While climate change continues to damage parts of the world, those displaced as a consequence do not meet the legal requirements to qualify for refugee status. In response to a growing number of displaced peoples as a result, 164 countries formally adopted the UN Global Compact for Migration on Dec. 10 and 11, 2018 in Marrakesh, which seeks to expand the definition of refugees.

In the 1951 Refugee Convention, the UN defines a refugee as “one who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

The new global compact took two years to create and ratify, making it the first global agreement to dictate a consistent approach to migration due to climate change. According to Public Radio International, Australia, United States and several EU countries abstained from signing on to the new definition.

Refugees Without Representation

According to the Overseas Development Institute’s 2017 report, ten of 2016’s largest events leading to displacement were in relation to natural disasters, with eight out of 10 located in East and Southeast Asia and some 13.5 million people displaced in all.

As reported by The Intercept, tens of thousands of residents in the U.S. were displaced due to natural events worsened by climate change in 2018, from the wildfires of California to the hurricanes of the eastern U.S.

Hurricane Florence left 53 dead and destroyed 2,000 residential properties while damaging over 70,000 more. According to a study by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Stony Brook University and the National Center for Atmospheric Research, effects from climate change caused the storm’s rainfall to be 50 percent higher than it would have been otherwise.

Summer 2018 was the fourth hottest in history for the U.S., as reported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, leading to intensified fires and delayed rainy seasons. In July 2018, the Mendocino Complex Fire burned over 450,000 acres in California, claiming the title of the largest wildfire in state history. By November, the Camp Fire of northern California became the deadliest after claiming 86 lives and displacing 50,000.

The Dry Corridor, a strip of land running through Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, typically has a dry season and a wet season which correspond to the U.S. winter and summer seasons, respectively. In the middle of the wet season is canícula—or dry season—which has continued to become longer and drier for the past 20 years. In poor farming areas where people make their living based on how many bags of beans they can produce, the extended drought is making life more and more difficult.

Chris Castro, a climate scientist at the University of Arizona, told The Intercept, “What’s scary is that we’re getting these drier and hotter midsummer droughts during years where natural climate variability would not otherwise suggest that should be happening.”

Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia along the Bay of Bengal, Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, who have already fled violent persecution and genocide in Myanmar, may again be displaced soon. According to December 2018 figures from the UN, over 900,000 Rohingya refugees have fled to neighboring Bangladesh. However, the sudden increase in numbers has led to an accelerated rate of deforestation. A June 2018 World Bank report claims that if greenhouse gas emissions from the region continue at its current pace Cox’s Bazar will become the most affected region by climate change in all of South Asia by 2050.

Economics of Denial

The National Flood Insurance Program is a program run by FEMA to provide coverage at cheaper rates for areas that are prone to flooding. However, with increased flood rates, the costs of running NFIP have increased over the last few years. Currently, NFIP is over $20 billion in debt, yet continues to operate.

As part of their ongoing coverage of climate change, VICE News went to Miami, Fla. to look at the possible cost of climate change, meeting with the Chief Property Underwriter for Swiss RE, an insurance company based in Switzerland. According to Monica Ningen, the risk assessment for a three-foot rise in sea level—projected to culminate by 2100—would amount to $145 billion in property damage and 300,000 homes destroyed.

Additionally, Swiss RE calculated losses from natural disasters in 2017 to be $330 billion, with insurance companies covering less than half of the cost. “Extreme weather events, heightened by climate change, coupled with the fact that many new homes are built on flood-prone land, is making the problem worse,” as stated in their report on mitigating climate risk.

Swiss RE, is not alone. Insurance companies across the board are paying attention to the havoc climate change is causing on a global scale. However, while Forbes has noted they’ll be one of the hardest hit institutions, little is being done to mitigate effects. The Asset Owners Disclosure Project—which researches and rates various financial institutions—reported in May 2018 that “Less than 0.5 percent of assets invested by the world’s 80 largest insurers are in low-carbon investments that provide solutions to climate change, despite the insurance sector being highly exposed to its financial risks.”

Politics of Denial

Since the Industrial Revolution, the planet has warmed more than one degree Celsius. If it is to warm past two degrees, the tropical reefs will die, the Persian Gulf will become uninhabitable and sea level will rise several meters. According to the UN Ocean Conference of 2017, more than 600 million people—around 10 percent of the global human population—live within 10 meters of coastline, and 97 percent of fishermen live in developing countries. As ice sheets from Greenland and Antarctica continue to melt, sea level is expected to rise 15 meters by 2500.

James Hansen, a leading climate scientist, called this progression “a prescription for long-term disaster” in the August 2018 New York Times Magazine special edition covering human failure to combat climate change. Nearly everything scientists understand about global warming was known in 1979, having collected data since 1957 upon observations from as early as the 1800s. In the late ‘70s through the ‘80s, leading climate scientists worked to educate governments and leaders about the effects of greenhouse gases on Earth’s atmosphere.

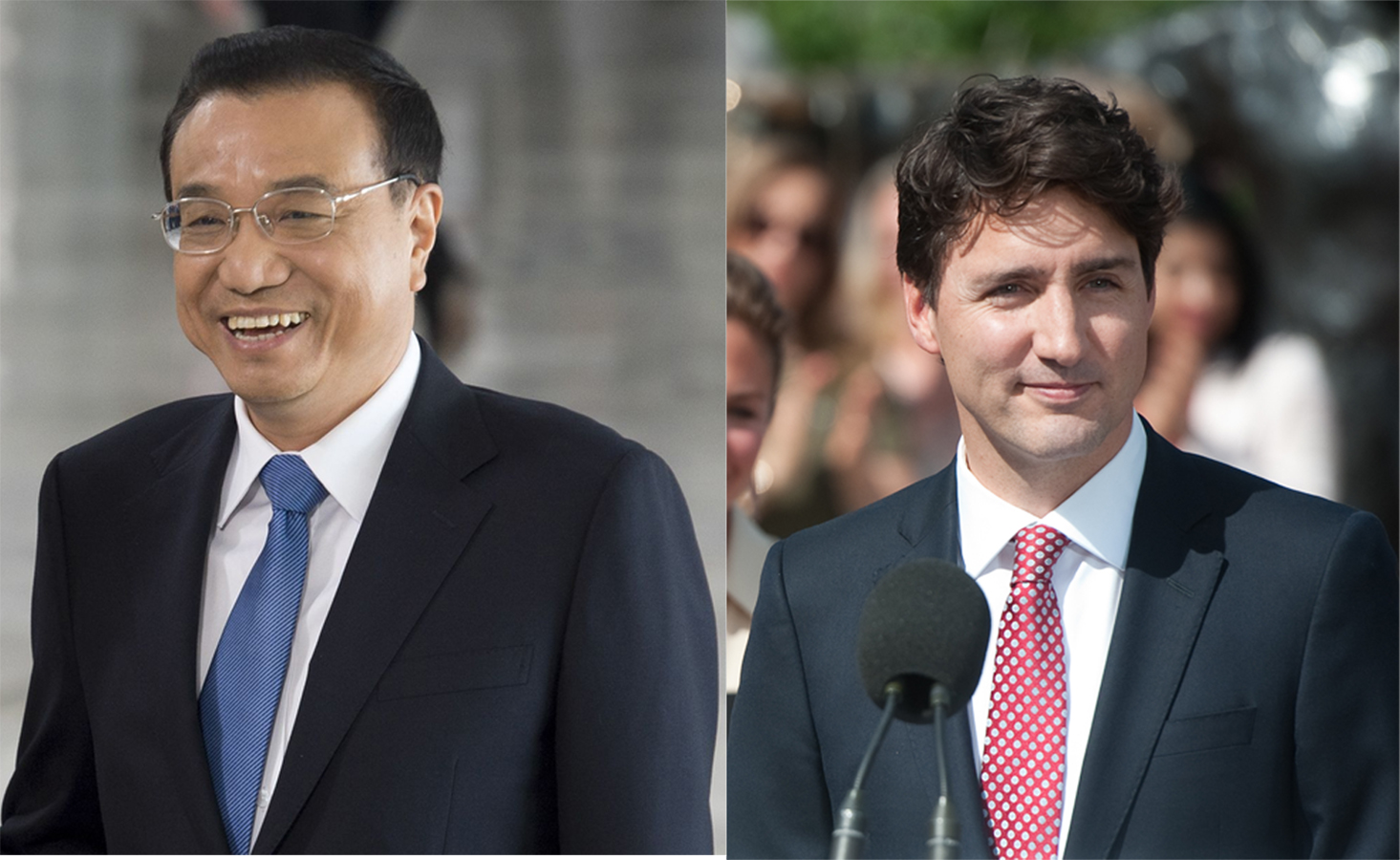

The Paris Agreement, a non-binding agreement ensuring international cooperation to combat human effects on climate change, was signed on April 22, 2016. The U.S. and China—the two largest consumers of energy—were originally parties to the agreement. However in 2017, President Donald Trump withdrew, claiming the U.S. paid unfair dues to other nations. According to Scientific America, the U.S., with less than five percent of the world’s population, uses around a quarter of the world’s energy. Additionally, one of the original conditions to the Paris Agreement is to assist developing nations as they tend to need additional assistance due to disadvantage in resources and socioeconomic institutions.

Bleak Projections

In their March 2018 report, “Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration,” the World Bank Group projects more than 143 million people displaced within their own countries due to climate change by 2050, stating, “Internal climate migrants are rapidly becoming the human face of climate change.” Focusing on Latin America, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, the report notes four main driving factors of climate displacement: extreme heat, lack of freshwater resources, rising sea levels and extreme events.

In essence, if the projections are correct, internally displaced persons will be more likely to run from damages caused by climate change within the next 30 years than from war and political disorder.