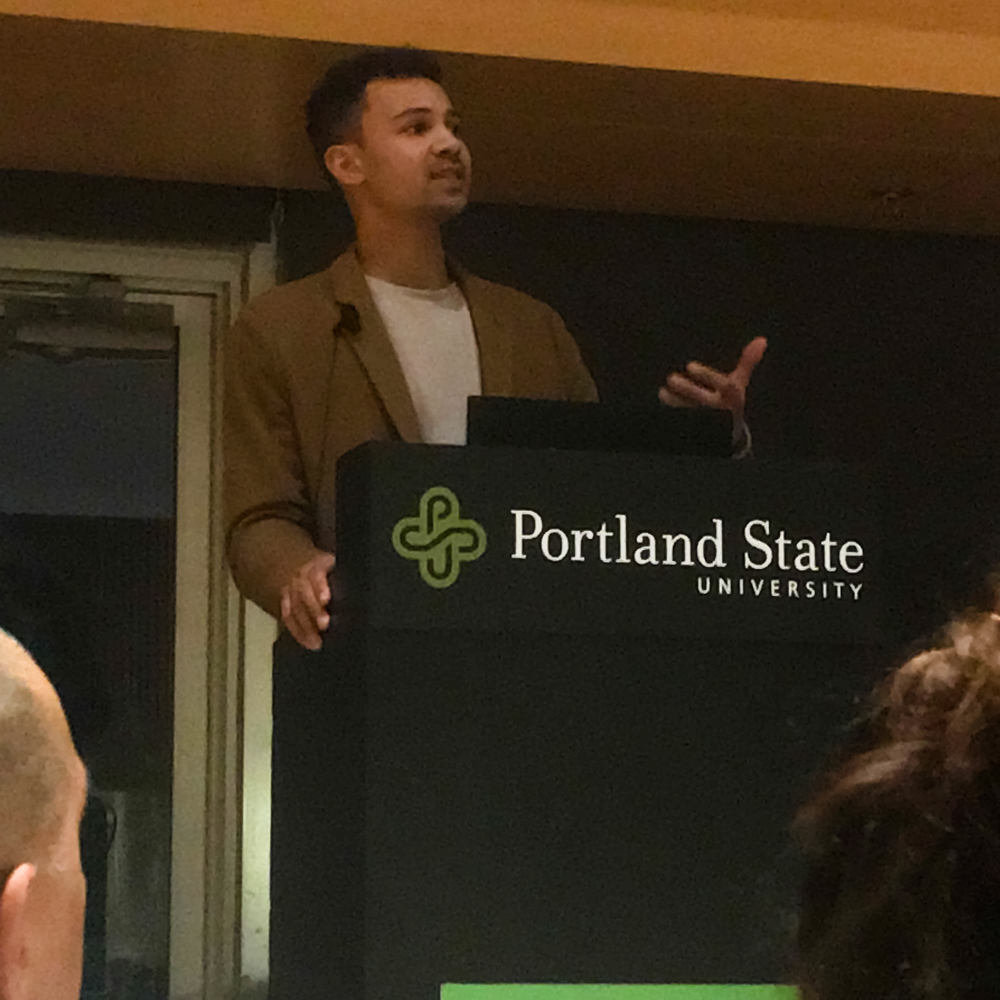

Sam Sinyangwe, a policy analyst and data scientist who works with communities of color to fight systemic racism through cutting-edge policies and strategies, gave a talk on Nov. 29 at the Smith Memorial Ballroom.

The event was hosted by Oregon Justice Resource Center, a statewide non-profit that works on criminal justice reform, sponsored by Portland State.

Sinyangwe uses his analytical and data mapping skills to advance the cause of racial justice, particularly with regard to police violence. His website mappingpoliceviolence.org provides data going back to 2013. He uses his data to advance solutions to police violence through Campaign Zero, a website he co-founded, which is updated continuously in response to the ideas and insights of activists, organizers and concerned citizens nationwide.

Sinyangwe framed his talk around the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown by Darren Wilson, a white police officer, in Ferguson, Mo. and the national public outrage which ensued after a grand jury decision not to indict Wilson. A year later, Ferguson’s police chief and city manager both resigned after a Department of Justice report found systemic racial discrimination by Ferguson police and its court system.

Sinyangwe said his data mapping and analysis arose with the need for validation of the lived experiences of communities of color. “When communities would tell the truth about their experiences—their lived experiences, experiences that transcended generations—you would hear from policy-makers and academics and data scientists a simple question of ‘Where is the data? Where is the data to validate your experience and your life?’”

Caitlyn Malik, a senior at PSU majoring in communications and a peer educator for Illuminate, PSU’s relationship and sexual violence prevention program, also attended the talk. She said she was shocked to learn how little data the federal government requires from police departments about police violence and that it had not been aggregated and presented to the public before Sinyangwe and his team did so.

“This is critical information the public needs to be aware of, especially with rising visibility around police violence in our country,” Malik said. “At the same time, it is unfortunate that ‘objective’ numerical data is what is believed most in our country, as opposed to personal testimonies that highlight long-standing patterns of violence affecting whole communities.”

When asked how this data might be used by the PSU community, Malik said she would like to see the critiques of policing applied to campus public safety officers.

“I would really like to see a critical re-evaluation of the policies and training that CPSO follows. I think the robust evidence Sam presented makes a strong case for us to critically re-evaluate what safety means for everyone on our campus.”

Bobbin Singh, executive director of Oregon Justice Resource Center, moderated a panel after the talk which included Sinyangwe and other criminal justice reformers. Singh, who referred to mass incarceration as “the civil rights issue of our time,” said the greatest indicator of a country’s value system is how it treats those on the margins and are accused or punished.

“[W]hen we look at our criminal justice system and how we treat those who we deem criminal or violating the social contract, I fundamentally believe that we’re a deeply broken society,” Singh said.

Another attendee, Lucinda Hites-Clabaugh, was wrongfully convicted in 2009 of sexually assaulting a student while working as a substitute teacher in Woodburn, Ore.

Hites-Clabaugh’s conviction was vacated in 2012 by the Oregon Court of Appeals on the basis the trial judge prejudicially erred in denying her expert to testify about deficiencies in the police interview of the alleged victim.

“I know what it feels like to be wrongfully convicted and I know the total shock you go through because you can’t believe that people would believe something horrible about you,” Hites-Clabaugh said. “In fact, all of my friends were in denial for a while too. They were all saying ‘Oh don’t worry about it Lucinda, you know, they’ll get it all straightened out.’ They all believed in the system.”

As an exoneree, Hites-Clabaugh has been attending international conferences held by Innocence Project, a non-profit organization that uses DNA evidence and criminal justice reform as tools to overturn and prevent wrongful convictions. Hites-Clabaugh said her focus has been on helping others who are wrongfully convicted.

In 2017, exonerations in the United States reached a record high for three years in a row, according to researchers at the National Registry of Exonerations. Racial disparities in the criminal justice system also make it more likely for people of color to end up behind bars and stay there longer.

Hites-Clabaugh pointed to prosecutors’ offices as a key area of the criminal justice system needing reform. “It’s fine if everybody follows the rules, you know, but the prosecutors don’t.”

Experts point to an increasing trend of accountability in prosecutorial officers as a partial explanation for the rising rate of exonerations. Hites-Clabaugh refused a plea bargain in her case, but 95 percent of the cases prosecutors decide to prosecute end with defendants pleading guilty before ever seeing a trial, judge or jury.

“The system would collapse if every case that was filed in the criminal justice system were to be set for trial,” said Texas Judge Caprice Cosper in a 2004 interview with PBS. “The system would just entirely collapse.”