on Oct. 23rd.

Keynote speakers included Mark Kantrowitz, a nationally recognized authority on student financial aid, and Rohit Chopra, student loan ombudsman at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The symposium also gave voice to student experiences and concerns regarding debt. A panel convened between keynote speakers, and featured Rayleen McMillan, director of university affairs for the Associated Students of PSU; Deyalo Bennette, ASPSU senator; and Nina Nguyen, a student at Oregon State University and chief of staff for the Associated Students of OSU.

KGW news anchor Tracy Barry emceed the event and moderated the student panel. PSU President Wim Wiewel opened the discussion by laying bare the facts on the current debt crisis.

With over $837 billion in loans, the student debt crisis “’interferes with graduates’ abilities to buy homes and become [financially solvent],” Wiewel said, addressing a morning crowd of around 70 attendees.

According to Wiewel, the roots of the debt problem began with state budget cuts in the 1980s. “Twenty years ago, 56 percent of tuition was paid by the state,” Wiewel said, then observed that the state provides 11 percent of present-day tuition funding.

“We don’t spend any more on students now than we did 20 years ago. What has changed is who is paid,” he continued, indicating students are the ones making significantly larger payments on tuition.

Wiewel highlighted recently proposed student debt solutions, including the freeze of tuition increases to 2 percent and the creation of a task force to explore Pay It Forward, the state legislature’s proposed plan to allow Oregon students to pay for college after graduating.

“Students [are] scared by potential debt,” Wiewel said. ”That’s why we have to address this problem.”

Following an introduction from Barry Kantrowitz, a self-described “numbers person” cited several figures related to student debt while echoing Wiewel’s earlier statements.

“College affordability is still a problem,” Kantrowitz said, “[but] the burden of paying for college has shifted from the government and state to families.”

Kantrowitz asserted that the 2008 financial crisis stifled family incomes, leading students to rely more on loans to pay for higher education.

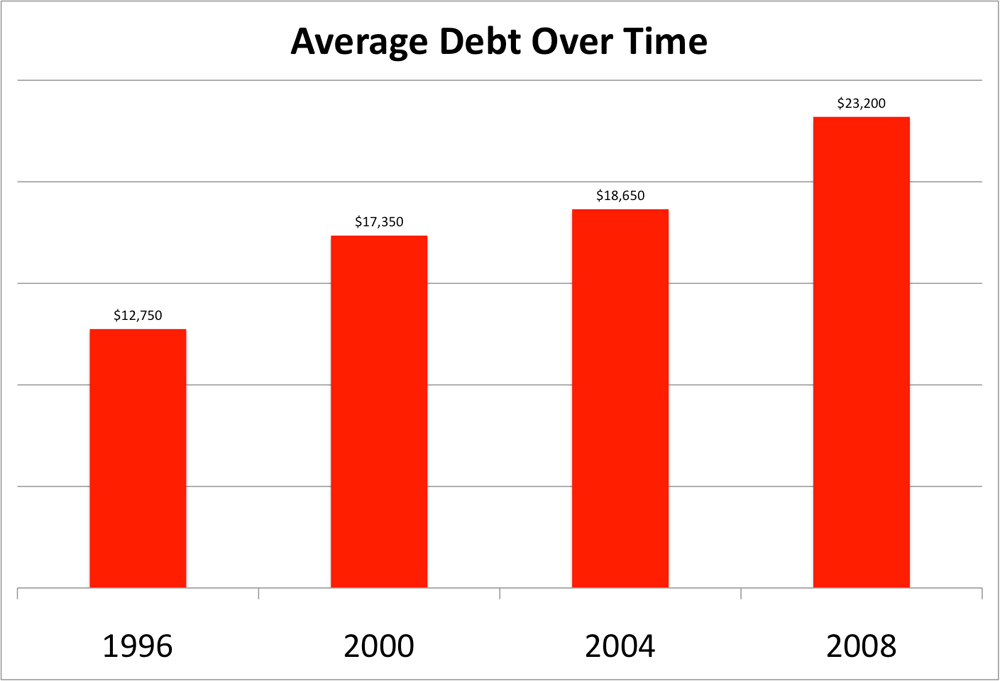

Other effects and trends noted by Kantrowitz included more students opting for Associate of Arts and certificate programs instead of longer and more expensive Bachelor of Arts programs, and a significant increase in debt-to-income ratios, changing from 1:3 to 1:2 between 1992 and 2008.

During that same time period, the percentage of students graduating with excessive debt also increased, rising from 2.3 percent to 12.4 percent

Acknowledging the reality of the current problem, Kantrowitz attempted to assuage financial fears with a proactive message.

“All this talk of us being in a student loan bubble is a little bit misleading. It’s not yet a bubble,” he said, “and the time to do something about it is now.”

Chopra took a tone sympathetic to student borrowers as he explored other debt crisis precursors and problems, at one point focusing on perceptions around the problem of loan payment delinquency.

“I’m really bothered by people saying ‘students are being irresponsible,’” he said. “They were thinking, very logically, before the crash [in 2008] that they would graduate and get a job.”

Relating results from CFPB surveys, Chopra explained that many graduates were often forced to work in jobs that did not match their skills and, thus, did not earn enough to make loan payments.

Chopra sought to further diffuse misconceptions of student borrowers. “The overwhelming theme from stories and anecdotes [heard by the CFPB],” he said, “is that borrowers want to pay, but they can’t find a plan that works for them,” later stipulating that “[The CFPB is] really thinking hard how to help the [millions] of students who already have the $1.2 trillion in student loan debt.”

Emphasizing a lack of a “one-size-fits-all” solution for the present crisis, Chopra said existing borrowers might benefit from income-based repayment options or restructuring private loans to increase affordability, while securing affordable tuition for future students will require finding a fix for college costs.

Compared to Kantrowitz and Chopra, the student panel’s perspective painted a less optimistic picture.

Both Bennette and Nguyen expressed problems with debt frequently forcing them to forgo daily necessities.

“Sometimes I have to starve myself,” said Nguyen, indicating that decisions such as “Am I going to eat tonight?” Or “Am I going to buy textbooks?” and other money-related fears routinely dominate her thoughts.

And although McMillan said she relies on a bar-tending job to help with costs, she admitted it only makes a small dent in her loan debt and that the time spent working sometimes puts a strain on her ability to take courses. Bennette and Nguyen both hold work-study positions, but neither credited their jobs with effecting a major difference in their bills.

Bennette indicated his debt as one of his “most scary and biggest stresses,” but finds that taking a new perspective helps reduce his fears.

“Fortunately, I’m a really good philosophy student,” Bennette said, explaining his ability to visualize his debt as intrinsically meaningless to him. “I can re-imagine my situation, [and] that’s why I don’t care about debt sometimes. I know that it’s something that’s not as valuable as my human worth.”

All of the students agreed that convincing future students to seek higher education without feeling discouraged by the threat of loan debt will be essential to the future of higher education.

“Teaching us the value of exploring knowledge,” said Benette, “at a younger age — that’s what helps people become entrepreneurs and start businesses. Instead, college is a factory model [that] puts people in a system instead of allowing them to create systems.”

The student panel also concurred on the importance of adding education on student loans to high school curricula.

Despite hard financial roads ahead, each student described sources of motivation that inspired them to stay hopeful, with family and community playing critical roles.

For McMillan, “the work that [ASPSU does] on campus with students” invigorates her, and enables her to “take negative energy and turn it into motivation.”

Nguyen also indicated supporting her community as motivational, with a focus on graduating and getting a good job to enable her to help her parents as one of her primary goals.

Bennette’s motivations offered the symposium another point of optimism.

“I know that I can’t give back without going through this process,” Bennette said. “We need to be on the right side of history and know that it’s better for our future, [that] it’s better for society in general that we educate each other. I do believe in this institution with confidence and pride to dream big, [but student debt] definitely does put barriers on my dreams, and I don’t think you should have to do that — I think you should be able to explore infinitely.”

But Bennette’s philosophical optimism was tempered with foreboding realism as well.

“I hope our energy [to find solutions] doesn’t get lost,” Bennette said, “because by the time my brother and sister get to higher ed, they’re going to be priced out.”